Just before 8 p.m. on Saturday, April 27, 1946, Alton Collier boarded the Coronado ferry to San Diego.

He never reached the other side.

His body washed up on the North Island shore of Coronado a week later.

Explanations of what happened to Collier differed, depending on which newspapers you read.

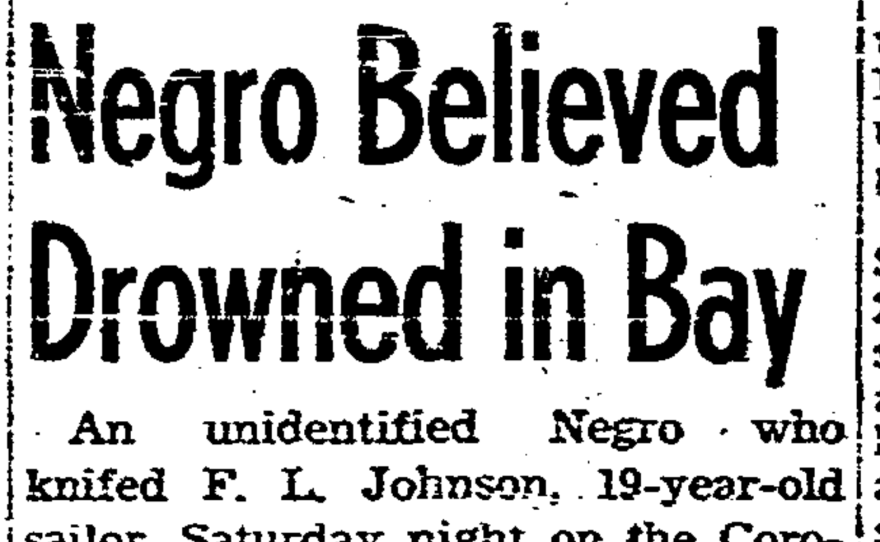

White-run papers didn’t use the word “man” in their headlines about Collier, but “Negro,” “suspect” and “knife assailant.”

In their accounts, Collier, 26, got in a heated argument with two 19-year-old Navy men, Freddie Johnson and Otis Gilbert.

Collier drew a knife, they said, and slashed Johnson on the arm.

So Gilbert confronted Collier with a pair of boat hooks.

Then, Collier leaped over the railing and dropped fifteen feet into the bay, a few hundred yards from shore.

Ferry crew dropped a life raft, but proceeded to San Diego – even though Alton Collier screamed for help after he hit the water.

This detail bothered Coronado historian Kevin Ashley, who stumbled on the story while researching the island’s African American history.

“Why would a guy jump into the water and drown if he knew how to swim? If he didn't know how to swim, why would you jump in the water?” Ashley asked. “Something didn’t add up about it.”

Ashley had taken up local history as a retirement hobby. His curiosity about this detail would lead him down a year-long rabbit hole of newspaper archives, court documents and public records. (In all his digging, he never found a photograph of Collier.)

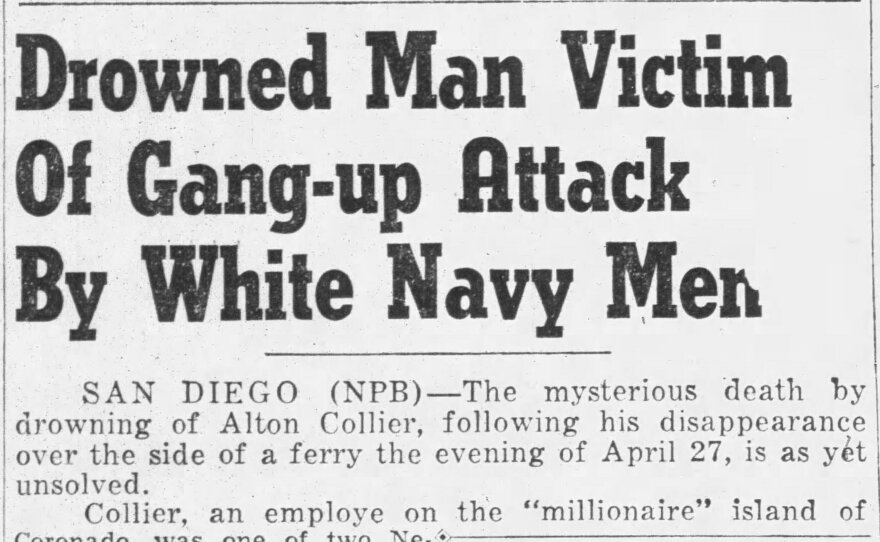

In Black-run newspapers, Ashley found a very different headline: “Drowned Man Victim of Gang-Up Attack By White Navy Men.”

