One of the greatest rivalries in sports — and the oldest rivalry in the National Football League — will be renewed Sunday at Chicago's Soldier Field when the Chicago Bears host the Green Bay Packers in the NFC championship game.

"It doesn't get any better than to see the Bears and the Packers battling it out for a chance to go to the Super Bowl," says Bears coach Lovie Smith.

The two charter NFL franchises have pummeled each other 181 times since 1921, in some of the hardest-fought football games ever played. But it's been almost 70 years since they've met in a game that means as much as this one.

The 'Greatest Rivalry' In Football

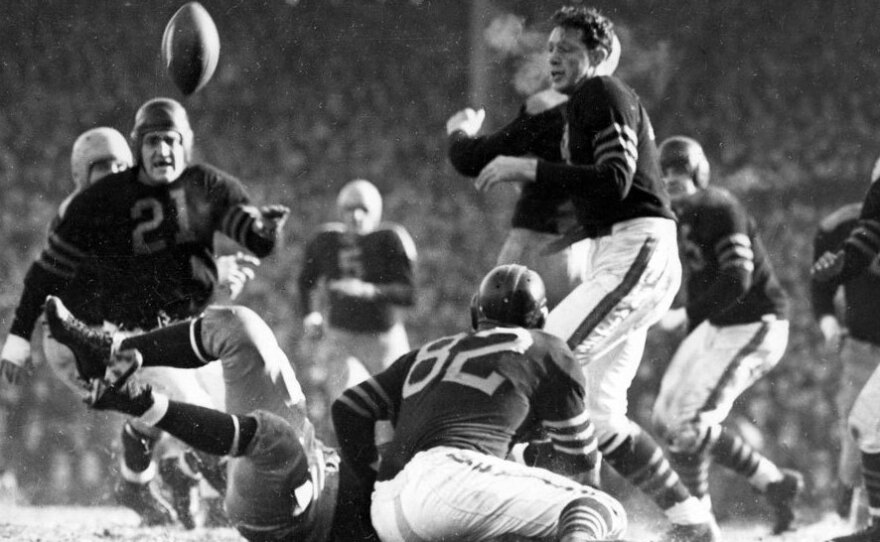

The last time the Bears and the Packers faced off in the playoffs was Dec. 14, 1941, at Chicago's Wrigley Field. (The legendary baseball park was also the home of the football Bears until 1970.)

"I remember the game," says Elmer Possin, 95, of Madison, Wis. "The Packers won the championship in '39 [the Bears won it in '40] and in '41 they both had good teams."

Possin says he's been a Packers fan since 1927, when his family bought its first radio. He attended his first game in 1933, and he's been a season-ticket holder for 60 years.

By the time of that 1941 game, the Packers-Bears rivalry was already well established. And the teams from neighboring states entered that Western Division playoff game with identical 10-1 records — their only losses were to each other.

Possin didn't go to the game in Chicago, but he remembers listening to it on the radio, and he remembers that the week before, football games across the country had been interrupted by the stunning news that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor.

"And as a result of Pearl Harbor, everybody that was living, I don't care how old or how young or what their station in life was, they did at least a 5- to 180-degree turn on their lifestyle," Possin says. "So winning or playing that game was not that important. You can see why."

Possin recalls that the the Bears kept the Packers' star, future Hall of Famer Don Hutson, out of the end zone. And the Chicagoans, despite a fumbled opening kickoff, crushed their rivals 33-14.

And despite Pearl Harbor, the game was a sellout, with nearly 45,000 fans.

"The Packers and the Bears always drew a full house," Possin says. In contrast, the next week at Wrigley Field, when the Bears beat the New York Giants 37-9 for the league title, a mere 13,000 fans showed up.

"It's the greatest rivalry in football," says Possin, who admitted that fans of the two teams have developed a certain animosity toward one another. But he stops short of calling it hate.

"Not in that way," says Possin. "We may say we hate 'em, but we don't mean it in that light. We respect them. It's a respectful hate."

'The Word Is Respect'

Another person who can't use the word "hate" is former Bears linebacker Doug Buffone. He played 14 seasons from 1966 to 1979 — and he faced the Packers more times than any other Bear.

"Everybody says, 'Doug, you must have hated the Packers.' I didn't hate the Packers. I mean, I loved playing against the Packers. It was like, whoever was left standing won the damn game," he says.

