D-Day soldiers landing on Omaha Beach. A naked Vietnamese girl running from napalm. A Spanish loyalist, collapsing to the ground in death. These images of war, and some 300 others, are on view at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in an exhibition called WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath. Pictures from the mid-19th century to today, taken by commercial photographers, military photographers, amateurs and artists capture 165 years of conflict.

One of the best-known war pictures of all time was taken by AP photographer Joe Rosenthal in 1945. Five Marines and a Navy corpsman, raising the American flag on Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima.

"It's such an important and historic photograph, but I don't know who any of those guys are," says documentary photographer Louie Palu — who found inspiration in the iconic Rosenthal image. "I wanted to meet the guys in that photograph. I wanted to know the name, the age, how young or how old they looked. I didn't want it to be an anonymous set of people raising a flag."

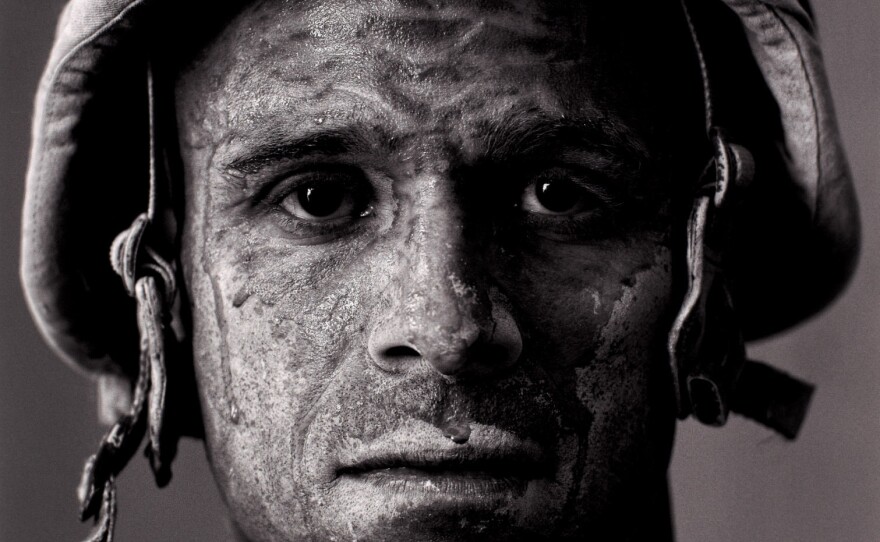

So when Palu was embedded with troops in Afghanistan's Helmand province in 2008, he made close-up portraits of the men. One of Palu's portraits became the signature image of this war photography show:

It shows 31-year-old U.S. Marine Gunnery Sgt. Carlos "OJ" Orjuela. His face, under his helmet, is caked with mud and sweat and exhaustion. He'd served in Iraq and then Afghanistan. His eyes look as if they have seen everything, and tomorrow they'll have to see some more. His face says "I want to go home," Palu says.

At the Corcoran, wall after wall, photo after photo — black and white, color, by men and women famous and unknown. In this day of the moving image — on movie screens, TV screens, smartphones — curator Anne Tucker says still pictures like these remain for a reason.

"Still photographs log into our brains differently than moving pictures," says Tucker, who originated the show at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. "And therefore they still have power and they still connect with us."

They're frozen moments. Not ever-changing blinks. They make us stop and look.

You can't take your eyes off the beautiful young soldier with the chiseled cheeks and dirty clothes in a photograph taken in Vietnam in 1971. Resting for a moment, the man sits on the broken track of an armored personnel carrier he's repairing. With long, soiled fingers he holds a clipping from some weekly livestock report. He stares into space. Photojournalist David Burnett took this picture.

"He almost has what they used to call the thousand-yard stare," Burnett says. "He's thinking. I don't know what he's thinking. He's reading a letter from home and it's just a picture that kind of captures him in this moment of pondering what the rest of his life was like when he wasn't being a combat soldier."

Burnett didn't know right away what a powerful image he'd gotten: "My film went into an envelope, was sent to Saigon, was put on a plane, it went to New York, it was developed, it was edited, and the first I even saw the picture was about 10 days later when Time magazine published the photograph."

Burnett didn't get the soldier's name, or age, or hometown, and he regrets that.

"Every time I walk into a diner now and I'll see a couple of Vietnam vets sitting around talking I'll just wonder, could this be the guy from my picture? I would love to be able to find him before one of us passes away," he says.

Burnett and the young tank repairman made an anonymous passage through one another's lives. And yet that soldier haunts the photographer.

"Now, 42 years later — just to go have a cup of coffee with this guy — I'd love to do that," Burnett says.

What's the purpose of these pictures? Image after image of men, mostly, at war, carrying guns, under fire, running from — or toward — danger. Killing, being killed.

"We need to tell the public, the public of the entire world what war is really like," says photo editor John Morris. During World War II, Morris ran Life magazine's London office. He was photographer Robert Capa's editor, and later the picture editor at The New York Times and the Washington Post. Morris says the public doesn't get to see everything — not all of war's brutalities.

"As a picture editor, I've often had to make decisions about what the public needs to see and what is going to make the reader throw up," Morris says. "It's a fine line. At The New York Times, I had a bottom drawer full of pictures that were unpublishable, mostly because they were too much to take. One doesn't want to wipe the public in blood. One wants to get the public to learn to avoid bloodshed."

Even if the bloodiest images were published, Afghanistan photographer Louie Palu says war pictures still miss some important elements.

"I'm not really showing what it's like," he says. "You have to imagine people screaming and moaning, the last sound before they die, the smell, men weeping, the sound of flesh as people drag a casualty down a trench."

The more you've seen of death and inhumanity the more it turns you into someone who really can't stand the sight of war.

No photograph can capture the full horror. You have to be there — fight the war — to get it. And war photographers have to take enormous risks to get the pictures that will make an impact. Morris, a Quaker, says most of those picture-takers — the ones who witness in our behalf — are fundamentally opposed to the very evidence they are capturing with their cameras.

"Photographers, generally, who risk their lives are pacifists, but they sometimes question whether their work has accomplished what they hoped," he says.

Burnett agrees. "The more you've seen of death and inhumanity, the more it turns you into someone who really can't stand the sight of war," he says.

This exhibition at Washington's Corcoran Gallery has that effect on visitors. They walk away in silence, their heads down. The pictures — on view through the end of September — are, mercifully, the closest many of us will get to actual combat. Yet seeing them changes — and sobers — viewers. And reminds us there are still men and women out there, experiencing and documenting war, on our behalf.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))