The year was 1975. Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese as American troops and civilians were forced to evacuate the country. Ronald Reagan entered the presidential race against Gerald Ford. A show called Saturday Night Live debuted on NBC.

And Ricky Jackson, Wiley Bridgeman and his younger brother, Ronnie, were convicted of the murder of an Ohio salesman. Jackson and Ronnie Bridgeman were 17 and Wiley Bridgeman was 20.

Their arrest was based on the testimony of a 12-year-old boy, Edward Vernon, who told police he saw the young men flee the crime scene. The three were charged and put away for life. Ronnie Bridgeman, who later changed his name to Kwame Ajamu, got out on parole in 2003.

Last year, Vernon recanted his testimony and said he had made a false accusation under pressure from police.

"This case will be dismissed," the judge said. "You're going to be free to go. May I suggest to you that life is filled with small victories, and this is a big one."

'The Day My Life Stopped'

The three men's story begins on May 17, 1975.

"That was the day my life stopped, so that day is in my mind forever," Jackson says.

"Yeah," agrees Ajamu. "I remember that day as if it was just five minutes ago."

"At the time of the crime, I was in my driveway washing my car," Bridgeman says. "Afternoon time, nothing to do. Just a normal day."

A normal day that turned into anything but. Jackson and Bridgeman were walking in the neighborhood when they started hearing people talk about a crime.

"There was a robbery up there, and somebody had killed a gentleman and shot the store owner," Jackson says. "Unbeknownst to us, somebody was actually saying that we were the perpetrators. Ronnie Bridgeman, Wiley Bridgeman and myself."

They were arrested and taken downtown, charged with murder and put in prison to await trial.

"I thought that this was just a mistake, and that they would get this straightened out and we would be out of here within a day or two," Jackson says, "because everybody was reassuring me — my mother, my parents — that this was going to be over, it was just a mistake. But it didn't turn out that way."

This is how Bridgeman remembers it:

"No, I didn't expect to be in jail longer than a couple of days myself," he says. "Maybe they have a lineup, maybe they check their records or whatever they do, and we'd be dismissed."

That didn't happen. The testimony of one young boy was enough to sentence them to death.

Jackson says that the prosecutors tried to get them to take a plea deal to save their lives. They refused.

"You know that was the only thing we had to hold onto was our innocence," Jackson says. "And if we gave that up, then the game was over. So we had to hold onto that."

Learning To Live With Little Hope

Ultimately, their death sentence was lifted when the Supreme Court overturned Ohio's capital punishment law in 1978. Instead, they were sentenced to life in prison for a crime they insisted they did not commit.

Weeks turned into months, months turned into decades, and each man found his own coping mechanism in prison. For Jackson, it was gardening.

"I had a greenhouse," he says. Jackson grew mostly vegetables, but also flowers to sell to corrections officers. "I came in as a student and I left as a manager."

When he wasn't in the greenhouse, he was reading.

"I finally read Catcher in the Rye, finally, before I left prison," Jackson says. "I wanted to know what the big deal was about that book. And honestly, I didn't get it. But I just read stuff like that, because that was my form of coping and my form of escape. You know, books took me everywhere."

Bridgeman escaped through books too — especially poetry.

"Like Robert Frost. I read a lot of his work," he says. "I did some Edgar Allen Poe, like 'The Raven.' That was really something. I think poetry really talked to the spirit."

Ajamu says he took every opportunity to try to learn something, anything.

"I also was able to work my way into the vocational culinary," he says. "I can really cook. I can barbeque. I can do any kinds of food you like."

Over the years, each man had to maintain a delicate balance, staying hopeful, believing that one day they'd be released — but keeping those same expectations in check.

"In the prison environment, that's the last thing you want to do is get too hopeful about anything, because nine times out of 10 you're going to get more disappointment than positive results," Jackson says. "And letdowns are magnified tenfold in prison."

Finally, Freedom

Then, in 2003, Ajamu, the youngest of the three, was granted parole.

"When they called my name, I went up front to the desk where the officers were at," he says. "They said, 'Hey man, it's been fun, but you got to run.' "

The prison guards gave him some clothes and the belongings he had with him when he was arrested 28 years ago. He left the prison gates.

