The U.S. foster care system is overwhelmed, in part because America's opioid crisis is overwhelming. Thousands of children have had to be taken out of the care of parents or a parent who is addicted.

Indiana is among the states that have seen the largest one-year increase in the number of children who need foster care. Judge Marilyn Moores, who heads the juvenile court in Marion County, which includes Indianapolis, says the health crisis is straining resources in Indiana.

"We've gone from having 2,500 children in care, three years ago, to having 5,500 kids in care. It has just exploded our systems," Moores says.

While laws in all U.S. states require that child welfare agencies make "reasonable efforts" to reunify parents with their children, Moores says that process can be especially traumatic for children whose parents often relapse.

She says that more legal consideration should be paid to the child's rights and safety and that "right now, that balance does not tip legally in favor of the child."

Earlier this year, President Trump declared the opioid epidemic a public health emergency. But that designation "didn't come with money," Moores says. "And that is sadly what the necessity is." She says reform is needed, and it should focus on "how much in the way of resources should be devoted to trying to reunify children with parents who cannot conquer their addiction."

Interview Highlights

On what kind of cases she is seeing

One of the hallmarks is we're seeing many younger children than we had seen before. I think the average age is about three years younger than we had seen. We see lots and lots of opioid-addicted babies following their releases from NICUs [neonatal intensive care units] where they went through withdrawal from opioid addiction that they suffered in utero. We see kids — little, itty-bitty kids — that are found in car seats in the backs of cars where parents have overdosed in the front seat. And because of the age of the children, we can't safely leave them with addicted parents. And so, it has just over-rolled our system.

On how her division has been grappling with the influx

Well, we're scrambling. I've had kids that I've had to find a foster home for — not in Marion Country, but in Lake County, which is by Chicago. That's a two-and-a-half-hour drive. How can I reunify parents with a child where they can't even see their child on a regular basis?

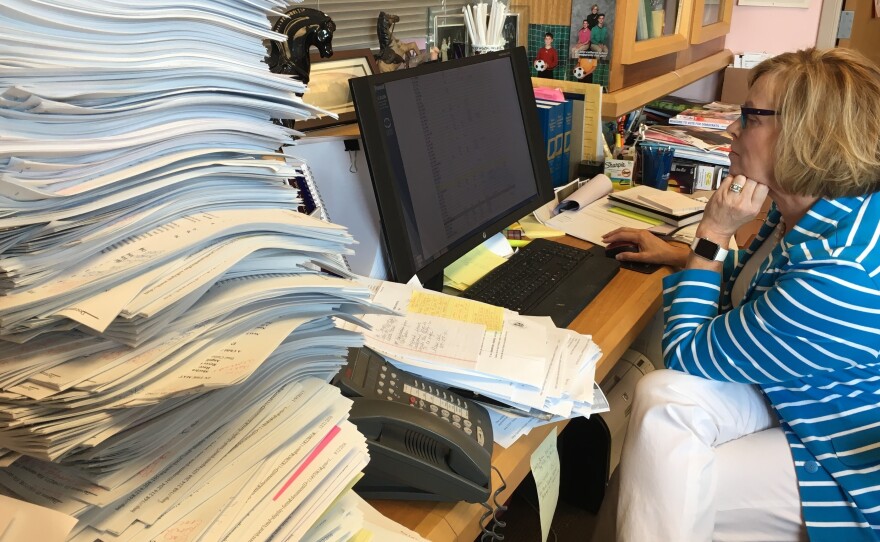

We have kids who are sleeping in the Department of Child Services office because there are no homes for them that can be quickly found. Our public defenders, our DCS case managers, our guardians ad litem, our judicial officers are all overwhelmed. But everyone pulls together to try their very best to ensure child safety.

On whether to prioritize the reunification of child with a parent who is an addict

There's a lot of debate about that, but the law requires that reasonable effort be made to reunify first. Sadly, in some cases, the law has determined that parents have a due process right to their children. In other words, we treat children like chattel of their parents, like possessions, and these are Supreme Court precedent. I think that many of those precedents were issued at a time when keeping kids with parents, there were extended families who were able to help support and take care of kids, but we don't have that now. And I wonder if the law isn't antiquated in that regard.

It's been incredibly difficult for funding to keep pace with the need and the demand for services. Our director of Department of Child Services just resigned and issued a letter saying that the constraints that the budget was placing on her all but ensured children would die.

On whether President Trump's designation has had any effect

It didn't come with money. And that is sadly what the necessity is. That and, we need legal reform. We need reform that literally looks and says, "How much in the way of resources should be devoted to trying to reunify children with parents who cannot conquer their addiction?"

The recidivist rate for opioid addiction is somewhere in the 70 percent. We can't keep parents sober long enough to reunify their children with them. And even those efforts come at great costs to the taxpayers, and they come at even greater costs for the children because being in this system is a trauma for children and these back-and-forth attempts in trying to reunify them with their parents is scarring these children.

On addicts whose only motivation to get clean is becoming a good parent

I think that we need to make reasonable efforts to try and reunify, but we have to have a better balancing of the child's right to safety, security, a right to pursue happiness, and honor that child's life as much as we're honoring the parents' right. And right now, that balance does not tip legally in favor of the child.

Tim Peterson, Martha Wexler and Sarah Handel produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Emma Bowman adapted it for the Web.

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.