A few years ago, historian Douglas Selvage discovered the blueprint for a fake news campaign. It was a 1985 cable from the Stasi, the former East German police, outlining how the Soviet Union and its allies were working to promote the idea that AIDS was an American biological weapon. "We are carrying a complex of active measures, in connection with the appearance in recent years, of a new, dangerous disease in the United States: Acquired Immuno Deficiency Syndrome, or AIDS."

It was a smoking gun, proving what intelligence agencies on both sides of the Cold War already knew — that the Soviets had played a key role in spreading false rumors about the AIDS epidemic.

Fake news isn't a 21st century creation of the digital age. It has a long track record. Selvage says the Soviets used dezinformatsiya during the Cold War to harden people's existing beliefs and fears, to sow divisions among Americans. It's eerily similar to the 2016 campaign season when Russian entities are said to have inserted fake stories and profiles on Facebook. In recent months, Silicon Valley has stepped up its fight against disinformation. Tuesday, Twitter and Facebook said they had taken down hundreds of fake accounts linked to Iran. Facebook also purged some accounts originating in Russia. And just a few weeks ago, Facebook deleted 32 pages and profiles it deemed false.

Back in the 1980s, the rumor that AIDS was human-made was based partially on a report written in 1986 by Russian-born biophysicist Jakob Segal. "It was very successful," explains Selvage. "The local press picked up on it. And then also British newspapers picked up on it. It started to spread around the world." Even U.S. newspapers picked up the story. Papers read specifically by African-American and gay communities, both of which were being devastated by the epidemic. "AIDS/Gay Genocide" read a headline in the Gay Community News, based in Boston, which quotes Segal extensively.

"Link AIDS To CIA Warfare" read another article, from the New York Amsterdam News, a paper read by African-Americans. The article begins by introducing a "prominent physician" who "has charged that the spread of AIDS epidemic in some part of Africa is due largely to bacteriological and chemical experiments conducted over the years in these areas by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency."

"A cycle of misinformation" is how Selvage describes it. Conspiracy theorists in America would cite KGB sources, and vice versa.

But it's not entirely fair to dismiss those beliefs as conspiracy theories. The history of racial discrimination and medical malpractice toward American minorities made these rumors spread like wildfire.

"There's a history, a legacy of mistrust, that makes explanations like these all the more credible, all the more likely, and all the more believable," says Robert Fullilove, a professor of sociomedical sciences at Columbia University.

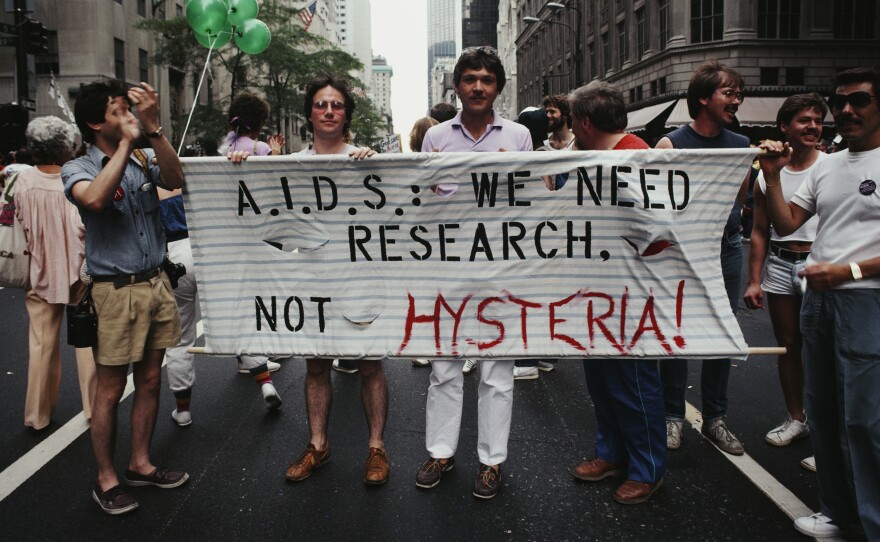

He describes the onset of the epidemic as a time of confusion and fear among the general population and even medical professionals. "People were trying their best to make sense of a condition that came out of nowhere and seemed to attack marginalized people. Gay men. Blacks and Latino men and women."

When AIDS showed up in the early '80s, it was less than 10 years after the infamous Tuskegee experiments, in which black men with syphilis went untreated so scientists could study how the disease ravaged their bodies. Why not assume this was yet another blow to the community?

Fullilove points to something else at play in the spread of rumors: the Reagan administration's lack of response to the epidemic. President Ronald Reagan did not address the situation until several years after it had begun.

Russia finally acknowledged, in 1992, a KGB disinformation campaign about AIDS. But Fullilove says he still hears the rumors: " 'So, Doc. Where do you think this came from?' If I heard that once, I must've heard it a thousand times. And that's not an exaggeration."

The tactic of weaponizing existing American racial tensions seems to work. And maybe that's because there's just a lot to work with. During a recent Facebook purge, one of the most popular pages to get suspended was called "Black Elevation." It protested racial injustice and police brutality. That's the thing: The page might have been fake. But many of the incidents it spoke of were very real. And so were the feelings about them.

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.