The lawn in front of Garfield High School in East Los Angeles was sodden from the morning's rain. But the weather didn't dampen the enthusiasm of many Garfield graduates, who came from all over Los Angeles and beyond to show their support for their former teacher, Jaime Escalante.

Escalante's former students recently learned he is in the end stages of bladder cancer that has spread throughout his body. The medical costs have depleted Escalante's savings, and the students are determined to help out.

'Barrio Kids'

To the astonishment of the outside world, Escalante taught many of these returning graduates math — advanced math, like trigonometry and calculus.

Garfield educates some of Los Angeles' poorest students, many of them from immigrant families, and many of whom never conceived of college as a possibility. But Escalante did.

The Bolivian-born teacher believed math was the portal to any success his students could achieve later in life. So before school formally began, and after school ended, his door was open for extra help. And the students came on weekends and worked through holidays to prepare for the hardest exam of all — the Advanced Placement calculus exam.

"It was hard," says Mark Baca, who now works with a Los Angeles nonprofit. "But he changed the minds of people all over the world about barrio kids."

Escalante's barrio kids became stars, exemplars of what can happen when knowledge-thirsty kids with ganas — a deep desire — to succeed combine with a dedicated teacher with ganas for their success.

"Everything we are, we owe to him," says Sandra Munoz, an attorney who specializes in workers' rights and immigration cases in East Los Angeles. She was not originally an Escalante student.

"But that's what he'd do," she says. "He'd see someone and decide they needed to be in his class. So he pulled me out my sophomore year and put me in his class, and I took math with him. He would teach anybody who wanted to learn — they didn't have to be designated gifted and talented by the school."

Munoz's cousin also ended up an Escalante student, and he was still learning English.

After-Hours Tutoring

Escalante tutored his students until late at night, piled them into his minivan and brought them home to their parents, who trusted Escalante in ways they never would other teachers.

"My mother used to stay up," says Arícelí Lerma, an attorney. "Not to check up on him, but to bring him a plate of food because she knew how hard he was working!"

He would teach anybody who wanted to learn -- they didn't have to be designated gifted and talented by the school.

Escalante, whose students mischievously nicknamed him "Kimo" (a play on The Lone Ranger's Kemosabe moniker), would not only work with his students until they were all ready to drop from exhaustion, he employed them in the summers as tutors. And he showed them that the best colleges in the country were not beyond their reach.

Lerma reels off a partial list of where she and other Escalante students from the class of 1991 went: Occidental, Harvard, Stanford, Dartmouth, MIT, Wellesley.

Dolores Arredondo, who is now a bank vice president went to Wellesley. She said that one year, Escalante appeared at the Pachanga celebration for Latino students that the Ivy League and Seven Sisters colleges held on the East Coast. It was a home-style Thanksgiving for those who couldn't afford to fly home.

"Someone told me they'd asked Mr. Escalante to speak, and he did," Arredondo says. "Not only did he come, he came with a suitcase full of tamales made in East L.A." A thoughtful taste of home for students who hadn't been there in a while.

Giving Back To 'Kimo'

Now, even though he hasn't asked for it, Escalante is getting his old students' help.

Actor Edward James Olmos, who received an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of Escalante in the 1988 hit movie Stand and Deliver, is spearheading an effort to support Escalante and his family in what looks to be the teacher's final days.

"Yes, he's dying," Olmos says. "We all will, eventually. But what we want is to die in comfort and dignity, with our loved ones around us. After all that Kimo has done for us, it's the least we can do."

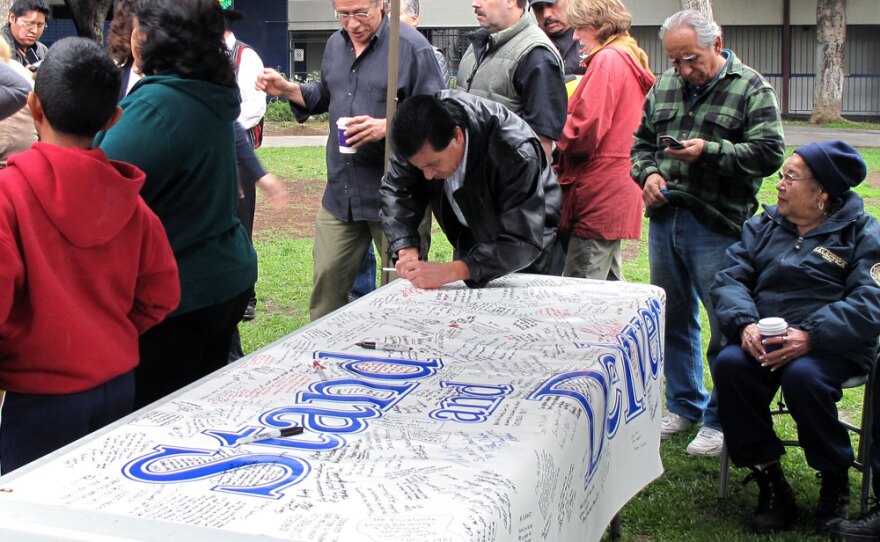

Back at Garfield, more people stream onto the school's lawn to sign a big banner that will be sent to Escalante. He is staying with his son, Jaime Jr., in Sacramento, Calif., so he can commute to Reno, Nev., for medical treatment.

As a Bolivian band plays in homage to Escalante's birth country, some people write checks or contribute cash. And drivers and passers-by stuff money into buckets shaken by two Garfield mascots — 6-foot felt bulldogs.

At the end of the day, the former students have raised almost $17,000, a sign that Escalante's kids and the community he made so proud were ready to stand and deliver for him.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))