When I met William Pink he was wearing a grey hoodie and a crushed hat that was lined with small pins. He held a stick with a string attached to the far end, and the string held a row of wooden rings.

“This is an acorn ring game,” he said. “These are the acorn caps from the interior white oak. And the idea of the game is to catch the rings.”

He tossed the row upward and a ring came down, impaled on his stick.

“Got one,” he said.

William Pink is descended from the Agua Caliente Cupeño tribe from Warner Springs. He has been devoted to remembering the stories, tools and technology that allowed his band to create a life in Southern California.

“In my 20s I went around and visited a lot of the elders, trying to learn things as much as I could from them. We were losing a lot of information so I spent a lot of time working with a lot of different elders, up and down the state of California,” Pink said.

We met on the campus of Cal State San Marcos at their ethnobotanical garden. Pink and I were joined by Bonnie Bade, a professor of anthropology.

“Southern California plants are so powerful because they provide medicine, food, construction materials, tools,” Bade said.

“What is technology?” Pink mused. “It’s how certain things were made and you have to employ certain tools to accomplish certain things. There were no metal objects. A lot of these were done with no metal tools at all.”

Mining fiber from stalks of the dogbane

Pink scrapes the side of a narrow wooden stalk with a pocket knife.

“So these are stalks from the dogbane plant. It was one of the major sources of fiber for textiles in the Native American community. There are two ways of preparing the dogbane. One is kinda blistering the bark off. You don’t want to scrape it. Because if you scrape it you destroy the fiber,” he said.

Pink said the fiber was also used to make fishing nets and anchor lines. They are water resistant so they don’t rot. He crushes the hollow stalks with his fingers and removes the fibers. He then twists them into braids to make them stronger.

“What are you doing now?” I asked.

“I’m spinning the cordage. And I’m going to let you try and break it,” Pink said. “I always offer to pay $20 to anyone who can break it.”

I wrap the fibrous cord around my opposing fists and pull with all my strength. It doesn’t break.

“I go home $20 dollars richer today,” Pink said.

The shadow of Indian Rock

The following week I met Mel Vernon and two other members of the San Luis Rey Band of Mission Indians. Vernon is the captain of the band that’s native to Oceanside and Carlsbad in San Diego County.

We stand on a protected plot of land, surrounded by tract homes and mountain peaks, where we find a tall sacred stone called Indian Rock.

“We’re in a place here in Vista. Undisclosed. Our tribe is the stewards of this big rock behind us,” Vernon said. “There were village sites around here and (the rock) has the red ochre drawings on it from young women who had performed their puberty rites. To become part of the tribe they would make their mark on this rock.”

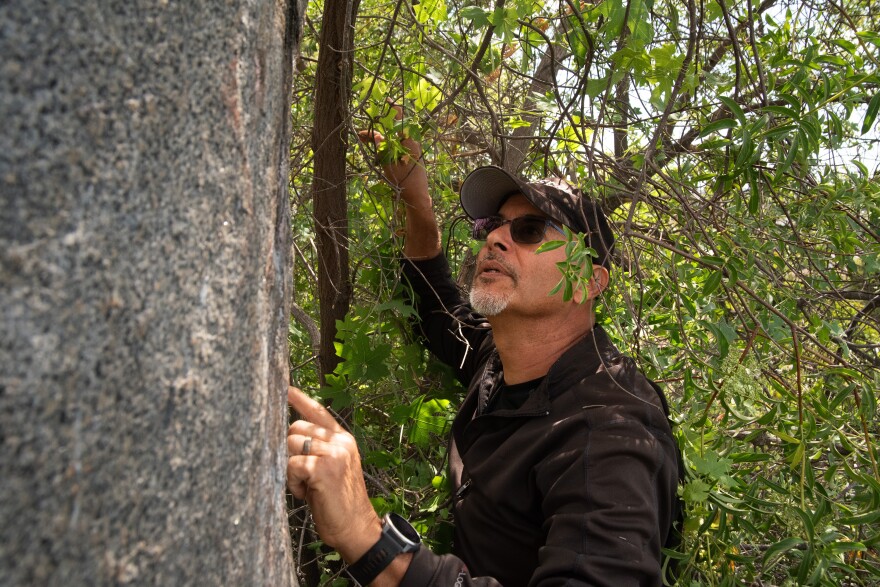

Indian Rock is surrounded by a garden of native plants. Michael Cerda is another member of what is often called the Luiseño Tribe.

“I’ve been kinda known in the tribe as a plant person,” Cerda said.

“We have about 65 plants here on this lot and about a third of them are medicinal. And science today is saying that our ancestors were using them in the correct way. And sure enough, there’s chemicals in there that do the healing. Anti-inflammatories. Antibacterial,” he said.

Like Artemisia Californica, called California Sagebrush, which Cerda said is an anti-inflammatory and a disinfectant. He stands in front of another plant with yellow flowers.

“People know it from the common name of elderberry. It’s medicinal. To our people it’s sacred because it’s saved some lives. It relieves digestive issues. Respiratory issues.”

Mel Vernon adds that medicine does have a somewhat different meaning among Native Americans. Healing isn’t always something that comes from a drug. It also comes from your mind and spirit.

“Even today, you have something that’s wrong and you think it’s wrong. And somebody says 'No, it’s just this.' And you feel better about yourself. And that's healing. Pretty much an instant healing,” Vernon said.

Indian rock has not been sheltered from the modern world. It has become a hangout for local kids and the graffiti on Indian Rock isn’t tribal. It’s vandalism.

Michael Cerda said they’ve taken steps to try to stop the disrespectful activity. They’ve planted poison oak around the rock and cactus around the property’s perimeter fence in an effort to keep people away.