What happens when two human political journalists compete against a computer over which can do the best job predicting the issues that will dominate the news in the presidential election? Well, you are about to find out.

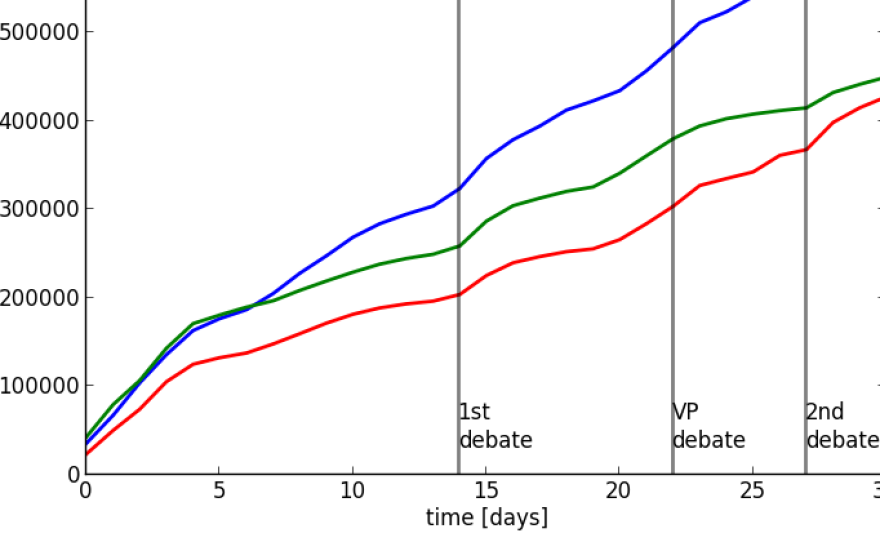

The two humans and the computers each got to predict five issues per presidential candidate that would get the most coverage in the news and on the blogs between Sept. 12 and Oct. 12. (The time frame covers only a few days of the release of Donald Trump's vulgar comments about women. So the final list isn't dominated by that controversy.)

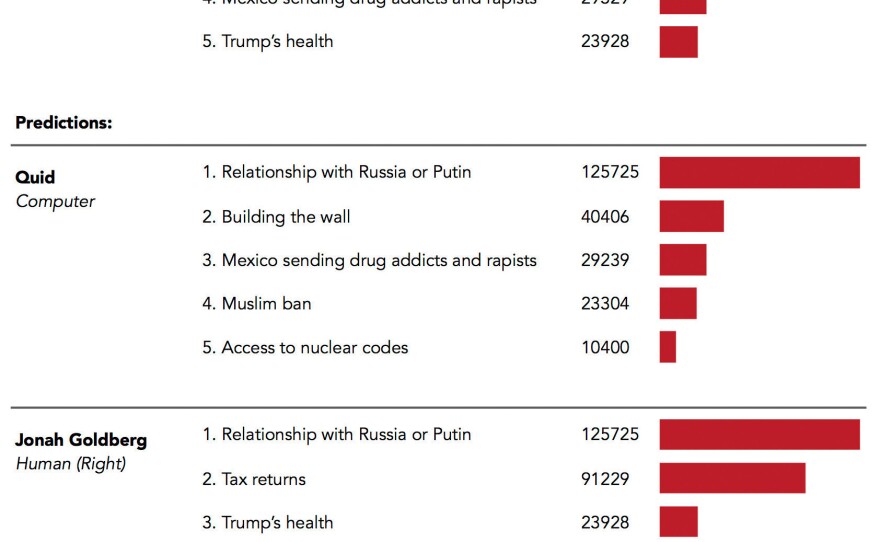

The two humans are Simon Maloy of Salon.com and Jonah Goldberg of the National Review. The computer is a program designed by the digital analytics firm Quid. The list of their top five predictions is below.

And what a difference a month makes. Goldberg had expected a lot more discussion of Trump's tax returns and expected that Clinton would make a big mistake at the debate. "I think it would be inappropriately laughing at something she shouldn't laugh at," Goldberg had suggested.

Maloy had thought Trump would say something sexist about Clinton and that there would be intense coverage of her health status after she made her first comments on the topic.

The computer program predicted a lot of coverage of Trump's talk of building a wall along the Mexican border. And it forecast that Clinton would continue to face scrutiny over her email.

Actually the computer was wrong: By volume of coverage the No. 1 issue that plagued Clinton was her health, giving Maloy the edge. "Simon was actually winning the first five days," says Dan Buczaczer of Quid.

But the contest wasn't about just one prediction. And when all five predictions are taken into account ... well, that's one more blow to the superiority of humanity; the computer won.

That means it gets a free NPR T-shirt, as promised. They still have to let us know what size.

The computer's victory came despite a whole lot about the last month that was not predictable — Trump's attacks on Miss Universe, and the leaked NBC tape.

Though Maloy predicted Trump would say something sexist about Clinton, while Trump did face accusations of sexism, they were not for things he said about her.

Buczaczer says the computer picked up on a general trend of sexist comments but didn't think that was enough to make a detailed prediction.

"So we'd seen a lot of information about controversies between Trump and women," Buczaczer says. "But we did not realize that there was a tape on a bus with Billy Bush that was about to be released."

Ultimately, the contest was judged by whose predictions got the most coverage by news media and blogs. Both humans got some things totally wrong. The computer did better.

Buczacer says the computer has an edge because it can take a historic look and map out the trends. It can see which issues keep coming back, suggesting they'd continue to get coverage in the press, Buczaczer says. "And they allowed us to make what I would call some safer picks because we had that background and that knowledge."

In fact, being too swayed by what's in the media at a particular moment may be one of the reasons that political pundits are especially bad at predictions, says Dan Gardner, co-author of Superforecasting: The Art And Science of Prediction.

"The pundit on TV doesn't have only an interest in making an accurate forecast," he says, "that pundit has an interest in making an entertaining forecast, or a forecast that will attract attention."

Gardner says that the best human forecasters are the ones who bring a lot of curiosity and humility to the process.

Or, maybe pundits can team up with a computer.

Buczaczer says that is actually how Quid's data are meant to be used. "If Jonah or Simon want to come in, look at something through the lens of Quid and then filter it through their expertise, it becomes even that much more powerful," Buczaczer says. "It's really that combination."

And at a time when analytics and big data are being used to predict all kinds of things, Buczaczer and others think it's important to remember: Computers help expand the human mind. They don't replace it.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.