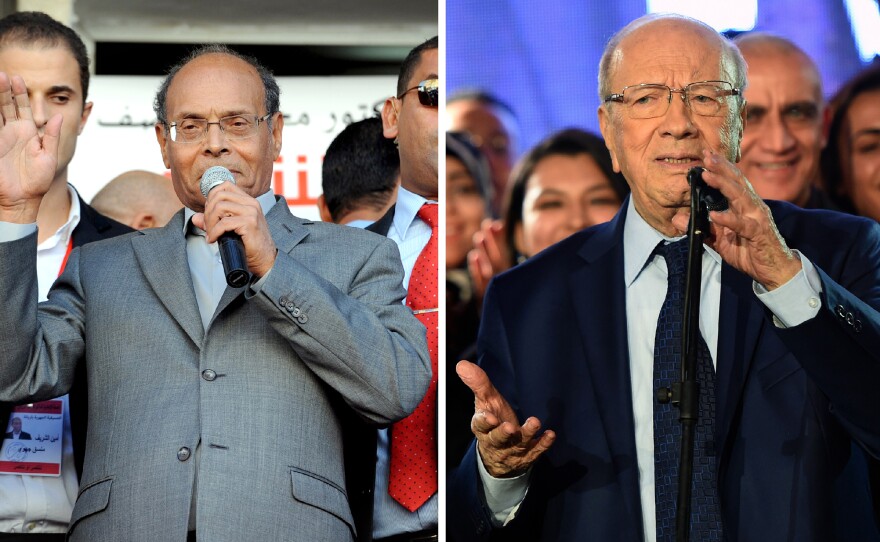

The main boulevard in the capital Tunis is alive with political debate about the two candidates for president in this Sunday's election. In one tent, campaign workers play music and hand out fliers for Beji Caid Essebsi, an 88-year-old candidate who held posts in the old regime and then served as an interim prime minister after the country's revolution in 2011.

In another tent just down the road, patriotic music plays for Moncef Marzouki, a former human rights activist who has held the job of president for three years on an interim basis while the new constitution was written.

Tunisia stands out in a region roiling in violence, chaos and the resurgence of despotism. If there is a democratic handoff for the head of state, it will mark the most peaceful transition of power born from the wave of revolts that swept through the Middle East in 2011. The race is close. And the choice is being cast as a vote between a soft version of the old regime, represented by Essebsi, and a disheveled populist, Marzouki, who draws power from an Islamist base. A major reason that a peaceful transition is possible in Tunisia is that the Islamists didn't seek to dominate when they came to power. "The best way to describe the Tunisian experience is the experience of consensus and not the experience of conflict," says Rachid al-Ghannouchi, a founders of Tunisia's most powerful Islamist movement, Ennahda. He says his party wanted to avoid polarizing the populous like the Muslim Brotherhood did in Egypt. There, the Brotherhood came to power in 2012 but were thrown out in a military coup a year later that has included a violent crackdown against the group. So Ghannouchi's party agreed to dissolve the cabinet that it controlled. And to avoid conflict between secularists and Islamists, it didn't put forward a presidential candidate. Ghannouchi says that in the long run, it's wise politics. "For us, the success of the democratic experience is more important than our party's interests," he says. "Allowing the democratic experience to survive, even with a man from the old regime, will allow us the chance to come back to power in the future. But if the experience fails, then everything will fail and we will enter the world of terrorism and chaos." That chaos is visible throughout the region. Next door in Libya, two rival governments and their militias are wreaking havoc. Syria's in a civil war and Yemen is on the brink of collapse. "Tunisia is the standing tree in a collapsing forest from here to Iraq," says Ghannouchi.

That desire to remain standing is what makes this election significant.

In downtown Tunis, Mohamed Nasr says he's voting for Essebsi. "It's decisive, it's going to be a turning point that will save the country," claims Nasr. He thinks Marzouki and the Islamists elected to the legislature in 2011 hurt the economy and fostered extremism in Tunisia. Nearby, a woman named Leila speaks up. My brother was tortured and imprisoned for being an Islamist under the old regime, she says. The government that Essebsi served did that to him. That's why she's voting for Marzouki. But she won't give her full name, she says. She's afraid that with the shift of power, the Islamists could be targeted again.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.