As the six-week trial of Ammon Bundy and his co-defendants wound its way to Thursday's startling conclusion, Bundy's supporters were a colorful presence outside the federal courthouse in Portland, Ore.

They dressed in traditional cowboy attire and waved American flags at passing cars. Some even rode horses up and down the busy city sidewalk.

A block away, Jarvis Kennedy watched all of this and rolled his eyes.

"We don't claim to be victims, but we were," he said.

Kennedy is a councilman with the Burns Paiute Tribe in Harney County, Ore. That's the home of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, which armed militants — led by brothers Ammon and Ryan Bundy — occupied in protest of the government's ownership of federal lands.

Kennedy was also on the street anxiously awaiting a verdict. When it came, all seven defendants were acquitted of conspiring to impede federal workers from doing their jobs.

But the Bundy family's mostly white, anti-government movement has had an unintended effect: It has refocused attention on the ancestral rights Native Americans hold to lands across the Western half of the United States.

"They didn't know what they were getting into, they didn't do their homework," Kennedy said before the verdict.

"I was raised like this to know that it's always going to be our land — no matter who owns it, it's always going to be us," Kennedy said. "We're the first people, and when everything's done and said, we're going to still be there."

When the occupiers took over the refuge last January, the Burns Paiute people watched in dismay. Ancient artifacts stored there were handled and moved. At one point the militants bulldozed through sacred burial grounds while trying to build a road.

Long before it became a refuge in 1908, the Malheur was the traditional winter gathering area for Kennedy's people. That was also long before they were moved to a 10-acre reservation near a landfill outside the small town of Burns.

Kennedy's tribe briefly made national headlines when it spoke out during the occupation. Tribes from around the country and First Nations people in Canada called with offers to come to Burns and support them. Kennedy says his tribe declined. It was just too tense of a time and they were worried about violence.

But in the end, he says something good came out of it all.

"As Native peoples, this Bundy stuff kind of kicked off something, like a unity thing," Kennedy said.

Tribes in Nevada are now pushing for permanent protection of lands they consider sacred around militia leader Cliven Bundy's ranch, the man who inspired the Oregon occupation and father of Ammon and Ryan.

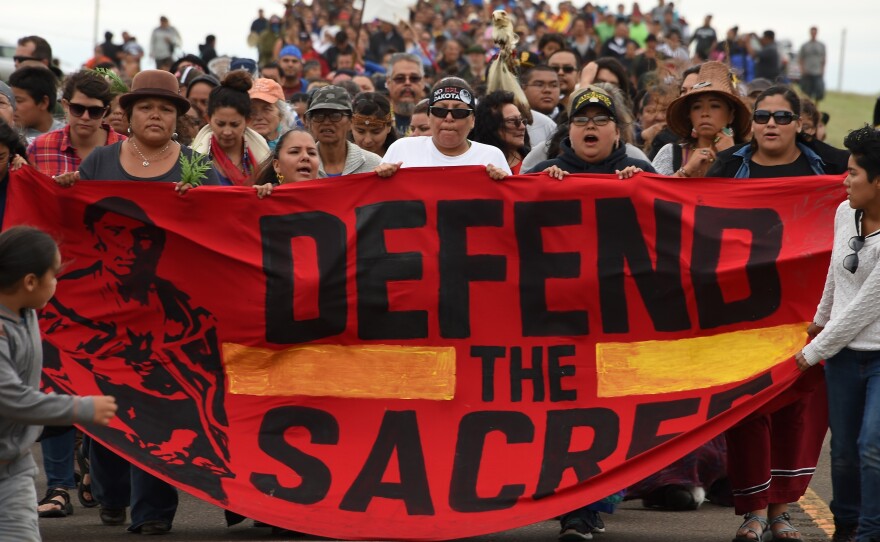

A coalition of tribes in Utah is pushing for a national monument on cultural lands there. And the most high-profile show of tribal unity since the Oregon occupation has been the protests over the Dakota Access Pipeline led by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

"The duty that tribes are claiming to their sacred sites, to ancestral homelands, places to hunt, fish and provide for themselves, those things are being ignored by the American government," said Chase Iron Eyes, a tribal attorney and member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

Iron Eyes, who is running for North Dakota's at-large seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, says with defiance that the plight of the Burns Paiute in Oregon brought a kind of awakening in Indian Country. He is optimistic that acts of civil disobedience and unarmed, peaceful protests will bring land reforms.

But for every Oregon or North Dakota example, native activists point to dozens — if not hundreds — of other cases of injustices that capture no mainstream attention.

"It may have had a momentary glimpse of a tiny second, that may have triggered a feeling of guilt and or responsibility," says Tia Oros Peters, director of the Seventh Generation Fund for Indigenous Peoples, an advocacy group. "And then it went away."

There's still deep pessimism in Indian Country. In Portland, Kennedy can't help but see how the land claims of Native Americans are treated differently from those of the militia movement.

"What if I did that with my Native brothers and sisters, and we went and occupied something, do you think we'd be let running around free, going in and out of it?" Kennedy said. "No, we'd be locked down."

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.