In English, you might call what's happening to Mexico's economy a "perfect storm."

In Spanish, they say llueve sobre mojado, or "it's raining on wet ground."

In either language, the effects of the global economic recession are devastating in Mexico, the world's 13th largest economy.

The crisis has hit many nations hard, but Mexico's problems are compounded by factors that leave it facing its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

All of its legal sources of revenue — mainly tourism, oil exports and remittances from the United States — are in decline. As a consequence, Mexico's economy may shrink by more than 6 percent this year, according to the Bank of Mexico.

Oil production is tumbling. Remittances from migrants living and working — or now out of work — in the United States have fallen. The spread of swine flu and Mexico's drug war have crippled the country's tourism industry.

And manufacturing activity is weak, as evidenced by the automotive industry where production is expected to slide 40 percent this year.

Only the multibillion-dollar trade in illegal narcotics seems to be thriving, despite the Mexican army's efforts to put the cartels out of business.

'A Very Difficult Moment'

"It's really a very difficult moment for the Mexican economy," says Manuel Galvan, an economist with Metanalisis, a private research firm in Mexico City.

In recent years, Mexico's economic growth has been driven primarily by international trade. And under the North American Free Trade Agreement, Mexico married its economy — for better or worse — to the market in the United States.

Last year, almost 85 percent of all Mexican exports were shipped north of the border. When the U.S. economy started to stall, the effects were amplified in Mexico, Galvan says.

"Mexico has a very weak internal demand," Galvan says. "So that is the main reason why we are seeing a deeper recession in Mexico than in the United States."

Unemployment Soars

Mexico's official unemployment rate has nearly doubled in the last year. This statistic however only gauges formal private sector jobs and grossly underestimates the number of people out of work.

Mauricio Guerrero runs a Mexico City-based company called CIACSA which makes industrial air compressors. In good times, he says he has 200 people working for him.

"Now in this moment we need to reduce this plant. We are only 14 people working in this moment," he says. Guerrero's firm specializes in making compressors for oil rigs and refineries. Business has fallen along with petroleum prices.

Guerrero says that when the U.S. banking crisis unfolded, credit also dried up in Mexico. He says he had to mortgage his home and take out advances on credit cards just to make payroll.

The interest rates on some of these loans can be up to 35 percent, he says.

"Every week we need to pay the people and every month we need to pay the loans for the banks and this is the worst part of the history, because now we have new projects but we are working for the banks," he said.

Hitting Bottom

The only good news is that most economists say that Mexico has hit the bottom of the crisis and the recovery could start at the end of this year or early in 2010.

Meanwhile, the effects of the crisis are spreading across the economy and the country.

Mexican hotels, restaurants and tour operators shut down almost entirely in May because of the swine flu outbreak. That health crisis is over, but now tourists are hesitant to spend money.

In rural Mexico, villages depend heavily on cash sent home by Mexicans working in the United States. But those remittances dropped 20 percent, according to the latest figures available from the Mexican central bank.

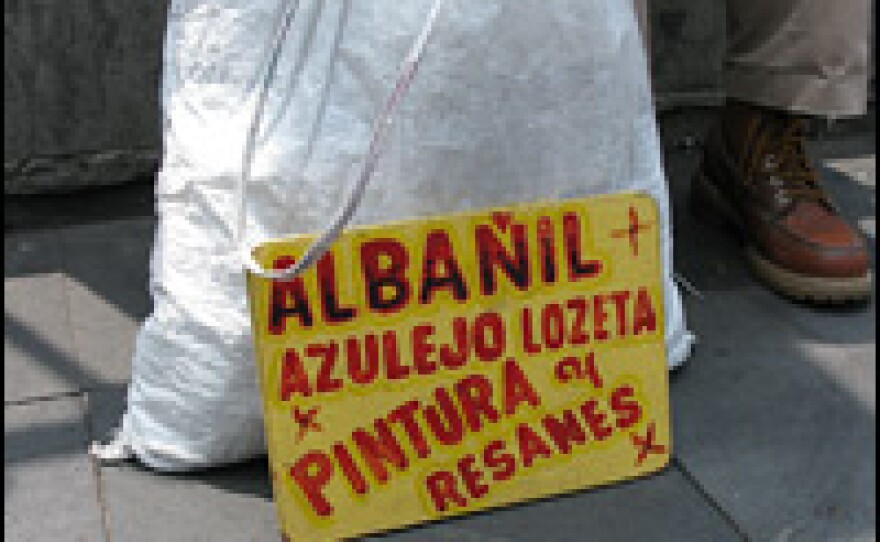

In downtown Mexico City on a recent day, constructions workers sat in a long line outside the main cathedral waiting for jobs that pay $10 to $15 a day. Small signs at their feet say plumber, electrician, and builder.

Venustiano Martinez Fonseca comes here most mornings to try to get work but he says there is no work. He says the last time he was hired was a month and a half ago and that job only lasted two days.

"At times when I leave here," he said, "I go and sell things in the markets to get money to survive."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))