Six months ago, we brought you the story of the Edna Karr High School marching band in New Orleans. Two members of the band in particular, snare drummer Charles Williams and tuba player Nicholas Nooks, or Big Nick as his friends call him, earned scholarships to Jackson State University in Mississippi — their dream.

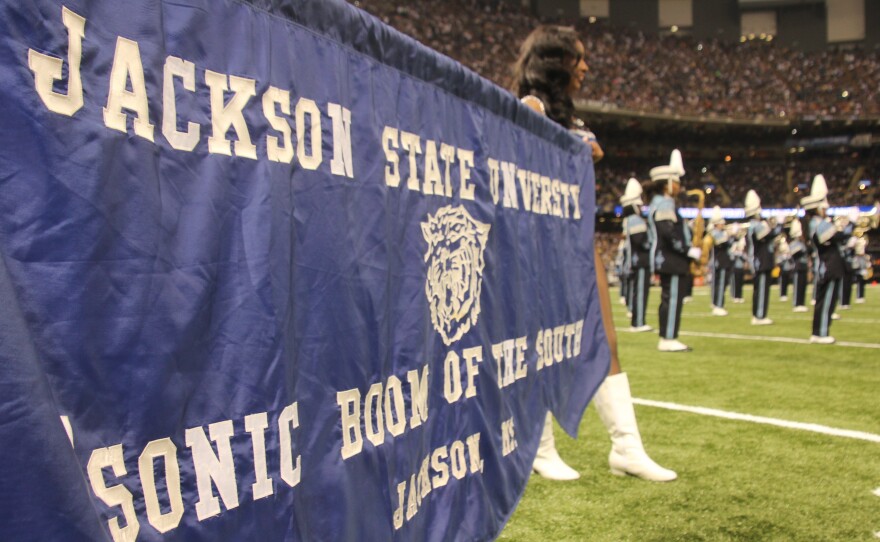

The marching band at Jackson State is known as the Sonic Boom of the South. Band camp began in August with 164 freshmen. But after weeks of late nights and early mornings, musical training and also push-ups, 24 had quit.

Williams and Nooks never considered leaving. They'd come too far, Nooks says, to give up now. Both of them come from single-parent homes with not a lot of money.

"A lot of people didn't think I could do it," Nooks says. "But I showed them that I could, and I'm here."

Band practice for the Sonic Boom begins almost every day at sundown and can last five hours. Students are penalized, even fined, if they miss practice.

"Do not expect to have a social life," says Dowell Taylor, director of bands at Jackson State. "It will not exist. If you try to have a social life, you are going to fail. So forget it now."

The Sonic Boom is more than just a band — it's Jackson State's most visible marketing tool. Only the best will make it.

Williams and Nooks understood the stakes from the beginning. As high school students last year, they prepared for their college auditions with the urgency of desperate men, seeking a way out of the poverty and violence in New Orleans.

"If you do good on your audition, that's like a lottery ticket," Williams says. "Basically you're winning money towards your education."

But unlike high school, Jackson State band members have to prove themselves every week in order to perform at football games on Saturdays.

"We do cuts," says Roderick Little, associate band director. "They have to play a solo that they've been working on throughout the week. And if they don't perform that solo correctly, then that simply means they don't make the cut for that week."

Nooks has impressed band directors so far. In September, he earned a spot on the field when the Sonic Boom played at a New Orleans Saints game.

But Williams didn't make the cut for the Superdome show or many other events this semester. Every Friday it went the same. He'd play his drum solo for Little, and he'd freeze up.

"He'll start off on the part, and then for some reason or another, he'll just totally just shut down and kind of give up," Little says.

And then things got worse for Williams. Despite his band scholarship and his financial aid, Williams still owed the university $5,800. And at the same time, he didn't have the money to pay his cell phone bill or get his textbooks.

"I still don't have money for books," he says. "It's real hard right now. I want to stay here. But it's just too much money."

Williams was worried that he'd get kicked out of school and have to scramble for a ride back to New Orleans. His mother, a baker at a New Orleans casino, has three other children and no car.

But in late September, university officials allowed him to stay, giving Williams more time to try to work things out. They've handled cases like his before.

"We draw an enormous number of students to Jackson State University with the band," says Deborah Barnes, interim dean of the college of liberal arts.

"They've seen the band, and they want to be in the band," she says. "And all they know is, 'I want to come and be in the band,' sometimes not understanding that that band is attached to a university, and the way you stay in the band is that you stay in the university."

Some kids struggle with grades, others lack support, and some have no idea how to survive at college because they've never seen anyone do it before. Many drop out, Barnes says.

Williams was pretty sure he was headed in that direction, but then the university found funding to cover the gap he was facing.

All of his problems weren't solved. He still didn't have money to buy those textbooks. He was worried about his grades. And he had no idea, just yet, how he'd cobble together his tuition in the spring.

But he'd finish this semester at least. He'd make it till December. Forget about the band; Williams still had a chance at college and the life he was dreaming for himself.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.