The illegal trade in ivory from African elephants has tripled in the past 15 years, to the extent that biologists fear for the creatures' future existence.

Most of the ivory is sold in China and Vietnam, and these days the U.S. government and international conservation groups urge those countries to arrest the traffickers. But for the better part of a century, from 1840 to around 1940, the U.S. was the world's biggest buyer of ivory. Hunters killed hundreds of thousands of elephants, and uncounted numbers of Africans were enslaved to carry the tusks to ships bound for America.

Most of that ivory went to a tiny town in Connecticut — a town that's now grappling with this dark part of its past.

Deep River is old New England, and its residents take their history seriously. Driving into town, I pass a fife and drum corps practicing for a performance on the village green. Stone barns from the 18th century, riverside mills and newly painted Victorian mansions line the highways.

People called Deep River "the queen of the valley" 150 years ago. Mills and factories and timber made the town well-to-do. But it was ivory that made Deep River rich.

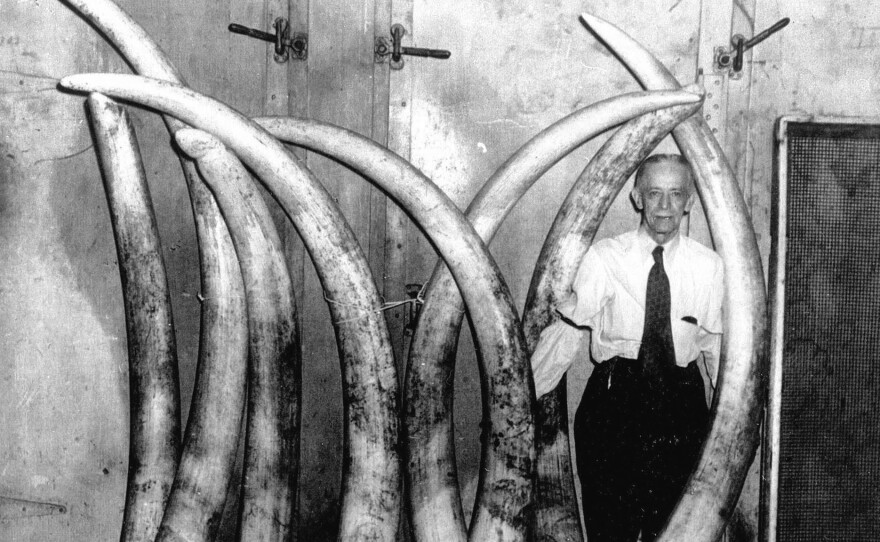

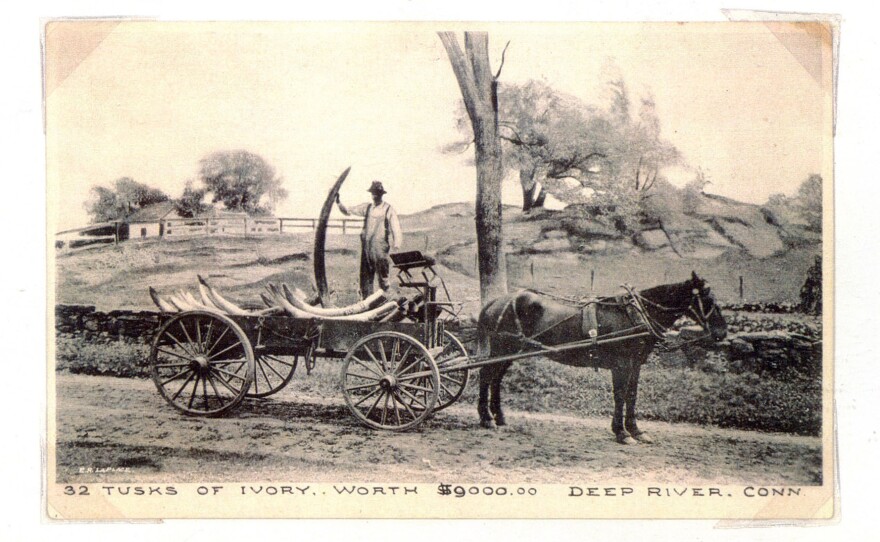

I travel up a road that winds from a landing on the Connecticut River into town, with Marta Daniels at the wheel. She's a freelance writer by trade, a historian by avocation. "I have always thought of this road as the road of tears," she says. Between 1840 and 1940, the wagons of Pratt, Read & Co. traveled this same route, carrying hundreds of thousands of elephant tusks from ships up to the company's factories and workshops. Pratt, Read was the biggest importer of ivory in the world at the time.

