San Diego County has contracted with the Affirmed Housing Group to build an affordable housing complex in Chollas View, on a Market Street lot that used to house the Health and Human Services Agency’s Southeast Family Resource Center, and now sits vacant.

It would contain 137 one-bedroom apartments for low- (less than $57,900 yearly) and extremely low- (less than $28,950 yearly) -income seniors, with an on-site child care center and a community garden.

The county’s Director of Housing and Community Development, David Estrella, said the project meets a dire need.

“For our seniors that are on fixed income, that are struggling to meet their daily needs and really don't have as many opportunities for maintaining their housing, a property such as this one will provide them the kind of stability that they need,” he said.

The county is in a housing crisis. A spokesperson said it’s short about 120,000 homes, based on a state assessment of overcrowding, cost burden, vacancy rates, and jobs-housing imbalances.

They plan to build at least 10,000 affordable units on government land by 2030.

State law requires the county to use no longer needed land for affordable housing, whenever possible.

There are 11 planned housing sites on surplus land so far, most in the San Diego metro area, including the lot in Chollas View.

Area neighbors said the proposed complex is a great plan — for somewhere else.

Here, they said it's worsening issues the Civil Rights movement tried to address.

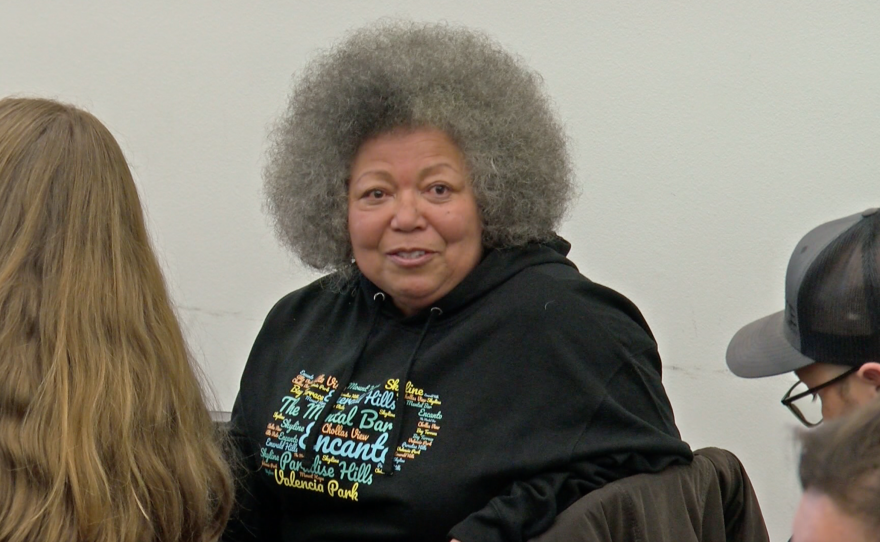

“The same problems that we had in 1963 is the same conversations we're having now,” said Marry Young, who sits on the Chollas Valley Community Planning Group. “Poor schools, segregation, the concentration of poverty.”

The state identifies Chollas View as a “low resource” area. It has higher poverty rates and lower education and employment levels and home values.

Locating this development there would increase the portion of neighbors living in poverty, residents argue.

Young said the county’s land use choices are making disparities worse.

“They make these decisions to continue layering poverty on top of poverty on top of poverty, and thinking that the outcome may be somehow different,” she said.

Research indicates this issue is racially skewed.

Poor white families tend to live in communities with lower poverty levels overall, writes Princeton sociologist Matthew Desmond in his 2023 book “Poverty, by America.”

Poor Black and Latino families more often live in communities with higher poverty overall, and face unique hardships that result from personal poverty colliding with community poverty: less resourced schools, less safety, more police violence and lower-quality housing.

About 80% of Chollas View residents are Black and Latino.

Young said small decisions — like where to locate one affordable housing complex — chips away at the residents’ long term growth.

“Whatever wealth that everybody is talking about that we should be building, it doesn't happen because it's chiseled away,” Young said.

In 2016, the community planning group published a plan to address this.

It dictates that mixed-use developments should use the ground level for things like retail, offices, grocery and drug stores. There should be affordable home ownership opportunities, not just rentals, for middle-income households, to help alleviate the community’s overall poverty level and bring more resources in.

Planning group members said they weren’t consulted by the county before the purpose and developer for the land were chosen, and asked why the development doesn’t follow their goals.

A county spokesperson said the developer has just begun community outreach to ensure the residents have input on the design and services of the complex.

Jacinta Hinojosa, who lives near the lot, said the affordable housing complex was news to most of her neighbors.

“A lot of people don’t know things are getting built around your community,” she said. “People don’t have the time to attend (meetings), are working, or they don’t have the right language.”

She wants to see the lot used for green space — something to help ease the effects of climate change, like the recent flooding, she said, which hit low-income neighborhoods of color the hardest.

Her 13-year-old son Alonso wants a park.

“I think it’s important for kids to play outside, not just be inside all day,” he said.

Planning group members argue the land didn’t have to be declared surplus. It could have been used for something like a park.

They said affordable housing could be located somewhere with more resources — higher wealth and more employment opportunities — to give the seniors a shot at better outcomes without worsening already existing poverty.

Housing director David Estrella said he understands their concerns, but has also heard from people who need housing.

“Folks that are formerly homeless, folks that are just starting off their families, folks that have jobs that are working and just can't find a place nearby where their work is,” he said. “And so we balance the needs of the region and the community within itself.”

Developers plan to break ground on the Market Street property as early as December of 2025.

Community members said they might also be there, with picket signs.