San Diego County Receives First COVID-19 Vaccines For Military, Civilians

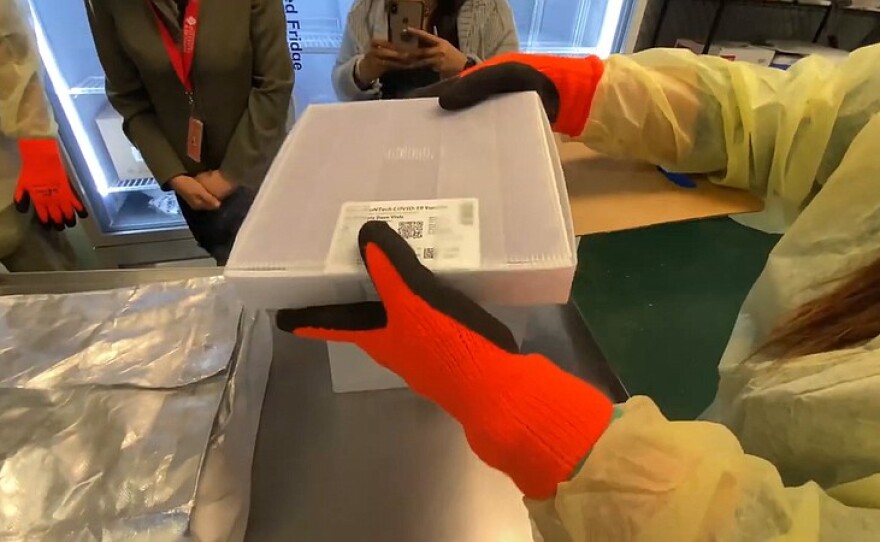

Speaker 1: 00:00 The Pfizer COVID vaccine begins its rollout in San Diego. Speaker 2: 00:04 I think there's totally expected that there will be another shipment of Pfizer coming in the next several weeks. Speaker 1: 00:11 I'm Maureen Kavanaugh with Jade Heinemann. This is KPBS mid-day edition. How are hospitals directing their resources as intensive care capacity dwindles? We manage Speaker 2: 00:31 Literally sometimes an hourly basis. Uh, the human resource needs that we have, which are really the most stretched to have all Speaker 1: 00:40 Does COVID care cost the same for everybody we'll begin tracking the bills and what neuroscientists are learning about Covance effect on the brain. That's ahead on midday edition. Speaker 1: 01:01 The Pfizer COVID vaccine is in San Diego. The first shipments have arrived in the first people. Vaccinated will be healthcare workers. That's the news from County officials after the vaccine received formal emergency authorization late on Friday, the first vaccinations have already taken place today, mainly in medical centers on the East coast. But the good news about the vaccine is slightly dampened by its very limited supply. San Diego's expected 28,000 doses are only enough for about 70% of hospital workers in the County. And only for the first dose. Joining me is San Diego, Dr. Rodney hood, president, and founder of the multicultural health foundation and a member of California's COVID-19 scientific safety review work group, Dr. Hood, welcome to the program. Speaker 2: 01:51 Thank you for inviting me. Where Speaker 1: 01:53 Are the shipments of the COVID vaccine being stored in San Diego? Speaker 2: 01:57 Well, uh, from my understanding, there are three places, uh, at, uh, children's Rady hospital university hospital, and at the County Speaker 1: 02:06 And each of those facilities have the very cold minus 97 degrees Fahrenheit apparatus that can keep this vaccine the way stabilize the way it needs to. Speaker 2: 02:19 Yeah, so, uh, they, uh, uh, that's why they're there. They're all have the capacity to a store. I think it's minus 70 degrees or more. And, uh, those are the three places that have the capacity and then the distribution we'll go from there. Speaker 1: 02:35 Do you know when vaccinations will begin here in San Diego? Speaker 2: 02:40 You know, um, I honestly do not. I think, uh, that is now being determined. I think, uh, each, uh, hospital where the vaccines would be a distributed, uh, kind of, uh, developing their own plan, but when the first vaccine will be given, um, uh, I can't tell you, but believe since it just came today within the next day or so Speaker 1: 03:04 Now the state review panel approved the vaccine after the FDA approval this weekend. What were those state discussions like? Speaker 2: 03:11 Well, um, they were, uh, quite, uh, uh, interesting. They were, uh, very intense, very thorough. What we did was review the, uh, FDA data that Pfizer, uh, presented to the FDA. Uh, it was, uh, quite, uh, expensive, not only talking about safety and efficacy, but, uh, folks should know the, uh, Pfizer study was over 44,000 individuals. Most of them were in the United States, but there were other countries involved, including Turkey, Germany, South Africa, and Brazil and Argentina. It had a diverse, ethnic, uh, background, but I think the most impressive thing was that the effectiveness of 94, 95% was seen, uh, consistent across all of the subgroups, all of the ethnic racial subgroups as well as, uh, age and gender. Speaker 1: 04:11 And why is the state recommending that the full 28,000 doses that are going to be given here in San Diego, be given as a first dose instead of saving some of the vaccine for the needed booster shot? Speaker 2: 04:24 Well, I think there's totally expected that there will be another, uh, shipment, uh, promised of Pfizer coming in the next several weeks. And so the, um, uh, uh, plan is is that when that, uh, second group comes that they will then get their second dose. Speaker 1: 04:44 Now hospitals in San Diego say they will not require their medical staff to get the vaccine. Do you agree with that decision? Speaker 2: 04:52 Well, um, I it's, it's kind of hard to force folks to get vaccines answer is a yes at this point, I don't think you should force anybody. I think there's a lot of education that needs to take place. I think that education has already taken place. I can tell you the surveys that I've seen over the past several months, including hospital staff are, are showing more acceptance. So a several months ago, um, the, the surveys and now showing in the recent usher is more and more are beginning to be acceptance of, of the vaccine. Uh, if there is a silver lining into the, a shortage, um, those that are not willing to take it at this time, many of them are not saying they won't take it. They're just not willing to take it at this time. So as more and more vaccine rolls out in is available, hopefully there'll be enough vaccine for those that have delayed taking