Ali Brivanlou slides open a glass door at the Rockefeller University in New York to show off his latest experiments probing the mysteries of the human embryo.

"As you can see, all my lab is glass — just to make sure there is nothing that happens in some dark rooms that gives people some weird ideas," says Brivanlou, perhaps only half joking.

Brivanlou knows that some of his research makes some people uncomfortable. That's one reason he's agreed to give me a look at what's going on.

His lab and one other discovered how to keep human embryos alive in lab dishes longer than ever before — at least 14 days. That's triggered an international debate about a long-standing convention (one that's legally binding in some countries, though not in the U.S.) that prohibits studying human embryos that have developed beyond the two-week stage.

And in other experiments, he's using human stem cells to create entities that resemble certain aspects of primitive embryos. Though Brivanlou doesn't think these "embryoids" would be capable of developing into fully formed embryos, their creation has stirred debate about whether embryoids should be subject to the 14-day rule.

Brivanlou says he welcomes these debates. But he hopes society can reach a consensus to permit his work to continue, so he can answer some of humanity's most fundamental questions.

"If I can provide a glimpse of, 'Where did we come from? What happened to us, for us to get here?' I think that, to me, is a strong enough rationale to continue pushing this," he says.

For decades, scientists thought the longest an embryo could survive outside the womb was only about a week. But Brivanlou's lab, and one in Britain, announced last year in the journals Nature and Nature Cell Biology that they had kept human embryos alive for two weeks for the first time.

That enabled the scientists to study living human embryos at a crucial point in their development, a time when they're usually hidden in a woman's womb.

"Women don't even know they are pregnant at that stage. So it has always been a big black box," Brivanlou says.

Gist Croft, a stem cell biologist in Brivanlou's lab, shows me some samples, starting with one that's 12 days old.

"So you can see this with the naked eye," Croft says, pointing to a dish. "In the middle of this well, if you look down, there's a little white speck — it looks like a grain of sand or a piece of dust."

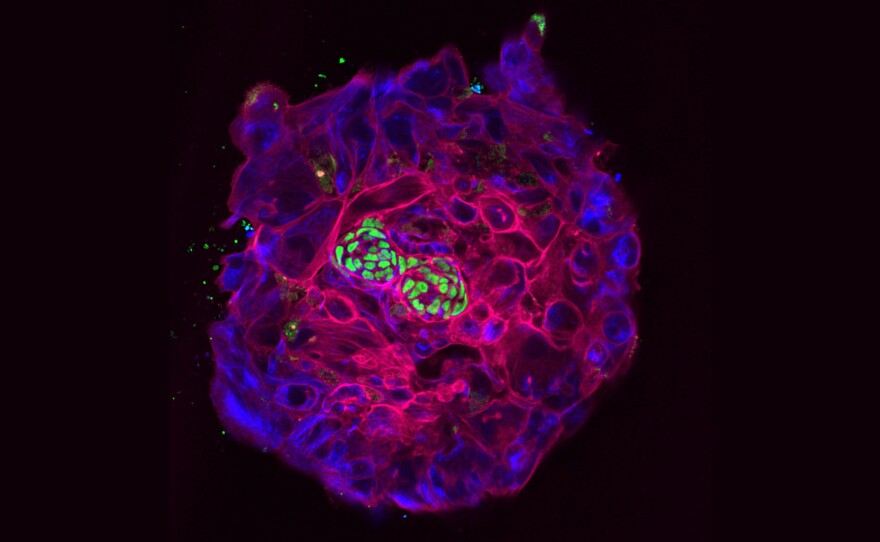

Under a microscope, the embryo looks like a fragile ball of overlapping bubbles shimmering in a silvery light — with thin hair-like structures extending from all sides.

Croft and Brivanlou explain that those willowy structures are what embryos would normally extend at this stage to search for a place to implant inside the uterus. Scientists used to think embryos could only do that if they were receiving instructions from the mother's body.

"The amazing thing is that it's doing its thing without any information from mom," Brivanlou says. "It just has all the information already in it. That was mind-blowing to me."

The embryos they managed to keep alive in in the lab dish beyond seven days of development have also started secreting hormones and organizing themselves to form the cells needed to create all the tissues and organs in the human body.

The two scientists think studying embryos at this and later stages could lead to discoveries that might point to new ways to stop miscarriages, treat infertility and prevent birth defects.

"The only way to understand what goes wrong is to understand what happens normally, or as normally as we can, so we can prevent all of this," Brivanlou says.

The 14-day cutoff

But Brivanlou isn't keeping these embryos alive longer than 14 days because of the rule.

"The decision about pulling the plug was probably the toughest decision I've made in my scientific career," he says. "It was sad for me."

The 14-day rule was developed decades ago to avoid raising too many ethical questions about experimenting on human embryos.

Two weeks is usually the moment when the central nervous system starts to appear in the embryo in a structure known as the "primitive streak."

It's also roughly the stage at which an embryo can no longer split into twins. The idea behind the rule is, that's when an embryo becomes a unique individual.

But the rule was initiated when no one thought it would ever be possible to keep embryos growing in a lab beyond two weeks. Brivanlou thinks it's time to re-think the 14-day rule.

"This is the moment," he says.

Scientists, bioethicists and others are debating the issue in the U.S., Britain and other countries. The rule is law in Britain and other countries and incorporated into widely followed guidelines in the United States.

