Updated at 6:15 p.m. ET

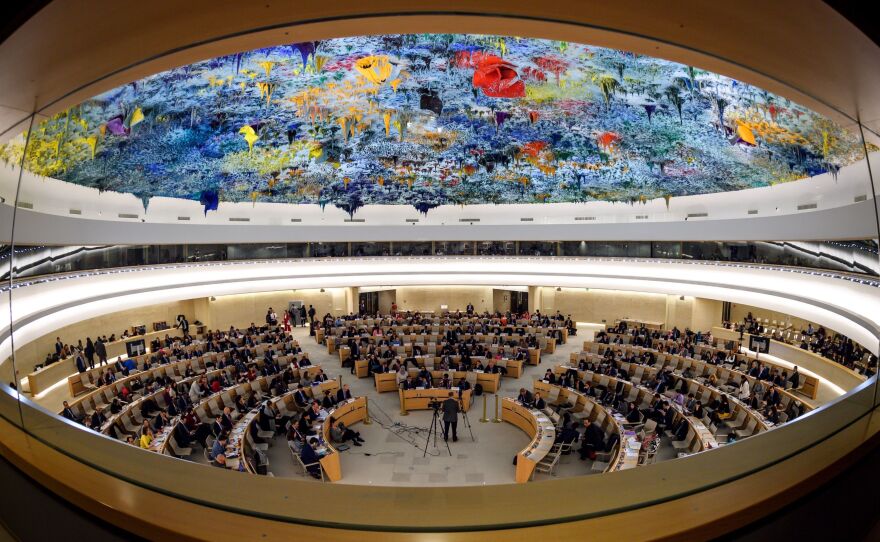

After more than a year of complaints and warnings — some subtle and others a little less so — the Trump administration has announced that the United States is withdrawing from the United Nations Human Rights Council. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Ambassador to the U.N. Nikki Haley announced the decision in a joint statement Tuesday.

"I want to make it crystal clear that this step is not a retreat from human rights commitments," Haley told the media. "On the contrary, we take this step because our commitment does not allow us to remain a part of a hypocritical and self-serving organization that makes a mockery of human rights."

The move comes as little surprise from an administration that frequently has lambasted the 47-member body for a gamut of perceived failures — particularly the dubious rights records of many of its member countries, as well as what Haley has repeatedly called the council's "chronic bias against Israel."

Haley harked back to a speech she delivered to the council one year ago this month, in which she laid down something of an ultimatum. At that point, she told members that they must stop singling out Israel for condemnation and must clean up their roster — which includes Venezuela, China and Saudi Arabia, among others — or the council could bid the U.S. farewell.

In remarks to the Graduate Institute of Geneva, given the same day as her council speech, Haley made the matter plain.

"If the Human Rights Council is going to be an organization we entrust to protect and promote human rights, it must change," she said. "If it fails to change, then we must pursue the advancement of human rights outside of the council."

In the year that has elapsed since those speeches, such reforms never happened. Instead, she said, the council stayed silent on violent repression in Venezuela, a member state, and welcomed another country with a problematic record of its own, the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

"The council ceases to be worthy of its name," Haley said, explaining the U.S. withdrawal. "Such a council in fact damages the cause of human rights."

Trump's diplomatic team is not the first within the U.S. to voice such criticism.

When the council was first established in 2006, the administration of George W. Bush withheld its membership over similar concerns. And when the Obama administration announced in 2009 that it would reverse course and seek membership, the U.S. ambassador to the U.N. at the time, Susan Rice, said the decision was made out of a belief "that working from within, we can make the council a more effective forum to promote and protect human rights."

Several U.S. critics, in condemning the decision Tuesday, echoed precisely this desire for reform as a principal reason to stay in the council, not leave it.

"The UN Human Rights Council has always been a problem. Instead of focusing on real human-rights issues, the council has used its time and resources to bully Israel and question Israel's legitimacy as a sovereign state," Rep. Eliot Engel, the ranking Democratic member of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, said in a statement Tuesday. "But the way to deal with this challenge is to remain engaged and work with partners to push for change.

"By withdrawing from the council, we lose our leverage and allow the council's bad actors to follow their worst impulses unchecked — including running roughshod over Israel."

Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, said the U.S. focus on Israel's treatment has actually caused American officials to lose sight of the good work the council has done elsewhere.

"The U.N. Human Rights Council has played an important role in such countries as North Korea, Syria, Myanmar and South Sudan, but all Trump seems to care about is defending Israel," Roth said in a statement to NPR. "Like last time when the U.S. government stepped away from the Council for similar reasons, other governments will have to redouble their efforts to ensure the Council addresses the world's most serious human rights problems."

And Richard Gowan, a fellow at New York University's Center on International Cooperation, told NPR's Michele Kelemen that there is another potential issue muddying the waters of this decision: the recent condemnations leveled at the Trump administration's immigration policies by international human-rights officials.

In a span of less than two months, U.S. officials have separated some 2,300 children from their parents after they crossed the border into the U.S., according to the Department of Homeland Security. And the administration's policy has attracted a sharp rebuke from the U.N. high commissioner on human rights, Zeid Raad al-Hussein.

"The thought that any State would seek to deter parents by inflicting such abuse on children is unconscionable," he said Monday, in comments opening the 38th session of the Human Rights Council.

Hussein pointed to criticism from the president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, who referred to the border policy as "government-sanctioned child abuse." And the commissioner noted that the U.S. remains the sole U.N. member not to ratify the Convention of the Rights of the Child, a landmark agreement passed nearly three decades ago.

"I don't think [Tuesday's withdrawal] is linked to Prince Zeid's criticism of U.S. immigration policies," Gowan acknowledged, explaining that the high commissioner is technically separate from the council. But, Gowan added, "The timing looks just awful for Nikki Haley and Secretary Pompeo."

Pompeo, however, said the matter is simple: The U.N. Human Rights Council is not capable of fulfilling its mission without reform — and those desired reforms remain unfulfilled.

"The Human Rights Council has become an exercise in shameless hypocrisy, with many of the world's worst human-rights abuses going ignored and some of the world's most serious offenders sitting on the council itself," he said Tuesday. "The only thing worse than a council that does almost nothing to protect human rights is a council that covers for human-rights abuses — and is therefore an obstacle to progress and an impediment to change."

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.