In this account, witnesses observed sailors shouting at Collier: “There’s a n——r now!” and crowding him toward the railing.

Then the sailors struck him with a boat hook, causing Collier to fall overboard.

“The white press basically fed what I believe was a prevailing narrative of African-American men as aggressive, as assailants,” Ashley said. “And the Black press portrayed him as a victim of a murder based on his race. He was targeted for his race, and he died because of it.”

Race relations were boiling in San Diego in the months leading up to Collier’s death.

The American Council of Race Relations, formed to promote racial equality after World War II, conducted a study that found San Diego had the tightest restrictions on Black customers of almost any major city on the west coast.

And African Americans were picketing Logan Heights businesses that wouldn’t hire them, like a movie theater and a supermarket.

A thousand people jammed into a San Diego courtroom just weeks before Alton’s death, when the picketers were called to respond to a restraining order request by the theater owner.

So the story of Collier’s killing didn’t surprise Ashley.

He believes the ferry’s Navy passengers closed rank, agreed on a story and invented the knife.

What the press first portrayed as a knife wound would later be revised by newspapers to “more of a scratch,” Ashley said.

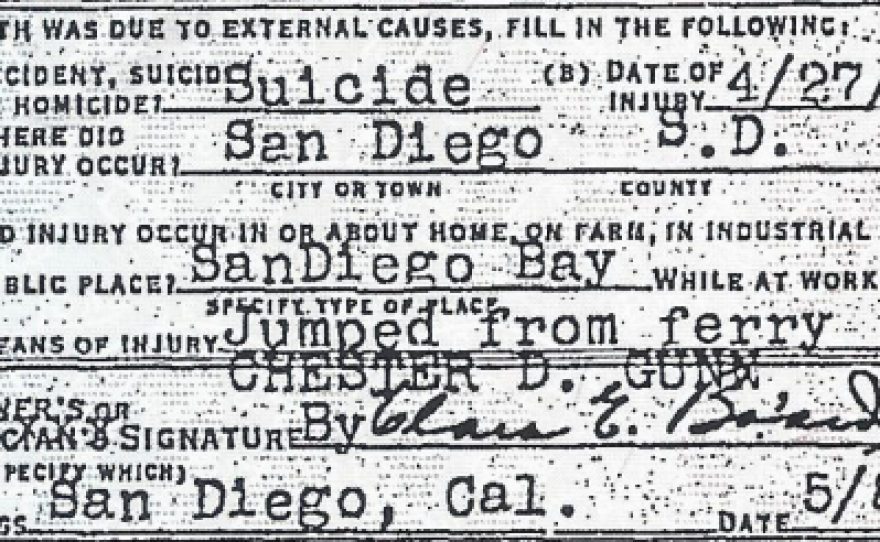

The coroner declared Collier’s death a suicide.

Collier’s wife, Georgia, sued the ferry company for $100,000.

At the time, it was owned by real estate and transportation tycoon John D. Spreckels.

Spreckels also owned the hotel that employed Alton Collier, and one of the newspapers that maligned him.

“Imagine this 23-year-old, 24-year-old African-American woman with a primary school education taking on the Spreckels Company,” Ashley said.

Her deposition paints a very different picture of Collier.

Like his eight siblings, Alton Collier grew up splitting his time between the cotton fields and a segregated school in Jim-Crow-era Texas.

When Alton was 8, his father died of Pellagra – a disease caused by malnutrition that silently killed thousands of poor, rural southerners and sharecroppers.

Alton turned the cards he was dealt into a surprisingly good hand by his ‘20s.