it. So in essence, because we only have 28,000 that the ones who want to get it, uh, we'll get it. And then those that change their mind later, as the vaccine rolls out, we'll be able to get it. Then I believe as we move forward more and more people will be acceptance of the vaccine once when they hear how safe it is, uh, and, uh, get more information. Speaker 1: 06:18 There are some concerns that the strong reactions to the vaccine reported by some participants in the clinical trials will put off people from going in for the second dose. Do you think that may be a problem? Speaker 2: 06:30 Well, I think it's potential problem. However, I think that's why it's important to kind of educate folks that, um, yes, for this vaccine, we call it, uh, reactive genicity meaning when you get the shot, uh, there are, uh, local reactions to the shot that, um, we have seen a little bit more other vaccines. So in essence with the flu, uh, there's usually very little reactive genicity however, with this one, uh, what you see is local reaction, redness, little pain, and, uh, many times the reaction that people feel a little bit more after the second dose. So I think educating folks about that, uh, it should be, it's really a positive thing. It's really, uh, letting us know that your body immune system is responding. So it is not an unexpected, uh, event. It's not an unexpected side side effect, but I think if you educate folks about it, uh, there'll be less hesitancy. We have seen this with other of vaccines. So, uh, for instance, with the, um, uh, shingles vaccine, that's a two dose vaccine, uh, there's a little bit more reactivity, uh, to that vaccine than the flu vaccine. So, uh, this should not be, uh, deter folks from getting it. And I think with education, um, that, uh, uh, that hopefully won't be a great problem from preventing them from getting it. Speaker 1: 08:05 I've been speaking with San Diego, Dr. Rodney hood and Dr. Hood. Thank you so much for speaking with us. Speaker 2: 08:12 Welcome. Thank you. Speaker 1: 08:19 COVID-19 cases are continuing to climb in San Diego County and with that comes an increase in hospitalizations for the disease, but state metrics show, I see you availability is shrinking KPBS, health reporter Taren mento ask the leader of sharp healthcare, how they're balancing resources, amid demand. She spoke with sharps chief operating officer, Brett McLean, Speaker 2: 08:44 If there will be enough resources to go around. So just tell me what it's like managing resources in your facilities right now, without the incredible analytic support that we have in PR in particular at sharp. Uh, we Speaker 3: 08:56 Would not have been able to, uh, whether this, uh, as good as we have we manage on literally sometimes an hourly basis. The human resource needs that we have, which are really the most stretched of all. Uh, we managed the bed capacity and the type of beds, uh, whether those are typical med surge, uh, hospital beds or ICU, uh, et cetera, we manage the, uh, incoming volume that will normally come through our emergency rooms and our trauma rooms every single day. And we manage the supplies. Uh, so it is, uh, uh, really a throughput work, really, uh, engineering feat. Uh, and we just have a super talented folks, uh, managing this on a daily basis. Speaker 4: 09:41 Several reporters were asking the County, um, during their news briefing, you know, how will decisions be made when we have more need than we have staff space equipment. So who is the authority on making those decisions? Is it you, does it come down to you Speaker 3: 09:57 Right now? Uh, the direction that's coming down from the state is that we're not under that order to stop all non COVID cases, right? So every health system comes together on their own and makes decisions on the specifics. Uh, we at sharp are lucky enough to have, you know, multiple sites and multiple different places that we can provide different low levels of care. So we're making decisions on a daily basis to move patients from one hospital to another, if there's room and space in order to manage our COVID population, uh, as well as our non COVID population. So that is something that we, uh, that we do on a daily basis. And I'm absolutely involved in that. We, we actually have a small team that meets twice a day, clinical leadership at each of our facilities, uh, every morning at seven 30 and every afternoon at five, to talk about what's going on right now, what can we do within the system? What do we need to do to find more resources, uh, that one placement have versus another. Uh, and then we make decisions, uh, moving forward for the next day or the next week Speaker 4: 11:02 You are though just, uh, many facilities, but just one healthcare system in San Diego. Um, and so responding to the need does go beyond sharp. How are decisions on resource allocation at other facilities, their system, just like you described affecting Charlotte? Speaker 3: 11:20 Uh, well sharp is the lady, uh, provider, uh, in San Diego. There are other, uh, very substantial, uh, systems as well. We actually communicate every single day, seven days