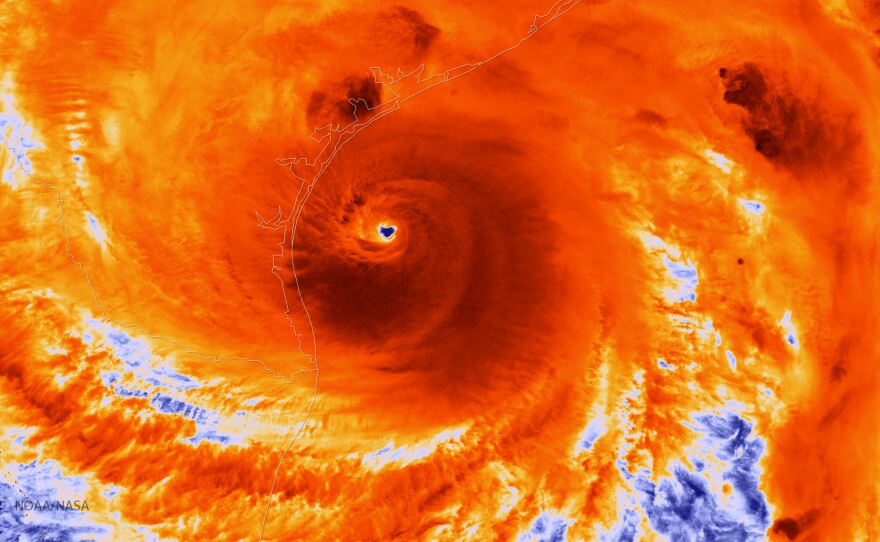

Hurricane Harvey, which devastated South Texas last August, was powered by what scientists say were the highest ocean temperatures they've ever seen in the Gulf of Mexico.

Portions of the Gulf to the south of the Texas coast were 86 degrees Fahrenheit. That's several degrees higher than normal — and it's heat that drives big storms.

Kevin Trenberth, an atmospheric scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, says the extraordinarily high heat lasted for several days before the storm. "Record high ocean heat values not only increased the fuel available to sustain and intensify Harvey," he says, "but also increased its flooding rains on land."

Warm sea surface temperatures create more water vapor, which rises into the atmosphere, then falls as rain during a tropical storm. Trenberth, writing in the journal Earth's Future, says measurements showing the amount of evaporation as the storm formed match the amount of rain that fell during the storm.

Another feature of this massive storm was the fact that Harvey didn't leave significantly cooler water in its wake. Normally, hurricanes suck heat out of the water and also create ocean mixing, which brings cooler water to the surface. But measurements showed that the Gulf barely cooled at all, suggesting little mixing.

Cyclical changes in weather, such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation that occurs every few years, affect ocean temperatures. And this is not the first time Gulf waters have been exceptionally warm.

But Trenberth says that "Harvey could not have produced so much rain without human-induced climate change," which has been warming oceans for years. He adds that a warming planet will set the stage for more-intense and wetter storms.

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.