Not since a deadly famine was ravaging North Korea in 1997 has the country seen its economy contract at such a large rate as it did last year. After a couple of years of growth, the country's estimated gross domestic product went reeling in the other direction in 2017, shrinking 3.5 percent, according to South Korea's central bank.

The Bank of Korea detailed the stark figures in a report released Friday. In the absence of reliable public information from Pyongyang, the Seoul-based bank is widely considered the region's most knowledgeable source on the economic status of its northern neighbor — and bank leaders say the North's nuclear ambitions and the international penalties that have resulted have done a number on that economic well-being.

"The negative growth is attributable to a drop in its mining output and a retreat in its heavy and chemical industries, as the United Nations imposed tougher sanctions over its nuclear and missile activities," one official told South Korea's Yonhap news agency.

Those declines appear steep in Friday's report.

Mining production in North Korea, which relies on coal as its No. 1 export, dropped 11 percent in 2017 — a breakneck reversal from the 8.4 percent growth it had seen the year before. Production in heavy and chemical industry also dropped more than 10 percent.

The sectors of the North Korean economy have been targets of U.N. sanctions in recent years. Penalties assessed in November 2016, aimed at punishing Pyongyang for a nuclear test two months earlier, sought specifically to block its coal exports beginning in 2017. Months later, China, the North's most important trading partner, announced it would suspend imports of North Korean coal.

The moves have taken a toll on the country's international trade, as well.

Its exports, in dollar amount, showed a decrease of more than 37 percent compared with 2016. Again, coal can be considered a principal cause of the broader plummet: Exports of mineral products declined more than 55 percent, according to the Bank of Korea, while textile and animal products declined roughly 22 percent and 16 percent, respectively.

All told, these GDP woes are unlike anything seen in North Korea since the mid-1990s, at least on paper. In 1997, the last time the country felt an economic contraction sharper than last year's, North Koreans were clawing their way out of a years-long famine that's believed to have killed at least 2 million people. At that time, the bank says North's GDP had contracted 6.5 percent.

Though the report's numbers only address the 12 months leading up through last December, it's unlikely the new year brought good news for North Korea's economic outlook. Quite the opposite, in fact.

"The sanctions were stronger in 2017 than they were in 2016," noted Shin Seung-cheol, head of the the bank's national accounts coordination team, according to Reuters.

Those sanctions, which came amid a flurry of a missile tests and escalating rhetoric, included China's decision to completely ban imports of North Korean coal, iron and sea food as part of a volley of U.N. sanctions.

Despite occasional violations, U.S. Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats said Thursday he believes "those sanctions are basically being held."

"We continue to have Chinese support; we continue to have Russian support," he explained during a security forum Thursday. "So, right now we have the pressure on them to go forward and we'll see how it plays out."

North Korea has paused its weapons tests in recent months, adopting an apparently gentler stance toward the international community and seeking conversations about the prospect of denuclearizing in return for sanctions relief. The thaw in relations reached a milestone last month, with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un and President Trump meeting personally in Singapore to discuss the prospect.

Since then, however, doubts have been mounting about how much progress both sides have really made toward reconciliation.

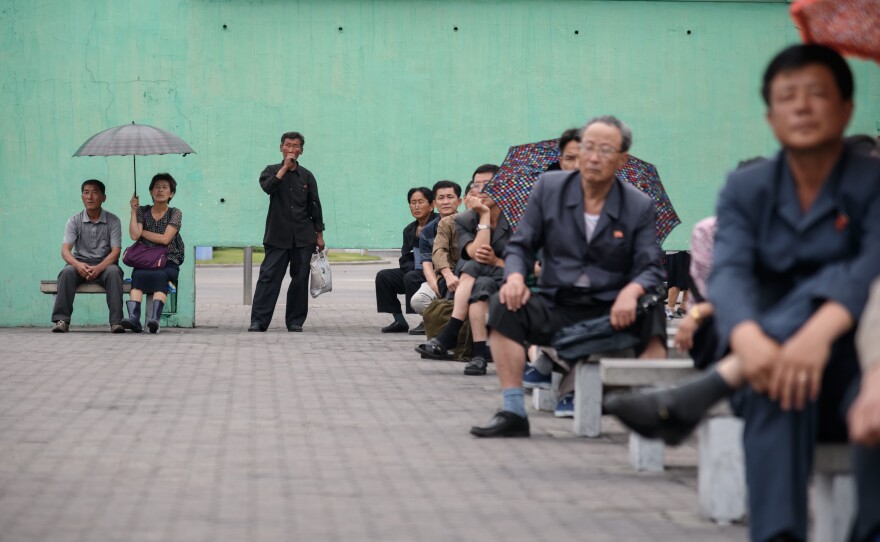

In the meantime, it remains unclear what these high-level moves toward rapprochement may spell for the situation on the ground in North Korea — where the U.N. estimates roughly 40 percent of the population is undernourished.

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.