a week together on what our volumes are, what our, uh, what we've found in terms of testing, what those rates are. We take a look at Voya. Is there something happening with both us since scripts, maybe in the South Bay at Chula Vista? We look at that, we communicate that bank back and forth. That partnership has really helped us, uh, to identify where peaks and valleys may be coming, but it also allows us where, where possible to move patients within facilities as well. It's a, uh, not a common, every single day thing, but it does happen. Uh, and we work together based on, you know, what those, uh, what those volumes are telling us that we need to do. So that process has been fantastic. Speaker 4: 12:14 Have you had any trouble with other facilities taking patients when requested for a transplant? Speaker 3: 12:20 I, I would say, uh, to date, uh, the issues around any type of difficulty in transferring has really not been a space issue to the significant issue is staffing. Uh, and we're all dealing with the same issues of, uh, the same, uh, poles of staff, uh, that are exhausted, that, uh, are working, uh, like I have just never seen anybody work before. It's just amazing to spend time, uh, at the front lines and just watch and observe what's happening. Uh, we've got, you know, dwindling pools of traveler nurses because the whole country's going through the same issue, right? So there's certainly a lot of, uh, competitiveness if you will, and at different rates and all of that. So, uh, that is, uh, pulling, uh, some staff, uh, into other areas, but it really is around, uh, staffing. That's, that's the issue. So if we have the difficulty maybe accepting a patient that needs a transfer, it's not, uh, to date, it's not because of space, it's because of not having the appropriate right. Kind of staffing. And maybe we need another five, six hours to fix that, to be able to, to move on. And I would say that's the case for everybody. Speaker 4: 13:31 Is there risk to the patient? Would that delay? Speaker 3: 13:36 The patient is still typically in a, another care facility. Uh, and we have, you know, let's say, uh, you know, uh, in our emergency room, we may have an ICU patient that's in there. Uh, that's been deemed to be when we find a bed will be an ICU patient, but we still have, you know, significant resources in the, in the emergency room from staffing and the doctors, uh, and, uh, all of that to care for that patient. And, uh, in a very similar way that they would be cared for on the, on the ICU, but it's going to delay things. It's gonna delay, you know, other patients that are coming in they'll have to wait longer. It will, you know, the system will just get slower and slower, you know, because of that. But it, it is the thing that keeps me up right now is, uh, capacity and, uh, the ability to have enough staff to care for these patients, which is why, uh, we're just in this window right now, have the ability to bend this curve down. Uh, again, I, I really feel that we have, uh, you know, at least probably three tough months ahead of us, but we can make those three months better by right now today, changing our behavior is changing the way in which we, uh, spend time with each other. And, uh, you know, uh, where are our mask, Speaker 5: 14:55 But we have heard, um, from projections presented at a County board meeting that by Christmas, we will be full. Is that the impression you're operating under as well? Speaker 3: 15:05 Yeah, I am, uh, upper in under both, uh, that as a major fear, uh, that it's going to get worse and I'm also operating under, uh, the hope that, uh, we bend that curve together and do the things that we need to do to, uh, make these next couple of months, uh, uh, as good as they can be. So I'm hopeful, uh, but we have to prepare for the worst. And so that's, uh, that's the work that we do every day. What is the worst? I think the worst is that, you know, hospitals are full. Uh, and when you say that again, I mean that from both a space, as well as a resource or a staffing perspective, that we are, uh, having to enact some of our, uh, federal, uh, help, if you will, for some of the, you know, uh, other sites, uh, the mobile sites, tents, uh, things like that, uh, that we will have more and more delayed care, meaning people won't go to the hospital when they have that first a twinge of chest pain, right? Uh, that's super dangerous. That is not a, that is not what we need to be doing, but that's on my list of things, uh, of the worst is that those, you know, that stuff still happens. People still have heart attacks, they still get in car accidents, they still have strokes. Uh, and we need to care for those patients as we do now. So that that's the picture. I hope we don't see that was KPBS health reporter Taryn. Speaker 5: 16:28 Mintos speaking with sharp COO Speaker 1: 16:30 Brett McLean. [inaudible] this is KPBS midday edition. I'm worrying Kevin with Jade Heinemann San Diego researchers think plants may offer a significant way to draw down excess carbon in the air that carbon is feeding a cycle. That's warming the planet's climate KPBS