The big brick factory at the top of the road — it's longer than a city block — is now a condominium called Piano Works. Water still cascades through a nearby sluice that ran the factory's machines.

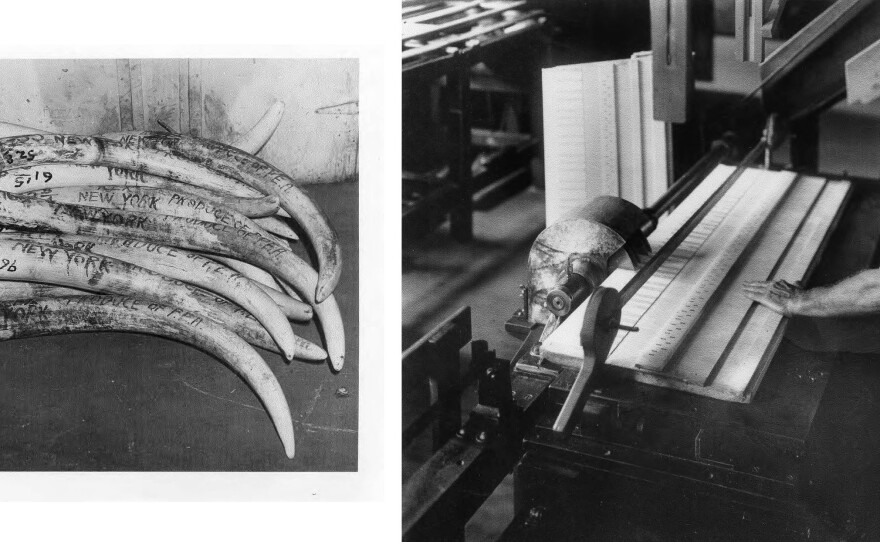

Jeff Hostetler, president of the Deep River Historical Society, says it was one machine in particular that brought ivory to this town and this factory. "What happened is Phineas Pratt, a very good mechanic and inventor, developed an ivory lathe to cut the teeth in ivory combs," he explains. "And, of course, all of Phineas' relatives bought one of Phineas' machines and went into the comb business."

And then into making billiard balls, cutlery handles, shirt buttons — all manner of ivory knickknacks.

Then came the piano. In the mid-1800s, a piano in the parlor became a symbol of middle-class cultivation. Pratt's efficient, mechanized cutting lathes were modified to make ivory piano keys. Piano keys required extra labor, and soon the business sprawled all over town. "Pianists liked white," Hostetler says of the piano keys. "So the way to get a good, uniform white color is to take these thin wafers of ivory and just bleach them in the sun."

Acres of bleaching houses sprang up — huge greenhouses containing blocks of ivory instead of plants. People fertilized gardens with ivory dust. Kids swimming in local ponds came out of the water coated in it. Soon, a rival company, Comstock, Cheney & Co., emerged and built a whole new town nearby for its workers, called Ivoryton.

The two towns dominated the piano key business for decades. Fortunes were made and spent on grand houses that still stand. One of them is now headquarters of the Deep River Historical Society and home to a startling assortment of the artifacts that made Deep River rich. Curator Rhonda Forristall shows me around. "You've got needles; you've got crochet hooks, toothpicks, buttonhooks," she says. Handles for straight razors. Buttons for corsets. For piano keys, the ivory was sliced thin, into laminates that were secured to wooden keys. "Three pieces go into making a key," she explains. "You could get 45 keyboards out of one tusk." Pianists liked the feel of ivory, and it wasn't until the 1950s that cheaper plastic keys completely replaced those made of ivory.

In Deep River, these artifacts are a source of civic pride, but pride that's also tinged with shame, especially as the world condemns the current slaughter of elephants to make trinkets. Daniels, for one, says if Americans are going to condemn others for trading in ivory, they should at least know their own history. "We were the largest importer of tusks anywhere in the world," she says passionately. "So we have a special responsibility and we have a unique opportunity to say, 'We are sorry we have done this, but we want in some way to help stop the slaughter now.' "

Citizens have formed the Deep River Elephant Tusk Force to publicize the ivory history here, both its good and bad sides. They organized a conference last year with speakers from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to talk about the U.S. ivory trade. They speak in schools, and they're lobbying for a law banning the import of existing ivory into the state. They raised money to buy an elephant statue that sits in front of the town hall.

