Who, exactly, is a martyr? That seemingly simple question is behind a controversial new exhibit by artists in Denmark that's ignited a fierce debate.

Even before the May 26 opening of the exhibit, called the Martyr Museum, critics claimed it endorsed terrorism and Denmark's culture minister, Bertel Haarder, described it as "crazy."

The controversy centers around the depiction of historic figures like Socrates and Joan of Arc near modern-day suicide bombers.

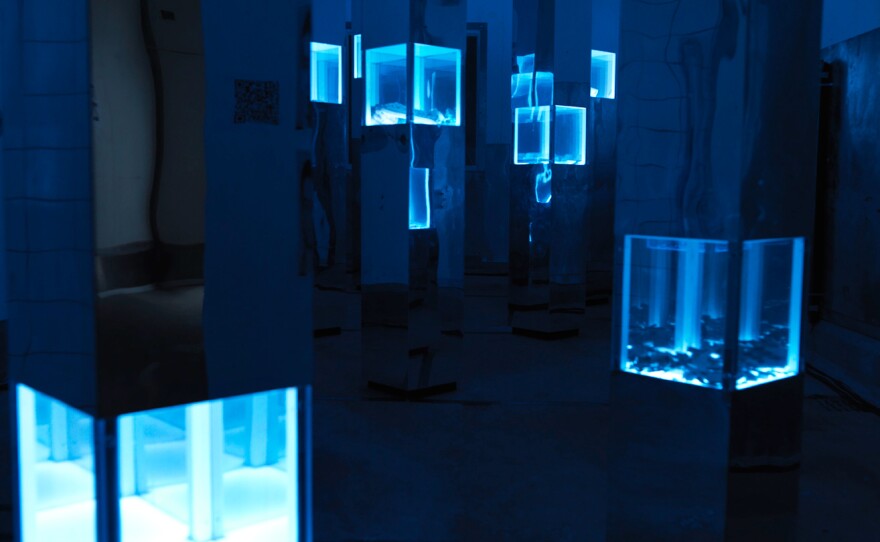

The exhibit is tucked away in a former slaughterhouse behind Copenhagen's central train station. Its white-tiled walls are lined with portraits and "reconstructed artifacts" like the vial of poison that Socrates drank after he was sentenced to death and the podium where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech.

But it's during the twice-a-day guided tour, led by actor Morten Hee Andersen, that the space comes to life with music and stage lighting.

In one section, visitors are shut in a meat locker as the guide falls to the floor to tell the story of Maximilian Kolbe, a Franciscan friar who voluntarily took the place of Jews the Nazis condemned to starve to death at the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II.

Further along, the guide assumes a lotus position and, with trembling hands, recounts the 1963 self-immolation of Thich Quang Duc, who took his life to protest the treatment of Buddhists in South Vietnam. Photos of that event shocked the world at a time when the U.S. was becoming involved in the Vietnam War.

And finally, there's the section most responsible for the headlines: a room where the reconstructed artifacts flashing under strobe lights hit a little closer to home.

A melted keyboard from Ground Zero of the Sept. 11 attacks in New York. A portrait of Mohammed Atta, one of the men who carried out that attack.

There are also portraits of the two brothers, Ibrahim el-Bakraoui, who blew himself up in March at the Brussels airport, and Khalid el-Bakraoui, who blew himself up at a subway station an hour later. There is a crumpled coffee cup from the airport, and a display of nails that were used as shrapnel in the attack.

It's here, among these manufactured artifacts, that the guide recounts the speech on good and evil reportedly delivered by Omar Ismail Mostefai to his hostages in the midst of the attack that left more than 100 dead in Paris last November.

Critics call this provocation for the sake of ticket sales.

Not so, says artist Henrik Grimbäck.

"Since 9/11, the word 'martyr' has been popping up in our minds more and more. It would have been in many ways strange if we were not discussing our own time when we did this show," Grimbäck says.

The show does not endorse such actions, but seeks to explore the many definitions of the word "martyr," says fellow artist Ida Grarup.

"To see the world through these terrorist eyes for a couple of minutes is not the same as sympathizing or understanding them," Grarup says.

Not everyone agrees.

"I don't like relativism. I think they are relativists," says Alex Ahrendtsen, spokesman on culture for the right-wing Danish People's Party. "If you're a Westerner, you have to take a stance. You have to say, well, you might say that Islam has martyrs. But we don't think they're martyrs – they're murderers. They're terrorists."

The artists have noted that some of their most vocal critics are the same people who staunchly defended the Danish newspapers that published inflammatory cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad a decade ago.

"A lot of Danes feel like freedom of speech is a very big thing, and they like to talk about it. But when it's something that they don't necessarily agree with, then it's not freedom of speech, it's just wrong," says sociology student Tea Ingemann Olsen, who traveled two hours to see the Martyr Museum.

But in a country with a very strong tradition of free speech, very few critics have actually suggested that the exhibit be shut down.

"It's an ignorant, stupid exhibition without any deeper knowledge. But they have the right to do it," says Ahrendtsen, the Danish People's Party spokesman. "If I don't like it, I don't have to go."

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.