Insoo Hyun, a bioethicist at Case Western Reserve University, advocates revisiting the rule. It would allow more research to be done on embryos that are destined to be destroyed anyway, he says — embryos donated by couples who have finished infertility treatment.

"Given that it has to be destroyed," Hyun says, "some would argue that it's best to get as much information as possible scientifically from it before you destroy it."

But others find it morally repugnant to use human embryos for research at any stage of their development — and argue that lifting the 14-day rule would make matters worse.

"Pushing it beyond 14 days only aggravates what is the primary problem, which is using human life in its earliest stages solely for experimental purposes," says Dr. Daniel Sulmasy, a Georgetown University bioethicist.

The idea of extending the 14-day rule even makes some people who support embryo research queasy, especially without first finding another clear stopping point.

Hank Greely, a Stanford University bioethicist, worries that going beyond 14 days could "really draws into question whether we're using humans or things that are well along the path to humans purely as guinea pigs and purely as experimental animals."

Embryo alternative: 'Embryoids'

So as that debate continues, Brivanlou and his colleagues are trying to develop another approach. The scientists are attempting to coax human embryonic stem cells to organize themselves into entities that resemble human embryos. They are also using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which are cells that behave like embryonic stem cells, but can be made from any cell in the body.

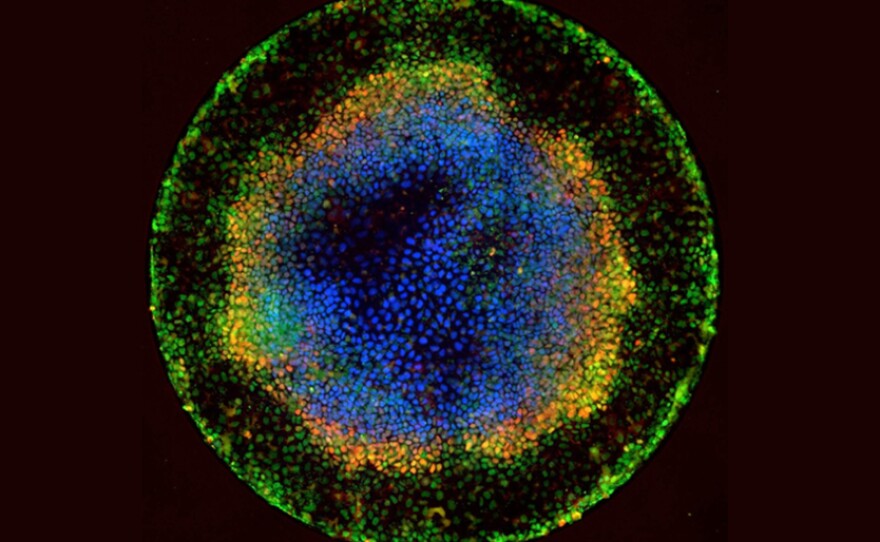

Brivanlou's lab has already shown that these "embryo-like structures" — or "embryoids" — can create the three fundamental cell types in the human body.

But the scientists have only been able to go so far using flat lab dishes. So the researchers are now trying to grow these embryonic-like structures in three dimensions by placing stem cells in a gel.

"Essentially, we're trying to, in a way, to recreate a human embryo in a dish starting from stem cells," says Mijo Simunovic, another of Brivanlou's colleagues.

In early experiments, Simonovic says, he's been able to get stem cells to "spontaneously" form a ball with a "cavity in its center." That's significant because that's what early human embryos do in the uterus.

Simunovic says it's unclear how close these structures could become to human embryos — entities that have the capability to develop into babies.

"At the moment, we don't know. That's something that's very hot for us right now to try to understand," Simunovic says.

Simunovic argues the scientists are not "ethically limited to studying these cells and studying these structures" by the 14-day rule.

There's a debate about that, however.

"At what point is your model of an embryo basically an embryo?" asks Hyun, especially when the model seems to have "almost like this inner, budding life."

"Are we creating life that, in the right circumstances, if you were to transfer this to the womb it would continue its journey?" he asks.

Dr. George Daley, the dean of the Harvard Medical School and a leading stem cell researcher, says scientists have been preparing for the day when stem-cell research might raise such questions.

"I think what prospects people are concerned about are the kinds of dystopian worlds that were written about by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World," Daley says. "Where human reproduction is done on a highly mechanized scale in a petri dish."

Daley stresses scientists are nowhere near that, and may never get there. But science moves quickly. So Daley says it's important scientists move carefully with close ethical scrutiny.

The latest guidelines issued by the International Society for Stem Cell Research call for intensive ethical review, Daley notes.

Brivanlou acknowledges that some of his experiments have produced early signs of the primitive streak. But that's a very long way from being able to develop a spinal cord, or flesh and bones, let alone a brain. He dismisses the notion that the research on embryoids would ever lead to scientists creating humans in a lab dish.

"They will not get up start walking around. I can assure you that," he says, noting that full human embryonic development is a highly complex process that requires just the right mix of the biology, physics, geometry and other factors.

Nevertheless, Brivanlou says all of his experiments go through many layers of review. And he's convinced the research should continue.

"It would be a travesty," he says, "to decide that, somehow, ignorance is bliss."

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.