In a time of high drama over executions in Arkansas, the U.S. Supreme Court hears arguments Monday in a case that could determine the fate of two of the condemned men in the Razorback state, as well as others on death row elsewhere.

At issue is whether an indigent defendant whose sanity is a significant factor in his trial, is entitled to assistance from a mental health expert witness who is independent of the prosecutors.

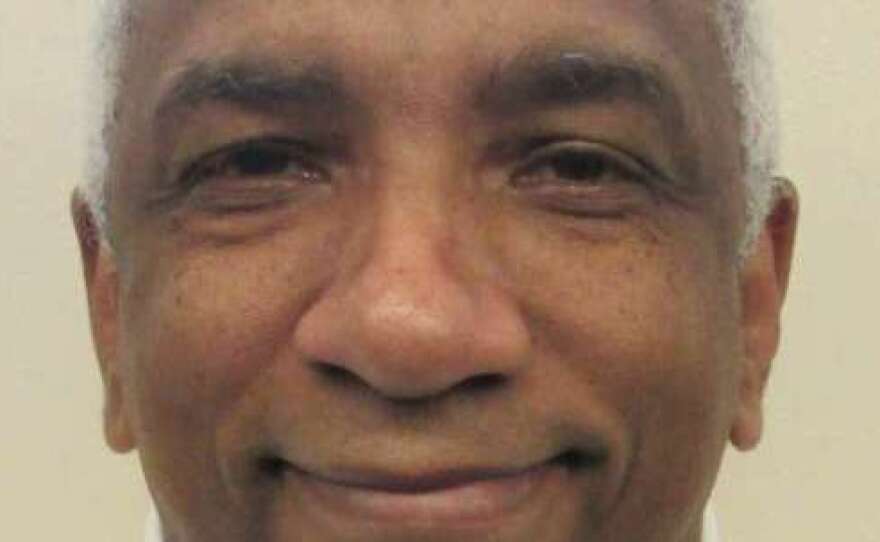

In 1986 James McWilliams was convicted of the rape and murder of a store clerk in Tuscaloosa, Ala. It is not his conviction that is before the court, but his death sentence.

A swift conviction and harsh sentence

McWilliams has been on death row for more than thirty years. His guilt regarding the 1984 rape and murder of Patricia Reynolds was not much debated – eyewitnesses saw him at the scene of the crime, and he was caught driving a stolen car with the murder weapon.

At his trial, a jury heard testimony from McWilliams' mother about his behavioral problems following a traumatic brain injury when he was a child. In rebuttal, the state put on a psychiatrist and a psychologist who testified that McWilliams suffered from no serious mental illness but tried to fake illness in mental evaluations.

And the jury, by a vote of 10-to-2 recommended he be put to death.

Under Alabama law, however, a jury recommendation is not binding on the judge. The critical sentencing hearing in McWilliams' case took place six weeks later and after the defense requested a neuropsychological evaluation of the defendant.

The report on that evaluation--produced two days before the hearing--stated that McWilliams had "organic brain dysfunction" as a result of head injuries sustained as a child.

As the hearing was about to begin, the state further produced the defendant's prison mental health records--1,200 pages long--showing, among other things, that McWilliams was being treated with psychotropic drugs.

The defense lawyer asked for a continuance; he said he needed the help of an expert witness, independent of the state, to evaluate those records and tests. The judge denied the continuance and, concluding the defendant was faking his mental illness, sentenced McWilliams to death.

Key to McWilliams' Supreme Court case is the judge's decision that because the author of the neuropsychological report was a "neutral" expert, the defense lawyer didn't need the help of another expert to explain the report or make a case of mental illness.

Final fight at the Supreme Court

The defense appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, arguing that McWilliams was entitled to that independent expert witness under a Supreme Court decision handed down a year before the McWilliams trial. In that case, the justices, by an 8-to-1 vote, ruled that when an indigent defendant can show that his sanity is a significant factor at trial, the defense is entitled, at minimum, to have "access" to an expert witness to help in the preparation of the mental health defense.

Alabama contends the expert witness does not have to be independent of the prosecution, but can be a "neutral" witness reporting to both sides.

Stephen Bright, who is representing McWilliams at Monday's oral arguments, says "so much of what happens in the criminal courts depends on experts." Mental health is one of those areas where it comes up most often, he says. And, as exemplified by this very case, there are often discrepancies between experts' findings.

The vast majority of death penalty states already provide such independent expert witness help for an indigent defendant.

Two Arkansas death row inmates, Don Davis and Bruce Ward, were scheduled to be executed on Monday, April 17, and the U.S. Supreme Court and Arkansas Supreme Court blocked the executions until McWilliams' case is decided.

The Arkansas governor scheduled the executions for eight death row inmates between April 17 and 27, and so far one inmate has been executed. Two are scheduled to die Monday night.

On Monday the U.S. Supreme Court will also hear another death penalty case coming out of Texas, involving a technical procedural issue of when, where and how the defendant could claim ineffective assistance of counsel.

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.