On Tuesday, the MacArthur Foundation awarded 33-year-old photographer and video artist LaToya Ruby Frazier a MacArthur Genius Grant. Frazier's work is set in Braddock, Pa., the small town outside Pittsburgh where she grew up. Built on steel, today Braddock is struggling to get by. Frazier tells NPR's Ari Shapiro why she chose to focus her lens on her hometown.

Interview Highlights

On why she chose Braddock as her subject

There's a large African-American history in our contribution to the town and the steel industry that has been overlooked and ignored and erased from the history pages. ... I got a book [from the library] ... and I turned through that book and by the time I got to the end of it, I realized that all African-Americans had been omitted from the history. ...

All the questions — you know, wanting to understand, you know, why did I live in this dilapidated house with my grandmother on this shrinking street? ... I would come out [of] that house and the first thing I would see is the railroad tracks and then to my left is the steel mill hovering over me, and this area was known as "The Bottom." And because I had so many questions about my displacement and my plight and the disenfranchisement we were facing, I turned to the camera to try to get a little bit of distance to really look at it and understand head-on what was actually occurring. Like, what was the crisis that was affecting my family socially, economically and politically? And the only way I knew how to do that was through the visual arts.

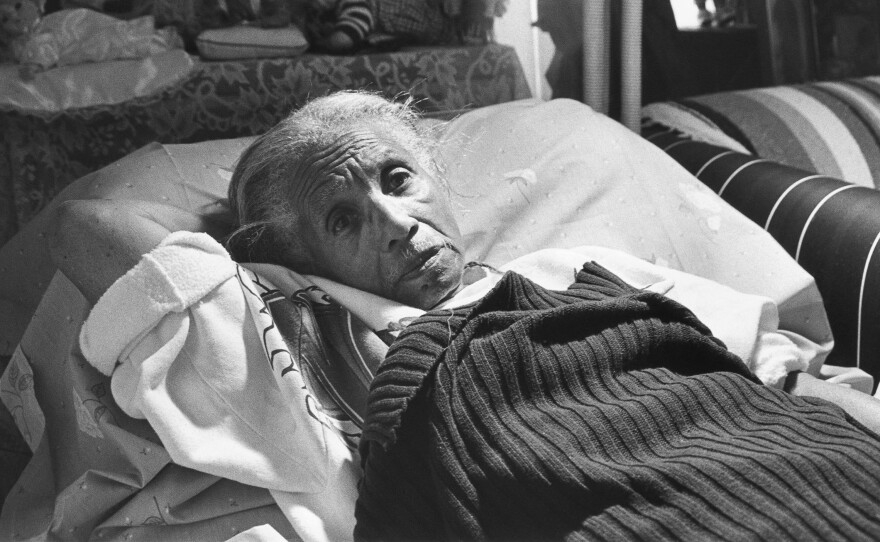

On why she chose to focus so much on her own family

I'm retelling the history of Braddock and the collapse of the steel industry and the subsequent 30 years of disinvestment through the bodies and the perspective[s] and voices of my grandmother Ruby, my mother and myself. And my grandmother grew up in Braddock in the '30s and the '40s, when it was prosperous and a melting pot — a city. And my mother grew up there in the '50s and the '60s during segregation and the beginning of white flight and the start of the collapse of the steel industry. And I grew up there in the '80s, once the steel mills had downsized and they began to demolish them. And so because this type of narrative and perspective has never been told or seen, I felt obliged to, you know, use my camera to document what was actually happening to us.