"And I just took off," he remembers, laughing. "And when I stepped on the other side of that fence, I did a little jig that I promised myself I would do if I ever lived to be released from prison. I did a little jig, like you see Bruce Willis do in Die Hard."

But he never stopped thinking about Jackson and his brother, still locked away. For the next 10 years, he worked to get them released.

Then, in 2013, the entire case against the men disintegrated. The young boy who testified against them, Edward Vernon, recanted his testimony, saying he had been a scared kid, intimidated and pressured by police, and that he made up the whole story.

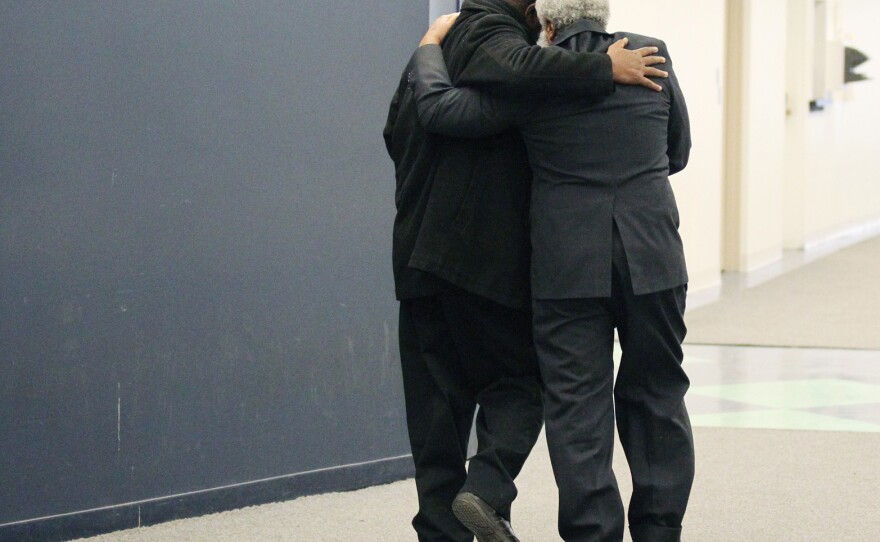

Roughly a year later, Jackson and Bridgeman were freed.

Brothers Reunited

When they got out, one of the first things Jackson wanted to do was eat at a nice restaurant.

"Red Lobster, as a matter of fact," he says. "A lot of seafood. I think I ate a little too much, though, because I barfed back in the hotel room. It was a good barf, though, probably one of my best."

The Bridgeman brothers were finally reunited. A photographer captured the moment. The younger brother is pulling on his older brother's beard. Ajamu says there's a story behind that gesture that goes back to childhood, when he was 6 and his brother 9.

"We were playing King of the Hill or something, I can't remember," Ajamu says. "But I remember my brother said, 'When I get old, I'm going to have a big white beard like Moses or Santa Claus.' I was like, 'Ah, you ain't going to have no beard like that.'

"So when, that day, when that door opens and my brother came out with that white beard, it just crushed my heart," he says. "So I touched his beard and I asked him if he remembered it, up close, just he and I. And he said, 'Sure.' And so that's why I cried."

Anger Long Past, A Time For Healing Begins

Jackson says he holds no anger towards Vernon. After Vernon finally told the truth in court, Jackson says he locked eyes with him.

"I basically just nodded to him and mouthed the word 'Thank you' to him, because he was made a victim like we were," Jackson says. "They took advantage of a 12-year-old kid."

Being angry won't solve anything, he says.

"I'm trying to heal myself," he says. "Hopefully he can heal himself. And this is a part of healing, to forgive him so I can move on with my life."

The Bridgeman brothers agree. Too much time has been wasted already, they say.

"I was mad at Edward Vernon for about a week, because we were kids," Ajamu says. "But that's the whole thing: We were kids. We were children."

Almost 40 years later, they are men on the verge of old age. They are grey, they are tired but they are free — and they are together.

"My brother, we call him Buddy," Ajamu says. "My brother's my first best friend. My hero. My everything."

The state of Ohio has a fund set up to compensate prisoners who served time after being wrongfully accused. The attorneys for both Bridgeman and Jackson say their clients will submit a claim in hopes of getting some financial help from that fund, but the process could be long and complicated.

Bridgeman's lawyer says in the worst-case scenario, the entire case would need to be re-tried.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.