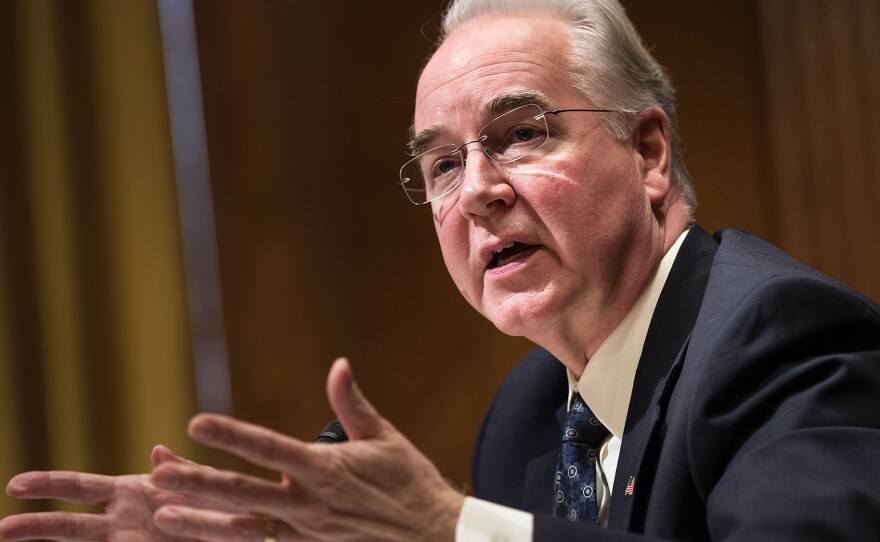

If the last few years are any guide, one group that may find itself in the crosshairs of Rep. Tom Price, President Trump's pick to lead the Department of Health and Human Services, is an influential panel of medical experts.

The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force, a group of mostly physician and academics from top universities, reviews medical practices to see whether they are supported by research and evidence.

Under the Affordable Care Act, the USPSTF's recommendations have been used to guide private insurers. If the group gives a test high marks, insurers are required to cover it. If it doesn't, they are free not to.

But letters reviewed by ProPublica show that Price twice pushed HHS to quash the task force's recommendations to limit widely used cancer screenings. The panel said that the screenings too often led to unnecessary biopsies and other harmful treatment.

Democrats on the Senate Finance Committee boycotted a Tuesday vote on Price's nomination, citing unanswered ethics questions.

In 2011, Price and other lawmakers signed a letter asking the head of HHS to "push for the withdrawal" of the panel's draft prostate screening recommendations. The panel was made up of "bureaucrats," the letter said, and decisions about prostate testing were best left to doctors and their patients. "This recommendation jeopardizes the health of countless American men," the letter said.

The task force went ahead and in 2012 recommended that men of all ages forgo using blood tests to search for prostate cancer. The recommendation didn't apply to men with a history of prostate cancer.

Three years later, Price signed two letters protesting the task force's proposed recommendations that mammograms be given every two years for healthy and risk-free women between the ages of 50 and 74, and by individual choice for women between 40 and 49. Other groups, including the American College of Radiology, recommend starting mammograms at 40 and having them every year or two.

In May 2015, Price and other lawmakers wrote that the USPSTF recommendations "would jeopardize access to screenings." In June, a second letter signed by Price and others with the GOP Doctors Caucus, went further, urging the head of HHS to ensure the recommendations weren't finalized. The recommendations, the letter said, could "result in thousands of additional breast cancer deaths."

Despite the complaints, the mammogram recommendations were issued in 2016. Proponents praised them as the fruit of the task force's independent and evidence-based approach. But the guidelines raised the ire of a much more powerful constituency: the urologists and radiologists who made billions of dollars off the testing and related procedures.

"The dirty underbelly of screening is that it's a great way to get more patients," said Dr. Gilbert Welch, professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice and a close observer of the task force's work. "The financial underpinnings are huge."

The health care industry spends more money lobbying Congress than almost any other sector, according to the tracking site OpenSecrets.org. Price, an orthopedic surgeon, took in $479,000 in health professional donations in the 2016 campaign cycle, one of the largest sums to any member of Congress.

