As the national attention to fake news and the debate over what to do about it continue, one place many are looking for solutions is in the classroom.

Since a recent Stanford study showed that students at practically all grade levels can't determine fake news from the real stuff, the push to teach media literacy has gained new momentum. The study showed that while students absorb media constantly, they often lack the critical thinking skills needed to tell fake news from the real stuff.

Teachers are taking up the challenge to change that. NPR Ed put out a social media call asking how educators are teaching fake news and media literacy, and we got a lot of responses. Here's a sampling from around the country:

Fake news "Simon Says"

In Scott Bedley's version of Simon Says, it's not those two magic words that keep you in the game, but deciding correctly whether a news story is real or not.

To start off the game, Bedley sends his fifth-graders at Plaza Vista School in Irvine, Calif., an article to read on their laptops. He gives them about three minutes to make their decision — they have to read the story carefully, examine its source and use their judgment. Those who think the article is false, stand up. The "true" believers stay in their seats.

Bedley says he's been trying to teach his students for a while to look carefully at what they're reading and where it comes from. He's got a seven-point checklist his students can follow:

1. Do you know who the source is, or was it created by a common or well-known source? Example National Geographic, Discovery, etc.2. How does it compare to what you already know?3. Does the information make sense? Do you understand the information?4. Can you verify that the information agrees with three or more other sources that are also reliable?5. Have experts in the field been connected to it or authored the information?6. How current is the information?7. Does it have a copyright?

Subtle changes

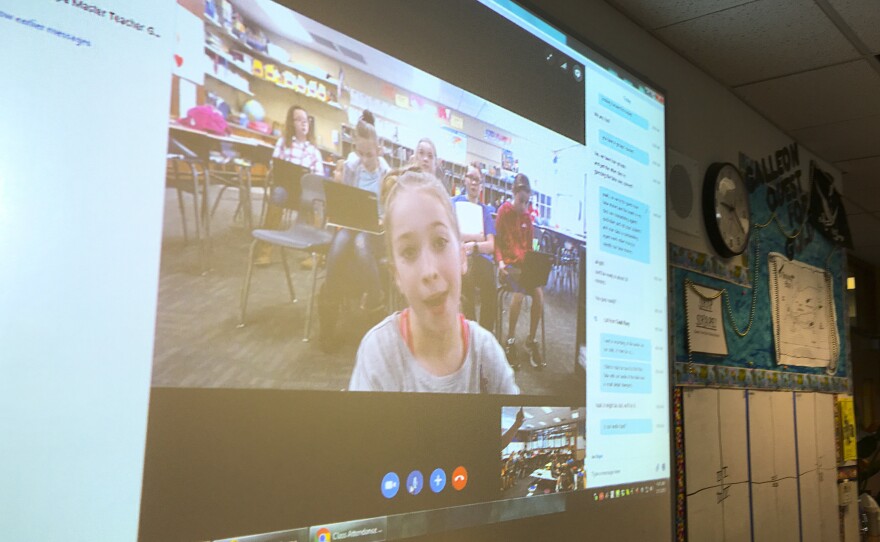

Bedley also teamed up recently with Todd Flory at Wheatland Elementary School in Wichita, Kan., to do a fake news challenge via Skype. Flory's fourth-graders chose two real articles and wrote a fake article of their own. Then, they presented them to Bedley's class in California.

The fifth-graders had four minutes to do some extra research based on the presentations, and then they decided which article out of the three were fake. Most importantly, they had to explain why they thought it was fake. Otherwise, no points.

Flory says writing the fake news article was more difficult for his students than they expected because they had to make it believable.

"It really hammered home the idea to them that fake news doesn't have to be too sensational," he says. "It can be a very subtle change, but that subtle change can have big consequences."

Every Friday, Flory's class participates in what he calls Genius Hour. His students propose a question to answer through online research. But before they took to the Internet, Flory had to walk his students through the steps: What are reliable and trusted websites? How do you effectively search on the Internet and verify information?

He uses Skype to connect his students with researchers and scientists from all over the world. He calls this "authentic research."

"It's so much more powerful for them to do some of this authentic research when they're able to hear from a scientist who's seeing firsthand the effects of climate change," Flory says. This year's class got to talk to a penguin scientist.

Flory says he's not only teaching his students effective media literacy skills; he is also helping them to be better citizens through global engagement and interaction.

Let them eat fake (news)

Remember Marie Antoinette and "Let them eat cake" — her famous line about the poor that got her in all that trouble?

Thing is, it never happened. Fake news!

For Diane Morey and her ninth-graders at Danvers High School in Danvers, Mass., that's a teachable moment.

"The media of the day didn't have Facebook, Twitter or partisan websites," Morey says. "But they did have pamphlets."

She shows her class cartoons and pamphlets from the French Revolutionary period that criticized Antoinette, and then discusses the conclusions that were made from those sources. She also includes a primary source: a letter written by Antoinette.

Morey says history is rich with examples of fake news, and since source analysis is the core of her lesson plans, she doesn't need a textbook.

"We don't study [history] to memorize Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI," she explains. "We're studying this because we can see this happening in the current-day political climate."

Morey encourages students to bring in examples of articles from today's news that don't ring true.

"Once you expose it to them," she says, "it's like a game for them, seeing, 'Hey, I'm not sure I can trust this.' "

Extra layers

For 13 years, Larry Ferlazzo has been teaching kids who are learning English how to read and write. Now, he's adding another layer: helping them figure out if what they're reading is true.

Ferlazzo teaches at Luther Burbank High School in Sacramento, Calif. He's also a blogger and journalist.

Last month, he wrote a lesson plan on addressing fake news to English language learners (ELLs), which was published in The New York Times.

He says media literacy is especially important for ELLs for two reasons. First, they're not fluent in the language they're reading, adding an extra level of difficulty in deciding what to believe. On top of that, false or exaggerated news about immigration could have a major impact on their lives.

His lesson starts off with a few examples of reliable and fake news. Then, some basic journalism stuff: Students identify the different parts of the news, from the "lede" to quotations. They enter all that into a diagram on paper so they have a visual representation of what they're reading.

That diagram eventually becomes a guide for students to write their own fake news lede that they can share with other classmates or post on a class blog.

Media consumers and contributors

In 2015, Spencer Brayton and his colleague Natasha Casey revamped a media literacy course for students at Blackburn College in Carlinville, Ill. Brayton says the key is the critical approach.

"Students come in expecting that we're going to lecture," Brayton explains. "But we have them think about certain power structures in how information is produced and how it reaches them. If they're going to understand how they're going to take it in, then they have to know how the news is going to be produced."

To take the class, students need a Twitter account. From the very first week, they are asked to follow five to 10 accounts on Twitter that promote media and information literacy, like Media Literacy Now or Renee Hobbs.

As they follow these posts and add additional ones, the goal is that they'll start to recognize fake news and other biases or viewpoints in media.

By the end of the course, Brayton says students begin to see themselves not only as creators of information, but as credible sources of information too.

The Twitter assignments encourage his students to engage with social media - retweeting, following and commenting — which Brayton says helps his students see how they play a role in spreading information to other media consumers. That means they have to take what they share more seriously.

"In looking at this issue, people seem to want a quick solution to fake news, but I'm not sure there is a solution (at least an easy one)," Brayton writes in an email. "Students need to recognize that these skills and ideas need to stay with them through adulthood, but that's easier said than done — we all fall into this trap."

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.