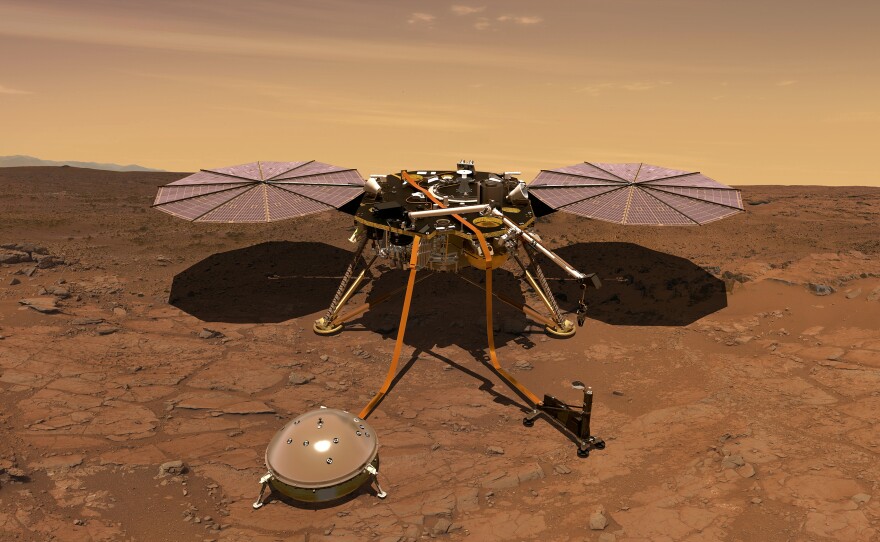

NASA is heading back to Mars. If all goes well, a two-stage Atlas V 401 will lift off from California's Vandenberg Air Force Base on Saturday morning. Onboard will be a lander named InSight, an $813.8 million mission to study the interior of the Red Planet.

Recent Mars missions have snapped pictures of the surface, studied rocks, dug in the dirt and looked for signs that water once flowed on Mars. But as Insight's principal investigator William "Bruce" Banerdt sees it, that's just scratching the surface.

"Ninety-nine-point-nine percent of this planet has never been observed before," Banerdt says. "And we're going to go and observe it with our seismometer and with our heat flow probe for the very first time."

The heat flow probe is basically a 16-foot long thermometer that Insight will pound into the planet to take its temperature.

InSight's seismometer will measure earthquakes — or more properly, "Marsquakes." Quakes on Mars don't happen as frequently as they do on Earth, but they do occur and have been detected by previous Mars landers.

Banerdt says the shape and strength of the waves those quakes generate can tell scientists a lot about the planet's inner makeup: "The thickness of the crust, the size of the core and the density of the various divisions, core mantle and crust."

To make those calculations, Banerdt says they need to know the location of a quake on Mars. To find the location of a quake on Earth, geologists would use multiple seismometers to triangulate the epicenter. InSight has only one seismometer, but Banerdt says it's still possible to find a location, which can be done by measuring the time delay when different quake waves arrive at the seismometer.

"It's not [a technique] used on the Earth because it's a lot easier to combine all the seismometers that we have," Banerdt says. "That data is easily available on the Internet. But on Mars we have to be just a little bit more clever."

InSight is not a rover. Once it lands in Elysium Planitia, a flat plain near the Martian equator, it will stay put.

The mission's deputy principle investigator, Suzanne Smrekar, says one of InSight's experiments will measure how much Mars wobbles as it rotates on its axis. If Mars were a solid sphere, it would rotate smoothly. But if it wobbles — as scientists suspect it does — that would indicate something non-solid is moving around in the interior.

As scientists get ready to probe past Mars' surface, it's worth noting that scientists haven't known much about Earth's interior for all that long.

"A hundred years ago, we didn't know what the layers were inside the Earth, we didn't know anything about plate tectonics," Smrekar says.

There's lot of geologic activity on Earth today, and she says that used to be the case on Mars. But things on Mars have slowed to a geologic crawl, and understanding the planet's interior could provide clues as to why that is.

"This will give us the ability to go back in time, into that early period when Mars was very active, and really understand how the planet started forming its layers," Smrekar says.

To really understand any planet, "we have to understand how its interior is connected to its surface connected to its atmosphere," Smrekar says. "With our mission we'll be able to finally get a look inside Mars."

And Banerdt says Insight is bound to provide some surprises.

"One always expects something completely out of the ordinary when you're completely in the dark to begin with," he says.

Insight is scheduled to take off at 4:05 a.m. PT on Saturday. If the weather is clear, NASA estimates people as far north as Bakersfield, Calif., and as far south as Rosarita, Mexico, should be able to see InSight set off on its 300 million-mile journey to Mars.

The lander is set to arrive on Nov. 26.

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.