environment. Reporter Eric Anderson says there's a lot riding on the local research, greenhouse manager, Speaker 5: 17:16 McKenna Hopwood opens the door to what she jokingly calls the meat locker. Okay, there we go. Bags of drying plants, both stocks and roots hanging from the ceiling like slabs of meat in a cooler, but of course they're plants. So, um, these have all been root washed and then processed. And then they've been drying for about a week, um, depending on the crop, we'll drive them for about a week to two weeks, and then we'll throw them in the planter and oven for a day or two. And then we'll do our biomass weights. This is the final stop for plants raised Speaker 6: 17:50 In the salt. Greenhouse Hopwood is constantly growing several different plant species here. Speaker 7: 17:58 Um, some plants don't really like to be watered from the top and these ones are really sensitive. So if they have soil that gets tossed into the middle of the plant, they won't produce their flowers. Speaker 6: 18:08 Some of these plants grow fast seed to harvest. In a few months, others are crop plants like corn soybeans and wheat add in sorghum, rice, and canola. And that's most of the popular food crops grown in the world. Total plant acreage is about the size of India. Speaker 7: 18:26 One of the biggest challenges we think, and the biggest threat, um, for, um, humanity is the climate crisis. Speaker 6: 18:34 Wolfgang Busch is looking for ways to make these widely used plants a lot better at moving carbon from the air and storing it deeper in the ground. He's using millions of dollars in grants to develop longer and deeper root systems. And they are the key to storing carbon that the burning of fossil fuels spews into the air. Speaker 7: 18:54 And we're trying to find, um, um, mechanisms, genetic recipes, if you want. So to actually make better plans or make plans better in storing larger amounts of carbon underground for longer in the soil, Speaker 6: 19:07 Bush hopes to find the right combination of gene manipulation and breeding and the transfer of desirable traits from other plants to make those six crops better at carbon sequestration, Bush says they represent a short-term answer to a long-term problem. Speaker 7: 19:24 And there are currently only actually no really scalable methods to draw down carbon dioxide except from plants. So if you think about this in the long run, this technology will enable, uh, carbon draw-down. Um, that is really urgently needed to get back to, uh, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere that are safe for us, Speaker 6: 19:45 But the clock is ticking. The planets average temperature continues to climb at dramatic rates. Bush says it'll still be about five years before he's likely to develop the plants that he's confident will help. It could be 15 years before enough of those plants are planted to make a difference. Speaker 8: 20:02 I think we can. We're really right on the edge Speaker 6: 20:06 Soccer searcher, Joanne Corey says temperatures are rising because people push more carbon dioxide into the air than what the planet can handle. She understands the urgency, but remains hopeful. Speaker 8: 20:19 So everything, you only have to get those 18 times that the earth can't deal with. That's a small part of what plants push your mind on a regular seasonal basis, right? They're pushing around more like 800 agents. Speaker 6: 20:35 Thanks. Plants can pull about four gigatons of that extra carbon out of the air and put it into the soil, building out more renewable energy and making cars electric could help too. But those transitions will take time. Cory thinks developing plants that can move the carbon out of the plant sugars and into non-biodegradable polymers. Buried deep and roots could buy some time until other solutions come along. Take some Speaker 1: 21:01 Wheat right here. It's been growing a little long Speaker 6: 21:05 Kind of Hopwood is spending that time in search of a scalable solution in the salt greenhouse. Just take this guy, transplanted it, but success here and in the lab will have to be duplicated on a global scale. Researchers are confident. The science will help them improve the plants, but they don't share that optimism about governments and farmers will have to implement the solution before the climate gets too warm. Eric Anderson KPBS news, Speaker 1: 21:34 Joining me is rom Ramanathan distinguished professor of atmospheric and climate sciences at the Scripps institution of oceanography and renowned climate researcher. He's led efforts to mitigate climate change with the United nations, the national Academy of sciences, the state of California, and with the Vatican and welcome to the program. Speaker 9: 21:54 Thank you for inviting me. Speaker 1: 21:56 The researchers who are developing these plants to remove more carbon from the atmosphere, think it would take at least 15 years for plants like this to have a significant impact. Won't we have seen major damage from climate change by then Speaker 9: 22:12 Quite a bit. Uh, in fact, uh, teaming a bit sub colleagues. I published a study two years ago saying that