Limacina helicina looks like most any other sea snail — until it beats what look like delicate wings and "flies" through the water.

A newly published study in the Journal of Experimental Biology says the tiny species of sea snail moves through water using the same kind of motion that an insect uses to fly.

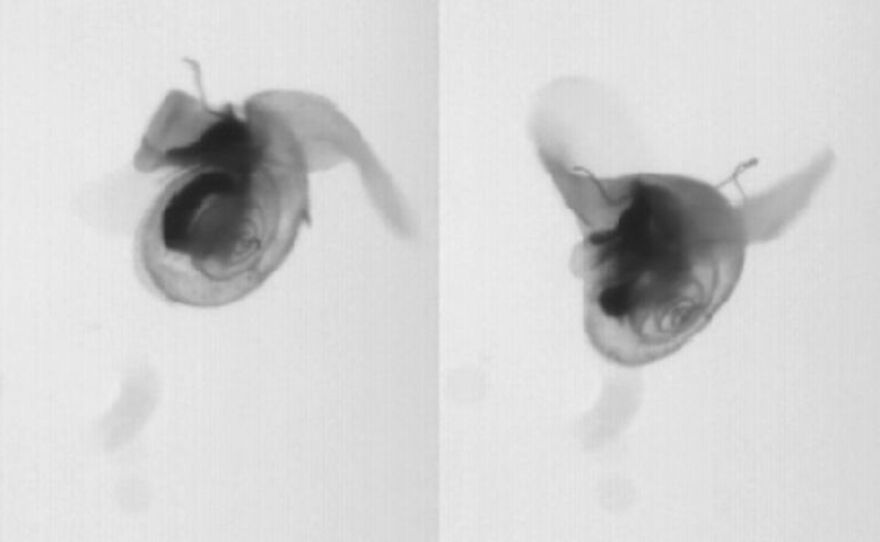

Take a look at the "sea butterfly" in action:

It's "a remarkable example of convergent evolution," the researchers write. They say the ancestors of zooplankton (such as L. helicina) and those of flying insects diverged some 550 million years ago.

This sea snail's movements are more like a fruit fly's than other zooplankton, the study found.

L. helicina, which lives in cold Pacific waters, has two smooth swimming appendages "that flap in a complex three-dimensional stroke pattern resembling the wingbeat kinematics of flying insects."

Other types of zooplankton typically "paddle through the water with drag-based propulsion" rather than fly, the researchers say.

Study co-author David Murphy tells the Journal of Experimental Biology that the sea snail and fruit fly both "clap their wings together at the top of a wing beat before peeling them apart, sucking fluid into the V-shaped gap between the wings to create low-pressure vortices at the wing tips that generate lift."

The scientists say flying instead of paddling gives L. helicina an advantage. "The potential benefit ... is that flapping appendages are more mechanically efficient than rowing appendages at all swimming speeds," according to the study.

Close observation of the snail's movement was possible because of a "new 3D system to visualise fluid movements around minute animals," built by Murphy.

The tiny creatures were caught in Oregon and transported to Atlanta for study.

"It really surprised me that sea butterflies turned out to be honorary insects," Murphy says.

Additionally, the sea butterflies "can play a big ecological role," the BBC reports. "The nightly migration of zooplankton, like Limacina helicina, to the ocean surface to feed and escape being eaten, is one of the biggest movements of biomass on the planet."

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.