Climate change threatens ice sheets and ecosystems, but it also threatens human cultures.

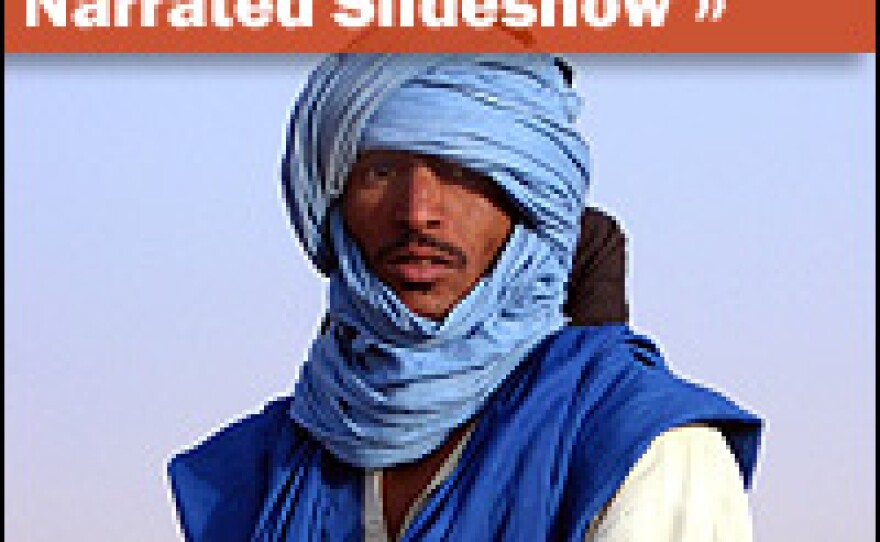

For centuries, the Tuareg people have lived as nomads, herding their animals from field to field just south of the Sahara Desert in Mali, near Timbuktu.

"Our life is basically the animals we have, so we protect them and we feed them," says Mohamed Ag Mustafa, a herder living the traditional nomadic lifestyle. "Whenever we need tea or grain or clothes, we take an animal to the market and sell it and buy something."

But this way of life has become impossible due to a change in the climate.

Over the past 40 years, persistent drought has forced the Tuareg to give up their wandering way of life. To survive they have had to start settling in villages and cultivating land to secure a food supply which is less susceptible to drought.

Preserving Culture

CARE is an international humanitarian organization working to alleviate poverty. Uwe Korus, director of programs for CARE in Mali, visits the town of Er-Intedjeft near Timbuktu, where he is greeted warmly. He is here to learn what the Tuareg need in order to make the rapid and jarring transition to a new way of life. One of the big questions on Korus' mind is whether the Tuareg can retain their ancient culture.

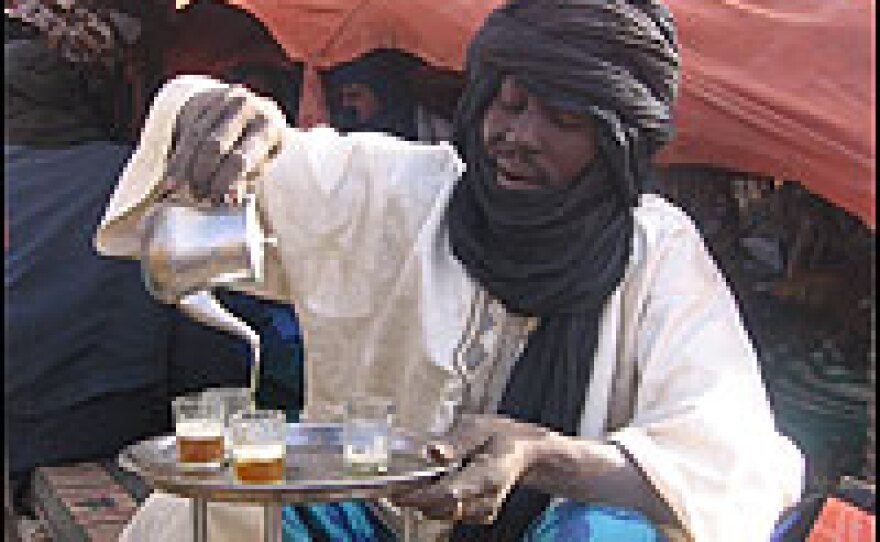

The Tuareg welcome Korus with a mishwee, a traditional feast like they used to have in the desert. They build a fire in a sand pit, and when the sand gets scorching hot, they bury a sheep carcass in it. After the sheep has roasted, they blow off sand still clinging it and bring it over to straw mats laid out under rust-colored tents they erected for their guests.