we are going to cross the next dangerous threshold of warming in about 10 years from now, but by 2030. And, uh, I am personally, uh, if I'm spending sleepless nights, it's on this point, uh, to me, it looks like we are going to take another three to five years to recover from this COVID crises. And by then the new crises would start in terms of climate change. The warming of, uh, another dangerous threshold, which is degree in half as of 2015, the planet has already worn by a degree. And by the time it goes to one and a half, that's the planet we have not see in the last hundred and 25,000 years. So be you're going to be crossing such unprecedented threshholds every 10 to 15 years from now onwards, unless we bend that warming curve and to bend the warming curve, you have to bend the emissions curve. Since we have deleted so much bending the emissions curve by itself is not enough, uh, via put so much pollution close to a trillion. Tons of pollution is up in the air. We got to suck that out of the air, this making the plants, uh, roots, uh, go faster and longer to take the carbon is one of many, many, many ways we need. Speaker 1: 24:08 So is there a point of no return where we can no longer influence the trajectory of climate change? Speaker 9: 24:16 Uh, the Marines, uh, unfortunately, and thirdly, yes. Uh, as I see it, it is not a single point of no return. Uh, it's going to depend on who, you know, what 10 years from now, if you have not been that warming curve, I expect, uh, at least a 3 billion people. They are what I call on bottom 3 billion, not for any pejorative reasons. They are on the bottom of the energy ladder. They have no access to any, uh, clean energy, even for basic things. And with the degree on the heart warming that may have a huge deception for them in their ability to make a living in that ability to maintain just a basic living standards. That's 10 years from now. And then let's go to the middle, a 3 billion, and they're the ones living in cities, maintaining or basic services for them. I think, uh, where they are going to be severely, severely impacted irreversibly. Speaker 9: 25:33 It'll be another 20 to 25 years from now. When the warming reaches about two degrees, that would be catastrophic for them. And then is the wealthiest 1 billion. I am part of this, and many of us are. And for us, the point of no return will come beyond 2050. When the warming could go beyond two, three degrees. By the time you've got a three degrees warming, that's a planet we have not seen in the last 25, 30 million years. We don't even know what's waiting for us the next 10 years, Rican traverse all this dystopian nightmarish scenarios. It's in our power. We can still do it. Speaker 1: 26:21 We are currently moving away from an administration in Washington that basically denied human caused climate change to one way of preventing further climate damage is a very high priority. What are you expecting to see from the new Biden administration? Speaker 9: 26:38 I think the first thing we need to do is, uh, joined the global community, particularly the Paris agreement. And you ask, why, why do we need all of this? Why can't we just cut our emissions? Uh, my answer is that, uh, these pollutants state, once you dump them into there, they stay for decades to centuries. So pollution anywhere is global warming everywhere. Okay. So we got to cut these emissions more wide. And for that, I personally feel it requires American leadership, American technology, and, uh, the American ingenuity to solve problems. So we need to cut our own emissions down. And in that regard, I like very much the plier, the president elect has already announced and what I would like to see an aggressive global leadership so that we shared over technologies. We share our knowledge. So every country like India, Africa, China, they can bring the emissions down. Speaker 5: 27:51 I have been speaking with Rama, Rama, nothin, distinguished professor Speaker 4: 27:55 Of atmospheric and climate sciences at scripts. And I want to thank you so much for speaking with us. Speaker 9: 28:01 Thank you, Marie, Speaker 5: 28:06 For the last nine months, officials have assured us testing and treatment for COVID-19 is affordable, but is that true? Well, a project between, I knew sources, Joe Castellano and KPBS health reporter Teran, Minto hopes to answer that question and both of them join us now. Taran. Jill. Welcome. Thank you. Thanks. Hey, Taron, I'll start with you. What prompted this project? Speaker 4: 28:30 Yeah. Th the New York times has done some excellent work on surprise medical bills and found that some patients were receiving unexpected charges, not covered by insurance. Even a resident in a nursing facility told the times that they had a COVID fee to cover personal protective equipment. Another COVID patient saw a similar PPE charge on a bill for an ambulance ride. The time referred to this as the COVID charge, they also reported on surprise fees for, for out of network services, uh, that the patient wasn't aware they were receiving. So we're looking to see if any of this has happening in San Diego County