Larry Peterson spent more than 17 years in prison for murder and rape before DNA testing led a judge to overturn his conviction.

The legal victory ended one phase of Peterson's life. But it also marked the beginning of a new battle: Even though the state agrees that Peterson is no longer guilty of the crime, the burden now falls on him to prove that he is innocent of the charges, which he must do in order to receive compensation for the years he spent in prison.

"My life has not always been an honorable life," the 56-year-old New Jersey man says. "[B]ut I have never been a murderer, never been a rapist."

For the past two years, Robert Siegel has followed Peterson's long and difficult journey from incarceration to vindication. This is the story of Peterson's efforts to rebuild his life, and of his continuing fight to seek redress for the years he lost in prison. It also seeks to show how Peterson's exoneration has affected the family of the victim of the crime that originally put him behind bars.

The Crime

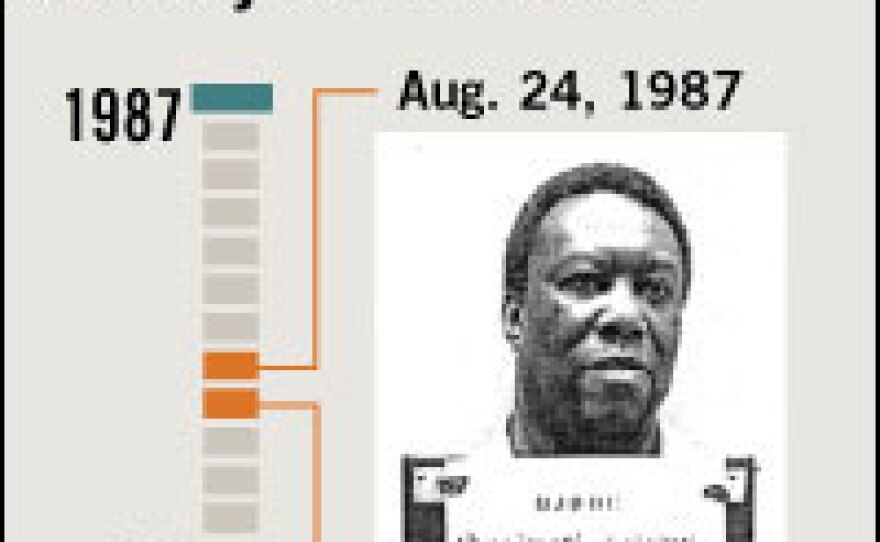

The story of Peterson's fight with the state of New Jersey began in the early hours of Aug. 24, 1987. That's when the body of 25-year-old Jacqueline Harrison was found in a field in Pemberton, N.J. The mother of two had been brutally raped and strangled; a stick had been shoved down her throat. The crime appeared to have occurred after a night of partying: Police found evidence of crack cocaine in her system and of sex with more than one man.

Patricia Harrison recalls that her sister's life was reduced to news accounts of a broken corpse in the woods and a reckless weekend.

"All they read and believe... is what was printed in that paper, and it's a shame. It's a crime," she says.

That August, Larry Peterson lived at his mother's house — not far from where Harrison's body was found. Peterson, then 36, was a divorced father of three who had a problem with alcohol and drugs, and a criminal record for petty crimes.

"I became involved with the wrong people. I abused various substances and just fell into a rut," Peterson remembers. "Alcohol. Drugs. Nightlife. Riotous living. That was my downfall."

In those days, he says, he made his living in the woods, collecting and coiling vines that stores sell as ornamental wreaths.

That could account for the fresh scratch marks that a neighbor saw on Peterson's arms after Harrison's murder. But to the neighbor, the scratches were signs of a recent struggle. She notified police, who quickly focused on Peterson.

Police questioned Peterson, who denied any involvement in the crime. But three weeks later, Peterson was arrested and charged with capital murder and aggravated sexual assault.

The Trial

Peterson sat in jail for 17 months, until his trial began in February 1989.

At the heart of the prosecution's case was forensic evidence that seemed strong by the standards of the time.

Gail Tighe, a forensic scientist at the New Jersey State Police crime laboratory, testified about pieces of hair that were found on the victim's body and on the stick with which she was assaulted.

Tighe said those bits of hair and samples of Larry Peterson's hair had been examined under a microscope and that they "compared" — meaning they "fit the same criteria, fit into the [same] range."

The case against Peterson also included testimony by his friend Robert Elder. He testified that during a ride to work together on the morning of Harrison's murder, Peterson used graphic language to describe how he raped and killed her. Two men in the front seat of the car also testified that they overheard Peterson talk about the crime.

The case against Peterson sounded strong — even to him.

"If I was sitting on the jury, I would be inclined to convict the person also," Peterson says of his trial.

And to the relief of Patricia Harrison, the jury did convict.

"We were at peace in that the case was closed. Her murderer was not walking the streets. It was documented guilty," Harrison says.

Search for Vindication

Peterson was convicted of felony murder and aggravated sexual assault; he was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

From Trenton State Prison, Peterson appealed his conviction and lost. But he kept trying to prove his innocence.

By 2005, with the help of the Innocence Project — a nonprofit litigation and public policy group that works to overturn wrongful imprisonments — Peterson had won the right to DNA testing of the hair evidence from his trial.

The DNA tests showed that the hairs from Peterson's trial belonged not to him but to the victim, Jacqueline Harrison. What's more, the tests also turned up the tissue and semen of an unidentified man — a "Mr. X" whose DNA, so far, has not turned up in any criminal database.

The prosecution fought for and won additional DNA tests on hair that had been collected at the crime scene but never used in court. Those additional DNA tests yielded the same results as the first round: There was no DNA evidence linking Peterson to the crime.

DNA Results

In July 2005, six months after the first DNA results were released, Judge Thomas Smith vacated Peterson's 1989 conviction, which meant that in the eyes of the law, Larry Peterson was no longer guilty of the crime.

As Judge Thomas Smith told the courtroom: "The strength of the [state's case] is different at this point. We've got substantial biological evidence that would tend to indicate that, in fact, Mr. Peterson was not involved in the offense. I acknowledge that; anybody looking at the evidence would acknowledge that. But that does not mean that there cannot be a conviction in this case."

And the prosecution did, indeed, intend to retry Peterson for the same offense. They immediately re-arrested him and moved him from state prison to county jail.

Burlington County Prosecutor Robert Bernardi, who had taken office during the 1990s, told reporters that the case was weaker but that it was certainly "not an untriable case." Without the physical evidence, the prosecutor would build his case on witness testimony.

For Vanessa Potkin, an attorney with the Innocence Project, retrying Peterson was "unconscionable" and "ludicrous" in the face of the DNA evidence.

It took Peterson's mother a month to raise $20,000 to post bail. But on Aug. 27, 2005, almost 18 years after he was first taken into custody, Larry Peterson walked out of jail.

His happiness was short-lived, however. Peterson was out of work, his mother was in debt, and above all, he was now awaiting another trial for the rape and murder of Jacqueline Harrison.

This story was produced by Julia Buckley.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))