To be sure, the industry has a host of more pressing concerns, from the ACA and Medicare and Medicaid to the cost of drugs. But the task force's recommendations have continued to draw complaints by lawmakers who received financial support from the industry.

In November, lawmakers bashed its screening recommendations during a hearing of the health subcommittee of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. The task force "can deprive patients of lifesaving services," said Rep. Michael Burgess, a Republican from Texas who received nearly $611,000 from health professionals in the 2016 campaign cycle.

His colleague, Rep. Marsha Blackburn, a Tennessee Republican who recevied $259,000 in donations from health professionals in the 2016 campaign cycle, predicted equally dire outcomes. The task force, she said, "turned its back on over 20 million women by finalizing erroneous guidelines that would limit access to mammograms."

Earlier this month, Blackburn re-introduced legislation that would, among other things, add specialists to the panel. The group currently consults with specialists in the areas they are reviewing. Critics of the proposed bill say specialists are not ideal to perform the task force's broad array of evidence reviews, and adding them could create conflicts of interest. "There is considerable support for 'draining the swamp' in Washington," Welch wrote in testimony he submitted for the hearing. "But there is no swamp currently in the task force. Please don't create one."

Questions sent to Price's office were answered by Ryan Murphy, who is currently an HHS adviser. Murphy was most recently communications director for the House Budget Committee, of which Price is chairman.

"Dr. Price's concerns — shared by others as you noted — were with specific recommendations made by the task force," Murphy said. "As a physician, Dr. Price knows firsthand the value of scientific research as well as how important it is to ensure patients and their doctors are able to make choices regarding treatments that they agree are in the best interest of the individual patient."

Price has embraced task force findings that recommend more treatment. In 2014, for example, he co-signed a letter to the HHS secretary and the Medicare administrator asking that Medicare expand its coverage for lung cancer screenings for smokers based on task force recommendations.

With the shifts in power both in Congress and under the Trump administration, proponents of the task force fear setbacks in the decades-long push for evidence-based medicine. The task force has 96 current recommendations, which it routinely updates. Its $11.6 million budget is funded through HHS's Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which has been on the lawmakers' chopping block in the past. If confirmed, Price or congressional Republicans could reduce the task force's influence or independence, or cut its funding.

"Science is really under attack," said Fran Visco, president of the National Breast Cancer Coalition. "We've spent decades building a scientific and research infrastructure and community all in order to produce the evidence that will save lives. Sometimes the science doesn't give us the answer we would like, but it actually gives us the facts and the evidence."

While some disagree with the task force's recommendations, its work is in line with a global push toward evidence-based medicine and with the guidelines of some other groups. The International Agency for Research on Cancer says there isn't enough evidence to recommend for or against mammograms for women between 40 and 49. Like the task force, the American College of Physicians says mammograms should be an individual decision for women between the ages of 40 and 49 and be provided every other year at the patient's request.

The task force and others found widespread screening often led to false positives, painful biopsies and life-altering operations for patients who were not actually at risk of cancer. Unnecessary screening also contributes to an overtreatment epidemic that the Institute of Medicine has estimated costs $210 billion a year.

Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, chairwoman of the task force, is a internist and epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco. She said the attacks by Blackburn and others risk misleading patients about the effectiveness of screening for patients who are not at risk and are free of symptoms. "Patients and clinicians need to understand the benefits and the harms so they are empowered to make the best decisions for themselves," Bibbins-Domingo said.

Regardless of what happens politically, she said, patients and doctors will still need evidence-based recommendations to make informed decisions.

The evidence-based work of the task force could be "endangered" because the panel is caught up in the political fight around the ACA, said Dr. Sheldon Greenfield executive co-director of the Health Policy Research Institute at the University of California, Irvine. "It wouldn't surprise me if it does become a casualty."

The worst outcome, he said, would be for health care in the United States to revert to the way it used to be. The old joke is that doctors ignore science and say, "I know best," Greenfield said, trumping evidence-based medicine with "eminence-based" medicine.

Marshall Allen is examining how waste and overtreatment are affecting patients and raising the cost of care. If you have evidence of wasted health care dollars, please email him at marshall.allen@propublica.org.

Copyright 2017 ProPublica. To see more, visit ProPublica.