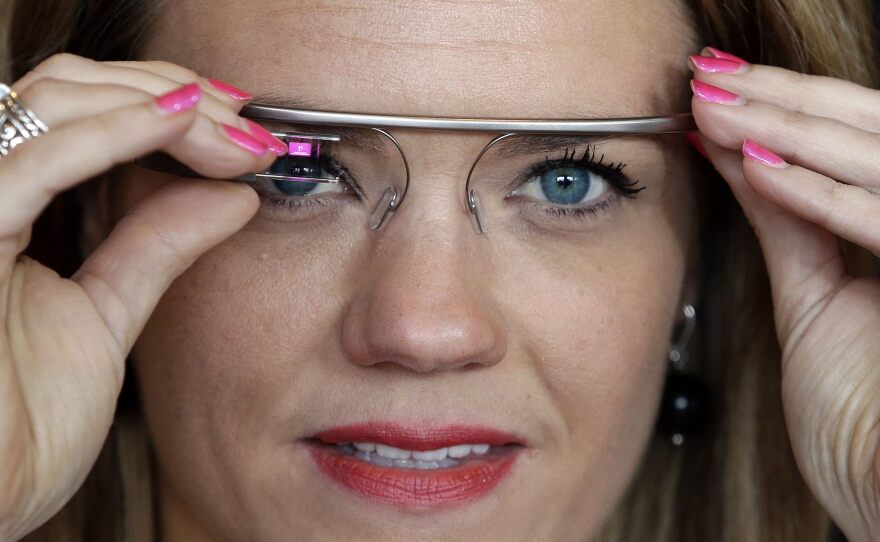

At Philz Coffee in Palo Alto, Calif., a kid who looks like he should still be in high school is sitting across from me. He's wearing Google Glass. As I stare into the device's cyborg eye, I'm waiting for its tiny screen to light up.

Then, I wait for a signal that Google Glass has recognized my face.

It isn't supposed to do that, but Stephen Balaban has hacked it.

"Essentially what I am building is an alternative operating system that runs on Glass but is not controlled by Google," he said.

Balaban wants to make it possible to do all sorts of things with Glass that Google's designers didn't have in mind.

One of the biggest fears about Google Glass is that the proliferation of these head-mounted computers equipped with intelligent cameras will fundamentally erode our privacy.

Google has tried to respond to these fears by designing Glass so it is obvious to the people around these devices when and how they are being used. For example, to take a picture with Google Glass, you need to issue a voice command or tap your temple before the screen lights up.

But hackers are proving it's possible to re-engineer Google Glass in any number of creative ways. And in the process, they've put Google in an awkward position. The company needs to embrace their creative talents if it hopes to build a software ecosystem around its new device that might one day attract millions of consumers. But at the same time, Google wants to try to rein in uses for Glass that could creep out the public or spook politicians who are already asking pointed questions about privacy.

So when Balaban first announced he had built an app that let folks use Glass for facial recognition, Google reacted harshly.

"I'd be lying if I said I was surprised," he said.

The company said it wouldn't support programs on Glass that made facial recognition possible -- and changed its terms of service to ban them. But that hasn't stopped techies like Balaban from building these services anyway.

And now, there are all sorts of things developers are doing with Glass that were not built into the original design.

Michael DiGiovanni created Winky -- a program that lets someone wearing Google Glass take a photo with a wink of an eye.

Marc Rogers, a principal security researcher at Lookout, realized he could hijack Glass if you could trick someone into taking a picture of a malicious QR code -- a kind of square-shaped bar code that can send a computer directly to a website.

But today, Rogers has nothing but praise for how Google responded to his hack. He says less than two weeks after he disclosed the problem to Google, the company had fixed it.

"The other thing that is really good is the way they pushed Google Glass out to a community of people who are particularly good at finding vulnerabilities and improving software and fixing software -- way before it is a consumer product," Rogers said. "This means that all of these vulnerabilities -- or at least most of them -- are going to be found long before Google Glass ever hits the market."

Google's decision to give the first few thousand pairs of Google Glass to tinkerers and hackers and geeks was intentional.

"In a case where you have [a product] that is so different from what is on the market currently, you really have to do these living laboratories where you figure out what the social and technical issues are before you release it more widely," said Thad Starner, a professor of computer science at Georgia Tech and a manager at Google Glass.

When Google released Glass to the public, it didn't sell it to just anyone. The first few thousand people who got a pair were developers, a technically sophisticated group whose first impulse was to take it apart, peer inside its code and understand how it works. These people are hackers at heart, and when they got their hands on Google Glass, they broke it on purpose, cracking it open and exploring all the ways it could be used or possibly abused.

"That's the great service our [Google Glass] explorers are doing for us," Starner said. "They are actually teaching us what these issues are and how we can address them."

But some of the issues raised by Google Glass might not be possible to address with a simple technical fix.

Ryan Calo, a law professor at the University of Washington who specializes in new technologies and privacy, has suggested that gadgets like Google Glass or civilian drones could act as "privacy catalysts" and spur conversations and legal debates about privacy in the digital age. Calo believes the conversations are long overdue.

Copyright 2013 NPR. To see more, visit www.npr.org.