Speaker 5: 29:05 And Joe, you know, aside from looking at San Diego County, what do you hope to find out from him? Speaker 4: 29:11 Well, we know medical bills can be really expensive. There are cases where patients are being charged a lot of money for COVID testing or treatment, and sometimes they had no idea it was going to cost that much. We also know some providers are charging more than others for the same services, which shows a problem with equity in our healthcare system. So we're trying to understand why these situations are happening and prevent residents from facing the same problems in the future. Speaker 5: 29:38 Karen what's the reason some medical are so expensive despite government assurances that they won't be Speaker 4: 29:45 Right. There are, there are laws. Um, insurance companies are required to pay the full cost of COVID-19 testing without charging a patient, anything. And if a patient receives care at an out of network facility, they're not supposed to face higher charges for that, but if they go to a facility in their network and a doctor there happens to be out of their network, then that could cost more. So there are exceptions to treatment and testing, and that's what we're looking into. We're trying to learn from our audience when these happen and then dig into why it's happening. Speaker 5: 30:17 And Jill, you all mentioned in your call out that some high medical bills related to COVID-19 are just unavoidable. Can you tell me about some of those situations? Speaker 4: 30:26 Absolutely. One of the most common scenarios is ambulances either on the ground transport, or when it gets really expensive is helicopter rides. If you're unconscious, it might be the case that you need to be airlifted to the hospital and you have no control over that situation. You certainly don't have to have control over who operates that helicopter, who owns that helicopter, what agreement that owner has with your insurance company or with the hospital you're being flown to. So, because of all those factors, there are cases we've seen where people are being charged tens of thousands of dollars for these helicopter rides. There was one recent study that found as many as 71% of ambulance rides could result in surprise out of network bills. Speaker 5: 31:10 So medical transport is one thing Taryn talked to me about some of the hidden fees in these medical bills that you're, that you're hearing about, Speaker 4: 31:17 Right? So the times has reported, you know, that some nursing homes and dentists are charging customers, extra fees without letting them know beforehand, to maybe make up the money that they're spending to acquire that personal protective equipment for their workers. And the times called these COVID fees. And that could be around 25 or 50. Speaker 5: 31:33 And so then Jill, tell me about these medical offices and facilities. Can they realistically offer COVID testing and treatment at an affordable price and, and are they given resources to do so from the government? Speaker 4: 31:46 Yeah, that really gets to the heart of this project. We know here in San Diego County and state testing sites are fully covering the cost of testing and charging $0. I've gone to these sites and paid $0. We've started to have people write into our call-out and say they haven't paid any money for going to these County and state sites. But we also know there are other sites out there and that we need those other sites that are not County or state run to meet the need in San Diego County. And we've started receiving responses from people saying they've paid as much as $160 for testing at some of those private sites. So the question is, are those private providers receiving enough financial support from the government to make testing and treatment affordable? And if they are, why are they charging so much? Basically we want to know, could COVID healthcare be less expensive than it is right now? Speaker 5: 32:35 And Taryn, we keep mentioning this call out. What do you need for people to this to do well, they can help us by, by telling us, you know, what have you been charged for COVID-19 testing or treatment, and then spreading the word about this project, uh, and to answer the questions about what you've been charged, you can go to kpbs.org/covid cost. Uh, and because this is an I new source KPBS partnership, you can also email covid@inewsource.org, also KPBS, and a new source or on Twitter, Jill and I are on Twitter. So you can tweet us there. And we've, we've both pushed Ben mom pushing out the link. That'll take you back to how you can answer these questions. I've been speaking with and Minto KPBS, health reporter, and Jill. Castellano a reporter with I news source. Thank you. Both of you. Speaker 10: 33:22 Thank you. Thanks. Speaker 5: 33:27 The California restaurant association says up to one third of the state's eateries might not survive the pandemic. That number could be significantly higher in the Bay area and Los Angeles County, where immigrants who are particularly vulnerable to changes in the economy make up a larger share of restaurant donors. Kcrws Benjamin