As the women look on, the men of the village sit around the main dish along with Korus and the others from CARE. After the men are through eating, the bones are cleared away for the children and women to pick over, and the Tuareg sit down and talk for hours. They tell the people from CARE about their struggle to settle down. The nomads say they need to learn to farm, they need clean water, health care and veterinary care for their animals.

Welcoming Change

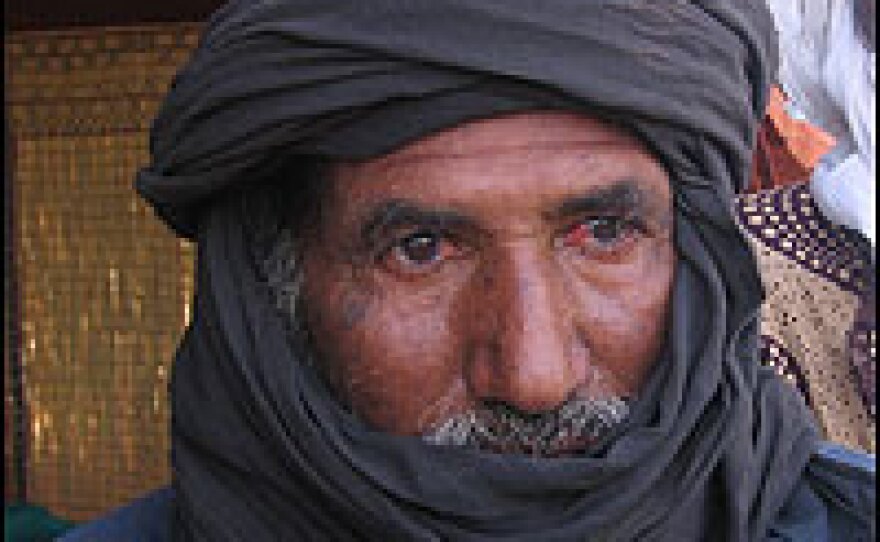

Mohammad Ag Mata, the chief of Er-Intedjeft , is in his mid-60s and appears frail. He is resolute about his decision to give up his nomadic ways.

Mohammad Ag Mata says droughts are responsible for the shift in the Tuareg lifestyle. He used to have 200 head of cattle, but they all died in droughts in the 1970s and '80s. "If it hadn't been for a little money I stole from my father and saved, we would have starved," he says.

Jacob Aromar also lives in Er-Intedjeft. Aromar is not a herder like his forefathers, but a school teacher. He points out the changes taking place all around him, such as the Tuareg homes which used to be tents, but are now built with mud bricks they make by the river.

The Tuareg diet has changed from one of meat and cheese to one with more grains and vegetables, and they still have a lot to learn about growing crops. A pump was donated so the town can draw water from the nearby Niger River and irrigate tomatoes, rice and potatoes. However the pump is not working because no one has been trained to use it.

Social Change

Hadijatou, a Tuareg woman in her mid-20s, rises early to sift millet and prepare breakfast. Her parents had been nomads, but she is grateful she is not.

"Before, everything was given to us by the men. When you are given what you need by other people, you are dependent on them," says Hadijatou. "But when you are producing what you need you depend on nobody. The life now is far better."

Traditionally, the men don't care what the women think. Children don't count for much, either. Mohamed Ag Mustafa, the herder still living the traditional Tuareg lifestyle, says he sees no reason to send his children to school: "Maybe school is useful for people in the cities, but not for us. As far as we are concerned, children are only useful for getting water or keeping an eye on the cattle."

Mustafa also describes how life is getting harder year by year. The area is getting drier, so it's more difficult to find grazing for their animals. A yellow dusty wind is blowing south from the Sahara.

Ultimately the Tuareg may have no choice; this may be the end of a culture.

"This is a very rapid development induced by changes in their climatic, political, economic environment," says CARE's Uwe Korus.

Nevertheless, Korus is hopeful.

"The Tuareg are powerful people," he says. "I think they will adapt."

It's evident they will need a lot of help on that journey.

Produced by Jane Greenhalgh

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))