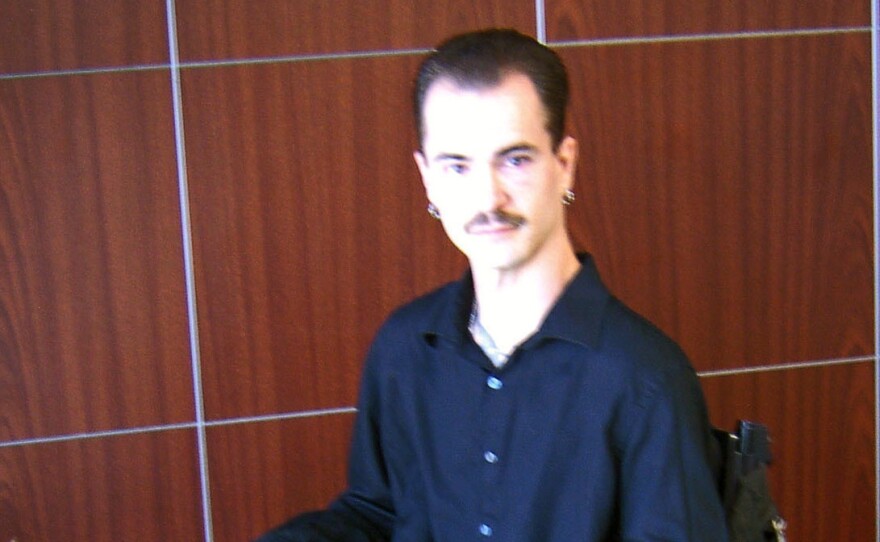

A car accident crushed Brandon Coats' upper spine when he was 16, leaving him unable to walk. His muscles still spasm, disrupting sleep and causing pain.

"If I'm out in public it's embarrassing," Coats says. "It's always uncomfortable. If I smoke marijuana, it almost completely alleviates it" — more, he says, than other prescriptions.

Coats smokes at night, and says he was never high when answering customer calls at Dish Network. "I was really good at my job," he says.

But five years ago, after he was called in by supervisors for a random drug test, he became persona non grata at the company.

"I went to open up the door and my card wouldn't open up the door anymore," Coats says.

It's been 25 years since the federal Drug-Free Workplace Act was passed, creating requirements for federal government workers and contractors. Many companies, including Dish Network, followed suit, and today more a third of private employers have drug-testing policies.

Although marijuana is now legal in two states and approved for medical use in nearly half, the drug policies of many companies haven't kept pace.

Coats has sued Dish Network over its marijuana policy; his case is now before the Colorado Supreme Court.

"We're not pushing for use at work," says Coats' attorney, Michael Evans. "We're pushing for, if you're in the privacy of your own home, you're registered with the state and abiding by the constitutional amendment, is that an OK reason for your employer to fire you?"

Since Evans sued Dish, Colorado has legalized pot, making it a regulated substance, like alcohol. But, as Evans notes, workplaces still treat pot — and test for its use — in a manner very different from alcohol.

"The test that Dish did was a saliva test," Evans says, "and all the test was concerned about was, 'Is THC present, yes or no?' "

And therein lies a problem. The standard urine test most commonly used in employer drug testing measures the presence of THC – a psychoactive compound in marijuana that persists in the body for days, weeks or even longer. So a positive marijuana test doesn't necessarily mean the person taking the test is high, or has even used the drug recently.

Barry Sample is director of science and technology for Quest Diagnostics, which conducts millions of drug tests. He says there may eventually be intoxication tests for pot that are more like the breathalyzer's detection of recent alcohol use. "It might be possible at some point, but it's still developing," he says.

For now, businesses are neither changing nor relaxing the way they test for pot. In a 2011 survey of major employers by the Society for Human Resource Management, more than half the companies responding said they conduct drug tests on all job candidates. And that raises some questions for businesses, says the society's Deborah Keary.

"If you had a martini on Saturday night, or smoked pot on Saturday night, but you're fine on Monday morning, how is Saturday night the employer's business?" Keary says. "So I really think they're going to have to change the way they do testing and define impairment."

And at least in Colorado, the legalization of pot is putting employers in even murkier legal territory.

Under state law, employers can prohibit use of marijuana at work. But another state law, the "Lawful Activities" statute, prohibits an employer from discharging an employee for engaging in lawful activity off the premises of the business during nonworking hours.

"And so that's where everything really gets muddied up," says Lara Makinen, legislative affairs director in Colorado for the Society for Human Resource Management. She says employers are getting a very mixed message.

"We're being told, 'Keep your policy as it is, but proceed with caution, because if people are fired, like Mr. Coats, we probably will see lawsuits,' " Makinen says.

Dish Network, the defendant in the Brandon Coats case, declined to comment. But the company has said it is sticking by its drug-free policy, which it says is consistent with federal law — law that still considers pot an illegal substance.

Oral arguments for Coat's case are set to begin in late September.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/