Gottlieb spoke with restaurant tours in the San Gabriel Valley, just East of LA it's home to a vibrant Chinese American food scene. Speaker 11: 33:59 It's lunchtime at NBC seafood restaurants in Monterey park. I'm sitting with Genevieve Ko on the last day of outdoor dining in Los Angeles. She's a recipe creator and also editor for the New York times cooking section. And she grew up in this part of East LA County on the menu. It Cantonese staple. She grew up eating dim sum. Speaker 10: 34:22 This is a steamed rice roll with a roasted pork with Josue. So dig in Speaker 11: 34:29 Enjoined, dim sum comes with the type of dining experience tailored for a large banquet hall. You know, the place red carpeting, no-frills white tablecloth round tables that sit 12, Oh yeah. Tea kettles that are always full, but with outdoor dining now on hold in LA and in other parts of California co says, there's a real risk places like this one just won't make it. Speaker 10: 34:52 A lot of these other restaurants actually closed even before COVID. And so this was one of the last few that are going to be named. Speaker 11: 34:59 Other restaurants that had been doing relatively well with outdoor dining are beginning to struggle. That includes popping yolk in nearby Alhambra. Speaker 10: 35:08 All right, so this is going to come up to nine 10, and you're running about 15 minutes. Speaker 11: 35:12 It's a brunch spot owned by Jason side, Speaker 12: 35:15 Pumping the Oak is designed for timings. It's not designed for, to go. So it wasn't really work because nobody coming over here together, Eric Bennett, they to go. I mean they did, but that a lot of people, you know, nobody coming over here and say, I want a grabber French toast to go, you know, or me most out to go. They want to Amy. Speaker 11: 35:35 So I says, he's staying open for, but with eight grand and rents and utilities, another 20 for his wait staff and a chef, he just doesn't know how long he can last. And it's a similar story down the road at John non-spring in Alhambra Francis Chang says, she's hoping news of a vaccine will bolster business at her restaurant. Boom, Yamila tonight. This isn't going to end until there's a vaccine on just because it's going to be open, close, open, close. And so the short term is, you know, everyone is getting used to having to order takeout either online on the phone, there is some financial help on the way governor Gavin Newsome says he's extending the tax deadline for restaurants by three months in LA is offering upwards of $30,000 for payroll than other business expenses for now, for these restaurant owners, it's all about adapting, gritting your teeth and hold little luck that was KCRW Speaker 13: 36:35 Benjamin godly reporting from the San Gabriel Valley. This is KPBS midday edition. I'm Maureen Cavenaugh with Jade Hyman scientists have only been studying COVID-19 for less than a year, which is why information about it continues to change and evolve. KPBS reporter Beth Armando has always been fascinated by the brain. She asked UC San Diego health. Neurointensivist Dr. Nevas Koran JIA about how COVID can affect the brain. So I'm someone who's always been fascinated by how the brain works. And I tend to gravitate to pop culture that explores themes involving loss of identity and mind control and yes, the zombie apocalypse. So this also means that I love picking the brains of neuroscientists. Like Nevas Karangi of UC San Diego health. Now you specialize in something called neuro critical care. So explain what that means. I'm an ICU doctor that cares for patients with severe brain and spinal cord injuries, like big strokes, brain hemorrhages, brain infections, uh, trauma tumors. Speaker 13: 37:46 So I've done four years of specialty training in neurology and another two sub-specializing in neurocritical care. And now at UCFD, I lead a dedicated team of neurosurgeon stroke doctors and nurses in our neuro ICU is to help our patients recover. So what are the ways that COVID can attack the brain and how does it affect the brain and nerves? The thing that's tragic and fascinating about COVID is it can affect the brain and nerves and so many different ways. For example, the damage it causes to blood vessels can lead to strokes and brain hemorrhages in up to 6% of hospitalized patients, low oxygen levels caused by the lung and heart injury can damage the brain and the inflammation itself from the infection can affect the brain and the nerves causing confusion and delirium in the majority of patients severe COVID. It can also directly infect the nervous system in a mild cases. Speaker 13: 38:42 It can cause loss of taste or smell or in severe cases. It can cause meningitis. We've also seen a cause and an auto-immune reaction where the body's antibodies to the virus accidentally attack the brain and nerves. And that can cause life-threatening issues like brain swelling and Jamberry syndrome. And finally, there are psychiatric symptoms that are being reported where seeing people with hallucinations, even psychosis, uh, even after mild COVID disease, um, which couldn't be from brain involvement. And then