Those efforts aren't likely to resonate in China and Vietnam. But Peter Howard, trustee of the historical society and a Tusk Force founder, says at least Deep River residents are now confronting the town's past.

"There's a lot of debt that's owed the elephant here," he says, "and a lot of awareness. But it was kind of in the back of peoples' minds."

Dick Smith — as first selectman of the town, he's essentially the mayor — says he knew about Deep River's ivory history, but not about the current trade in Asia. He says he'd tell ivory buyers now to stop, even though Americans once were just as guilty. "We learn from our experiences," he says. "It wasn't right."

Deep River's John Guy LaPlante is more sympathetic to the town's forebears. Attitudes were different 150 years ago. "You know, we deplore what happened to the elephant. It was brutal, there's no doubt about it. But we have to put it in context. These men ... who ran this industry, were upstanding, moral, high-minded people who didn't think they were doing anything wrong."

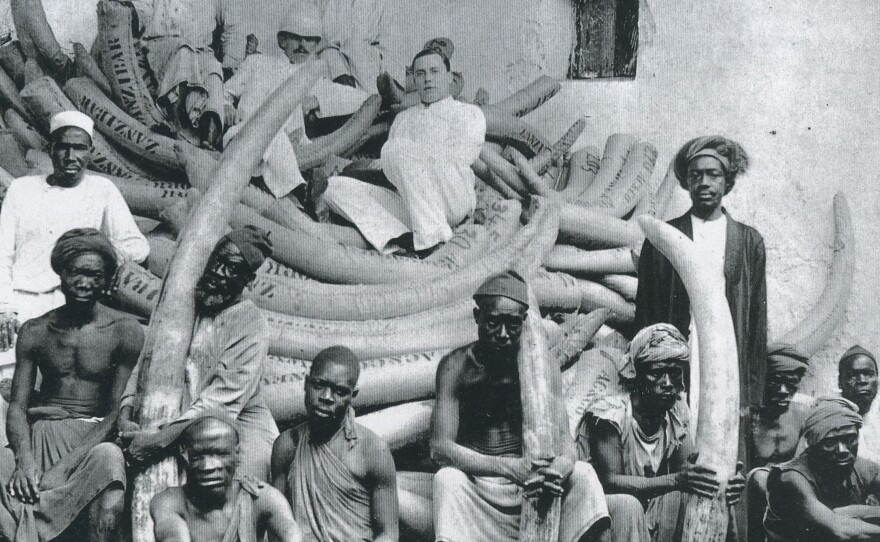

But there was another ugly fact about this trade that many Americans either didn't know about or simply chose not to see — ivory slavery. Ivory traders needed ivory bearers. So they captured Africans and enslaved them to transport the tusks to the ships.

Richard Conniff has investigated the African end of the trade. He's a writer who bought a house in Deep River and then discovered its past. He found historical accounts from Africa and from Deep River's ivory barons. They tell of ships from Connecticut that sailed to Zanzibar, an island off the east coast of Africa. Americans arrived with cloth, gunpowder and weapons to trade. The ivory came from central Africa, brought to Zanzibar by Arab slavers. "They would seize slaves, seize ivory, and then use the slaves to carry the ivory back to the coast," says Conniff. "And the descriptions that missionaries gave of those caravans were particularly brutal ... slaves bound by a log, basically, around the neck to the person behind them, and then carrying a tusk on one shoulder." Often, only 1 in 4 slaves survived the journey, according to British explorer Dr. David Livingstone, who observed and wrote about them.

One of the Connecticut buyers who sailed to Zanzibar was Ernst Moore, who worked for Pratt, Read. Moore spent years in the trade, and it made him wealthy, but he grew to hate it. He wrote a book called Ivory: Scourge of Africa. Yet, says Conniff, quoting Moore's book, "He is the one who also said, 'Our lives were so crammed with our business and adventure that we were perfectly content to take what we had and make the best of it.' "

Conniff, sitting in a gazebo on the Deep River landing where the ships once arrived with ivory from Africa, says that's likely the attitude of people who are buying illegal ivory now. "What they need to realize is what this town has discovered," he says, "that our involvement in that kind of thing is ultimately a source of shame, and that the grandchildren of those people who are buying that ivory are going to look at them with the kind of horror with which we now regard the ivory trade that happened here."

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.