He became a cement worker and union member – rare for Black men at the time, Ashley said – making about $90 dollars per week at the Hotel Del Coronado.

He never drank, she said. He had asthma and wore glasses.

And, importantly, she said he never owned a knife or even a razor blade.

Georgia Collier told the lawyer: “He had no temper whatsoever. He never bothered anyone and he tended to his own business and let everyone else alone. That is the kind of man he was.”

She said that Saturday, he got off work before noon. He helped her wash the dishes and cook dinner. He mopped the kitchen floor and planted flowers in their garden.

Then, he boarded the ferry to pick up newly tailored trousers for himself and a topcoat for Georgia from a department store downtown.

They were supposed to go dancing that night.

But he never came back.

The Navy and Coast Guard searched the waters that night but didn’t find him.

She later identified him by his glasses found on the ferry deck, broken.

She knew then that he was gone. Her husband couldn’t swim.

Over and over in the deposition, Georgia said he was killed.

Her white lawyer, Rollin McNitt, was a powerful guy, Chairman of the Democratic Central Committee in Los Angeles County.

Spreckels was trying to sell the ferry company – a task made more difficult by a pending lawsuit.

The court dismissed the case.

Georgia Collier never received a dime.

A week later, the ferry company sold for $5.5 million.

The sailors were never charged.

After reviewing Kevin Ashley’s work, the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) declared Collier’s death a racial terror lynching.

He’s the third such victim EJI has documented as killed in the state of California between 1865 and 1950. The other two were lynched in Kern County.

There are likely more, said EJI senior attorney Sia Sanneh.

“We have always contended that there are likely thousands more racial terror lynchings than we can document, many of which may never be detailed because no media or contemporary account exists to confirm the allegations,” she said.

San Diego State University anthropology professor Seth Mallios said San Diego could lead a national reckoning with the broader definition of lynchings.

“You immediately think of these images from the deep South, and you think of hangings,” Mallios said. “But that's not what this is. Lynching is about people taking the law into their own hands, there being no representation, and terrorizing an individual.”

San Diego genealogist Yvette Porter Moore wants local accountability – for the County of San Diego to change his death certificate, which still lists suicide as the cause of death.

Ashley’s year down the rabbit hole inevitably brought his family with him.

Ashley’s wife, Caroline, hopes EJI’s recognition of Alton Collier’s death will give others courage to come forward with their own families’ stories that could qualify as lynchings.

Ashley’s daughter, Eliana, is thinking of Alton Collier’s surviving family.

“The true stories of racial violence were often just pushed under the rug,” she said. “The people who have to take the burden of that often end up being the families. They have to carry that trauma.”

Georgia Collier died in 1988. Alton Collier didn’t have children of his own, but his siblings did. Ashley is trying to reach Collier’s nephew, who he believes to live in Corpus Christi, Texas.

The Navy men are also dead. At 31, Otis Gilbert was found at home with a gunshot wound to his chest, gun in hand and a restraining order from his divorce proceedings nearby. Freddie Johnson died in 1998 at the age of 71.

They never faced criminal charges.

This is true of most lynching perpetrators. According to EJI, only 1% of lynchings after 1900 resulted in a criminal conviction.

Their research also finds that many lynching victims were never accused of any crime, only “minor social transgressions.”

On the 77th anniversary of Collier’s death last year, around 8 p.m., Moore and Ashley boarded the Coronado ferry to acknowledge his life.

“I just wanted somehow to say, like, ‘I know what happened to you. Maybe nobody else knows, but I know,’” Ashley said.

Collier didn’t get to see the flowers he planted that Saturday bloom.

On the waves he was left to drown in, Moore and Ashley threw fresh petals.

Ashley, Porter Moore, Mallios and others formed a Community Remembrance Coalition.

They are planning to honor Alton Collier with a public ceremony in mid-July.

They intend to collect Coronado sand to mail to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice museum in Montgomery, Alabama.

There, his name will be engraved in steel as a permanent testimony to the truth, alongside more than 4,000 other names, and acknowledgement of the thousands more still unknown.

A small sliver of justice, Ashley said. “Say his name, Alton Collier.”