there's the anxiety, depression, and PTSD PTSD due to the psychological trauma of being hospitalized with a frightening disease. Speaker 14: 39:24 Is this disease seeming to do something that's new and that's never been seen before, or is it just affecting the body in ways that are causing these neurological problems? Speaker 13: 39:36 So it's not that these things have never been seen before. We've seen them to very small degrees in, uh, in other viral infections, but I think what's different about COVID is you've got no immunity in most people. And so the effects are, uh, are proving to be very severe and much more common, um, in the nervous system than we're used to seeing in other viruses, because most people have some immunity to those viruses. One of the unique things about COVID though, is that effect on the blood vessel lining that causes clots everywhere in the body. This is not something we've seen, uh, from common viruses before. And that's why the effects of COVID seem to be, uh, more devastating and causing more widespread organ damage than we're used to seeing with other viruses. Speaker 14: 40:32 So can you talk about some of the specific neurological problems that COVID can cause some specific examples of things you've seen or that have been documented Speaker 13: 40:41 The neurological problems related to COVID can range from mild like headache or loss of taste and smell, which are very common in symptomatic patients to more concerning things like difficulty concentrating or thinking which people are calling brain fog, uh, to confusion and delirium. And then there are the life-threatening complications that we've seen, uh, strokes from those blood clots. I talked about brain swelling, seizures, coma from infection and inflammation of the brain, uh, paralysis from auto-immune attacks on the nerves. Uh, what I'm seeing most commonly is delirium in the very sick COVID patients. And we've seen a number of strokes as well, both of which can have permanent consequences. And although they happen more frequently, the more severe the patient's COVID symptoms, it's important note that these neuro emergencies can even happen to patients with mild respiratory symptoms. We've seen some young patients with minimally symptomatic COVID with no stroke risk factors come in with devastating large stroke. Speaker 14: 41:47 So are the neurological complications coming mostly from, or by COVID causing strokes and, and, uh, you know, depriving the brain of oxygen or does the virus actually just directly attack brain cells? Speaker 13: 42:04 So the problem with this virus is it can do both. So there are plenty of reports of meningitis and encephalitis or inflammation of the brain from the virus infecting the brain. Um, we also know that even in minimally symptomatic patients, uh, when they, uh, have an MRI, they can demonstrate evidence of inflammation of the brain, even if they don't have neurologic symptoms. So the exact number of patients that's, uh, that are having, um, neuro invasion is unclear, but because an early symptom of COVID is commonly the loss of smell and taste, which, uh, is carried by the nerve from the nose that goes directly to the brain. The olfactory nerve, we are concerned that direct invasion of the neurosystem is happening in a much larger percentage of patients than we would normally expect with, with, uh, with a virus like this. The stroke complications are happening in about 6%. Um, depending on the study that you read of is hospitalized COVID patients and they happen more frequently. The more severe the COVID is. So, uh, those, um, complications, although less frequent are, uh, are, are pretty devastating. Speaker 14: 43:32 So what might be the dangers of these neurological complications from COVID as we kind of move forward, Speaker 13: 43:38 But for the more severe neuro complications of COVID like stroke or Kian, Buray the risk of death or permanent disability is very real. For example, with stroke, mortality is around 20% and permanent disability, um, happens to about 50% of stroke survivors. And even if you don't have visible damage to the brain from COVID just being in the ICU and being delirious puts you at high risk for what's called post intensive care syndrome or pics, which can lead to persistent fatigue, cognitive problems, similar to Alzheimer's and psychiatric problems like PTSD for years, following discharge from the ICU. So moving forward, if we can all try to be patient and continue to wear our masks and social distance, so we can slow the pace of infections, it will give time to do the research, find out what really works and help make sure there's an ICU bed for you or your family. If you need it. This, I think is a, is a team sport. One of my colleagues said, teams, human against team virus. And the game is changing as we go on, but it's like that saying United, we stand divided. We fall. If we all work together, we can beat this thing. Speaker 1: 44:55 That was Dr. Nevas Karangi, uh, speaking with Beth OCA, Mondo, she shared more information about COVID and the brain that you can hear in Beth's full interview on our website.