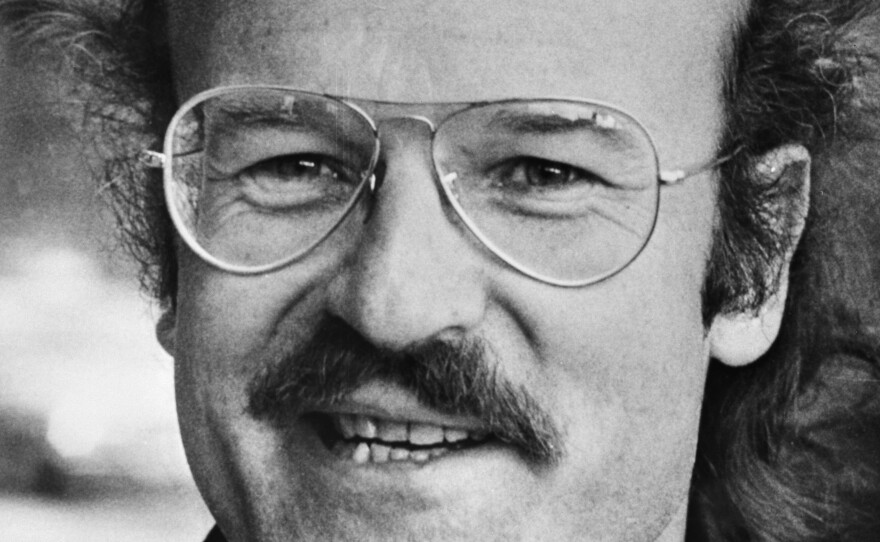

Günter Grass wrote more than 30 plays, novels, books of poems, essays and memoirs. He was also a visual artist and sculptor. He won the 1999 Nobel Prize in Literature. He died of undisclosed causes in the German town of Lübeck, his publisher, Steidl Verlag, confirmed. He was 87 years old.

Grass was best known for his first novel, The Tin Drum, and for the secret he kept for half a century: Grass was 6 years old when Hitler came to power and the Germans took control of his hometown, the Free City of Danzig — today, Gdańsk, Poland. Four years later, Grass joined The Hitler Youth Movement, as he told WHYY's Fresh Air in 1992.

"It was marvelous for [a] 10-years-old boy to go with this group," he said. "There was a tent, and with a flag, and playing Boy Scouts like this. It wasn't political at all in the beginning. It became more and more political. It was really successful propaganda done by the Nazis."

Grass volunteered for the submarine service, but was drafted into a tank unit.

"I became a soldier when I was 16, the last year of the war," he recalls. By the time he was 17 "the war was over, and I was in an American prison camp — a prisoner of war. And slowly, slowly I discovered what really has happened. And [in] the beginning I didn't believe — I thought it was propaganda what they were telling us. It's not possible the German people has done this."

Grass said he only understood the truth when the Nazi War Criminals were tried at Neuremberg. "I listened to the radio, and I heard my former Youth Leader ... And he said yes, it's true. It's terrible. But from this moment on, it was clear for me what has happened. And this knowledge never left me."

Trying to come to terms with that knowledge is the basis for much of his writing, says Siegfried Mews a Günter Grass scholar, and Professor Emeritus of German at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

"He has produced works which were not necessarily eagerly welcomed," Mews says. "That is true, for instance, of his first big novel, The Tin Drum, but you can't just ignore it."

The Tin Drum is the story of a Danzig boy, Oskar, who gets a tin drum for his third birthday, then decides to protest the Nazi rule by never growing up. As an eternal child, Oskar witnesses an adult world that is chaotic and cruel, with synagogues set on fire, and fierce fighting between Germans and Poles. It became an Oscar winning film by German Director Volker Schlöndorff.

After his initial success with The Tin Drum, Grass went on to write dozens of plays, memoirs, poems and novels — including fable-like tales called The Flounder, The Rat and The Call of the Toad — a comic romance between a German widower and Polish widow in the city of Gdańsk.

Grass became known as the conscience of Germany, a liberal who engaged in politics and spoke his mind. When the Berlin Wall came down, Grass argued against reunification, saying a united Germany could once again become a war-mongering state.

But then, in 2006, Grass finally admitted that his service at the end of World War II was with the Waffen-SS — the combat unit of the Nazi Party's elite military police force. Mews says the revelation exposed Grass as a hypocrite.

"When President Reagan visited the Federal Republic in the late '80s," Mews explains, "he and Chancellor [Helmut] Kohl visited the cemetery — and there were graves of Waffen-SS members. And Grass condemned this act without mentioning that he himself might have been one of those who were lying there in the cemetery."

Mews says Grass never adequately explained why he kept his service in the Waffen-SS a secret. "He should have said it earlier," Mews says. "But on the other hand, I don't think it invalidates his work, his fiction. And his dramas and his activities in the service of building a better, a more democratic Germany after the war."

It took Grass 60 years to confront his own role in the Nazi army. But at a New York Public Library event in 2007, Grass said when he became a writer, he knew right away he had to confront the sins of his country.

"I had to write about my time, what has happened to my generation, what has happened to my country," he says. "I was confronted. There was no way out."

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.