After the season, Buffone says he and teammates Dick Butkus, Ed O'Bradovich, Gale Sayers and Mike Ditka, among others, were all good friends with Packers greats such as Bart Starr, Paul Hornung and Ray Nitschke.

"The word is respect," he said, "and that's what we have for each other."

But during the season, Buffone says, the intensity of Packers-Bears games was unmatched.

"We didn't take any prisoners. On the field, it was do or die."

And off the field, Buffone says, the fans take the rivalry to another level, too.

"I can remember the night before at the hotel, 3 o'clock in the morning, guys coming through with trombones, hitting the fire alarms and waking us all up," he says. "These people really wanted to get us all agitated and aggravated, don't get any sleep, and that's just who they were.

"And I liked it, I really did."

'Packer Panic'

As for the practices leading up to the games, Buffone says, "We used to call it 'Packer Panic' week. ... Everything was faster, quicker; we gotta have this football game. That came right from George Halas."

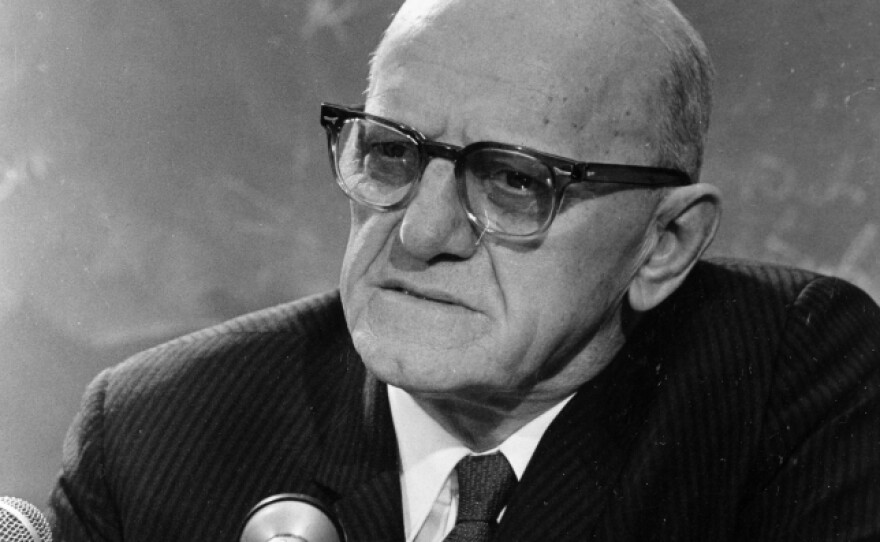

Halas was the founder, owner and longtime coach of the Bears, and Buffone and others say he helped build both the bitter rivalry and the foundation of respect between the two teams, along with Packers founder, player and coach Earl "Curly" Lambeau.

Some credit Halas with helping save his rival Packers in the 1950s when he went to Green Bay and played up the rivalry to help drum up taxpayer support for a new stadium.

And in 1958, when Green Bay was searching for a new coach, it was Halas who recommended Vince Lombardi. When the Bears won the NFL championship in 1963, the Packers hosted a dinner to congratulate Halas.

The only time the rivalry really turned vicious and nasty was in the 1980s, when the Bears were a dominant team and the Packers far from it, and on several occasions, Packer players took cheap shots at Bears players.

Party Like It's 1941

One of the reasons the Bears and Packers have met so infrequently in the playoffs is that they're in the same division. And in recent decades, the Packers have been good when the Bears were bad, and vice versa.

Now the two teams will square off Sunday for the NFC championship. The winner takes home the Halas Trophy, named for the Bears legend, and advances to the Super Bowl. The prize there? The Lombardi Trophy, named for the Packer great.

And fans on both sides of the Illinois-Wisconsin border, known as "The Cheddar Curtain," are stoked.

"It's probably the most important game," the two teams have ever played, says Chicagoan Vladimir Zintchenko, 24, a guitar teacher.

"Both teams have a lot in common, you know," he says. "They've both got the blue-collar winter background going on. Both play good in the snow. Both got the gritty fan base rootin' for them, die-hard fan base, and that's what makes it such a nice matchup."

Zintchenko says he'll be watching Sunday's game at Murphy's Bleacher Bar, across the street from Wrigley Field, where the last playoff game between these two teams was played.

In a tribute to that game, the sign outside of Murphy's reads: "Party like it's 1941."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))