A heart-shaped box of chocolate is a sign of love, a symbol — and often tool — of romance, and an intrinsic part of Valentine's Day.

From at least the time of the Aztecs, chocolate has been seen as an aphrodisiac. So it's reasonable to assume that it has been connected to love's dedicated day of celebration for many centuries. But, that isn't the case.

The roots of Valentine's Day are ancient but far from clear, and likely originated in the pagan Roman fertility festival of Lupercalia. Those Romans, though, exchanged not candies but whippings — part of a complicated fertility ritual that began with sacrificing a goat and dog.

This morphed into a tamer Christian feast day in A.D. 496, when Pope Gelasius I commemorated a martyred saint, Valentine. Or saints. In the third century, the Roman emperor Claudius II executed two men named Valentine on Feb. 14th, albeit in different years.

It was Canterbury Tales author Geoffrey Chaucer who first specifically linked the holiday with love birds — literally. In his 1382 dream poem The Parliament of Fowls, a large group of birds gather on "Seynt Valentynes day" to choose their mates.

Love-gazing poets followed Chaucer's lead, helping to popularize the amorous day through tales of courtly love, chivalric knights and fair maidens. Amateur bards took up their quills, too, and followed the tradition of writing verse to their paramours for the occasion — teasing couplets and sappy sonnets often surreptitiously passed in early valentines.

By the mid-19th century, Feb. 14 had become the day in Britain (and the U.S.) on which people expressed their affection by exchanging lavish cards decorated with lace, ribbons and plump, bow-and-arrow-wielding Cupids.

Amongst these maudlin missives arrived chocolate, with its lustier undertones.

From Europe's first contact with it, chocolate had a reputation for aphrodisiac powers.

Bernal Díaz Castillo, chronicler of Hernan Cortéz´s conquest of Mexico, claimed that during a banquet with Moctezuma, the great Aztec emperor was served gold cups "with a certain drink made of cacao, which they said was for success with woman." At first the Spaniard paid little attention, but then "saw that they brought more than 50 great jars of prepared cacao with its foam, and he drank that."

Mugs of the frothy drink proved immediately popular back in Spain. And chocolate was embraced with equal passion when it traveled beyond Spain's borders, going to Italy, France (perhaps in 1615, when Anne of Austria, chocolate lover and daughter of the Spanish king, married Louis XIII), and, step by step, across Europe.

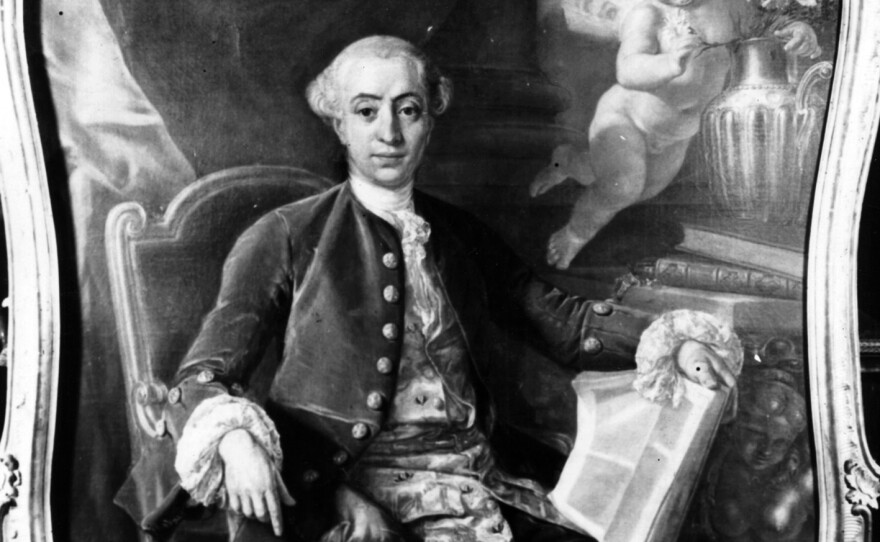

Wherever chocolate went, its reputation as a sexual stimulant seemed to follow. Giacomo Casanova called chocolate the "elixir of love" and the notorious Marquis de Sade celebrated its potency.

In Restoration England, the learned physician Henry Stubbe wrote in The Natural History of Chocolate (1662) of the "great use of Chocolate in Venery [sexual indulgence], and for supplying the Testicles with a Balsam, or a Sap."

Stubbe not only advocated the drink, but often prepared it for the insatiable Charles II, whose notorious appetite for sex was matched only by that for chocolate. In 1669, the merry monarch, England's first chocoholic, spent £229 10s. 8d. on chocolate. That's significantly more than he spent on tea (just £6), or even what his chief mistress received for an allowance (£200). For most people, though, chocolate was still an extravagance out of reach.

By the time the more staid reign of Queen Victoria began in 1837, that had changed. Valentine's Day was hitting its stride, thanks to the rise of the inexpensive penny post and mass-produced cards, and chocolate had become affordable to the middle class. Its popularity was soaring.

In 1847, the British chocolate maker J.S. Fry & Sons produced the first modern-day bar —that is, chocolate to eat rather than drink. The company combined cacao powder and sugar with cacao butter (the fat extracted from cacao beans) to form a moldable paste. A few years later, the company sold the first filled chocolates with flavored centers.

But its rival Cadbury would ultimately be the one to connect Valentine's Day with chocolate.

Tapping into the Victorian fondness for ornamentation, Richard Cadbury launched "Fancy Boxes" of chocolates in 1861. Inside, under a heavily decorated lid, assorted bonbons filled with marzipan, chocolate-flavored ganache and fruity crèmes nestled in lace doilies.

It didn't take long—1868 according to The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets — for Cadbury to create a Fancy Box in the shape of a heart for the romantic holiday. Once the chocolates had been eaten, the boxes were deeply prized by sentimental Victorians, who stored love letters, lockets of hair, and other treasured mementos inside.

The idea took wing globally and became a lasting commercial phenomenon. In the United States this year, some 40 million heart-shaped boxes of chocolates will be sold for Valentine's Day. Over half of those are from Russell Stover — many with lids festooned in enough roses, red satin and lace to please even the most lovesick Victorian.

Modern science has found little evidence of chocolate's purported libido-boosting properties. (That's not say it doesn't have highly potent psychological ones.) Regardless, for holiday celebrants, chocolate retains its allure.

According to the National Confectioners Association, U.S. consumers will shell out around $1 billion for Valentine's Day candy this year. At least 75 percent of that will be on chocolate.

And while flowers might be an even greater symbol of love, an overwhelming number of Americas prefer chocolate to a bouquet of blossoms, some 69 percent.

As Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz famously once said, "All you need is love. But a little chocolate now and then doesn't hurt."

Jeff Koehler's Darjeeling won the 2016 IACP Award for literary food writing. Where the Wild Coffee Grows will be published in autumn. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.