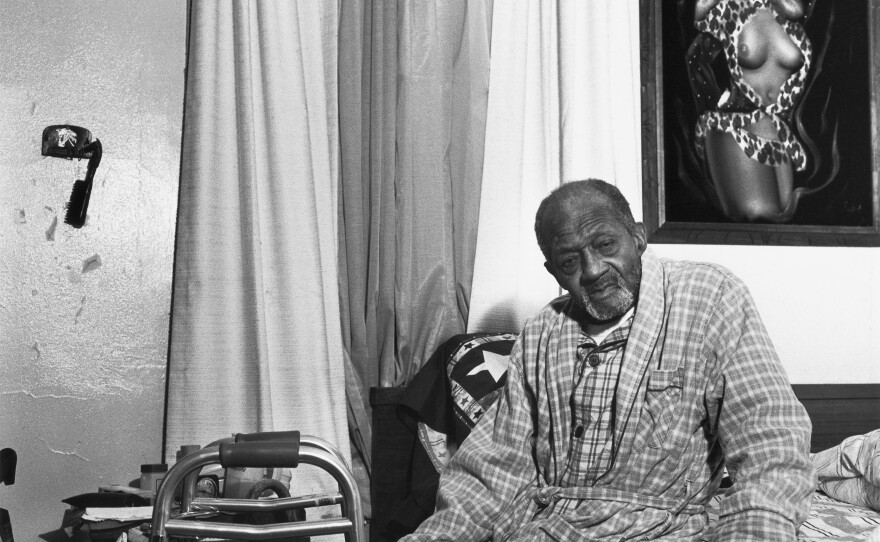

On a particularly intimate photo she took of her grandmother in her recliner

It was just one of those powerful, stoic, transcending moments. My grandmother Ruby was a woman of very few words, was very serious, didn't like to talk about the past. ... So I'm leaning over her, she's in her recliner. She really didn't like me to make photographs, she only cooperated on maybe five or six, and this was one of them. And so it's a Saturday afternoon where I'm leaning over her with my 35 mm camera and we just pause and she actually looks into the lens, but she's really looking, gazing through the lens directly at me, almost like she's transferring some type of history without speaking a word. And as she looks at me intensely with that pensive stare, I clicked the shutter.

On whether it makes her feel powerless to document a crisis she can't change

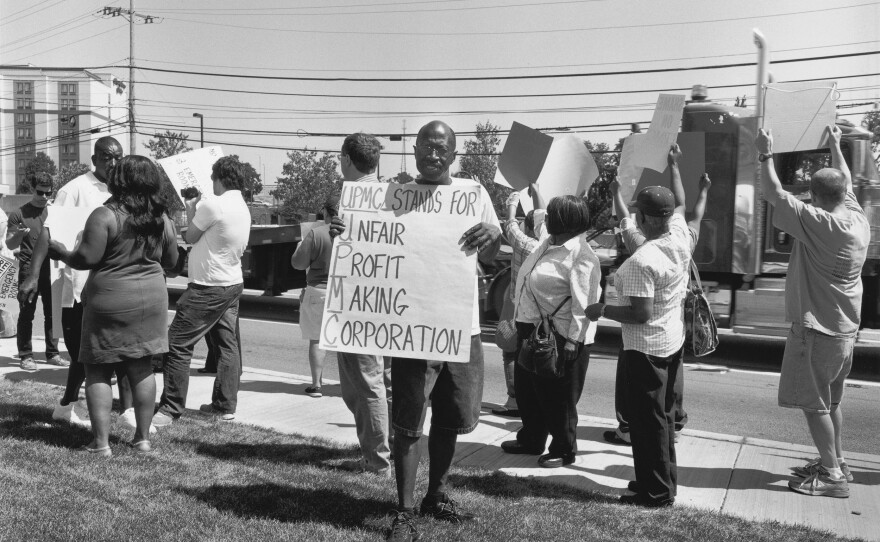

I actually feel the opposite. I feel very empowered by it because when you can take a strong look at a crisis head-on and be able to understand all the different layers of how this is stratified and how it's structured, it helps you to deal with the loss and the struggle and the pain. And it also helps you to create a human document, an archive, an evidence of inequity, of injustice, of things that have been done to working-class people. It's a testament, you know; this is my testimony and call for social justice. And it's also a way of me writing people who were kept out of history into history and making us a part of that narrative, making us a part of Andrew Carnegie's story and the story of the steel industry.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.