In the fictional world of Marvel's Black Panther, the Afro-futurist utopia of Wakanda has a secret, almost magical resource: a metal called vibranium. Its mythic ability to store energy elevated vibranium to a central role in the fictional nation's culture and the metal became part of Wakandan technology, fashion and ceremony.

Of course vibranium isn't real. But one metal has held a similarly mythic role for over 2,000 years in many cultures across the African continent: iron.

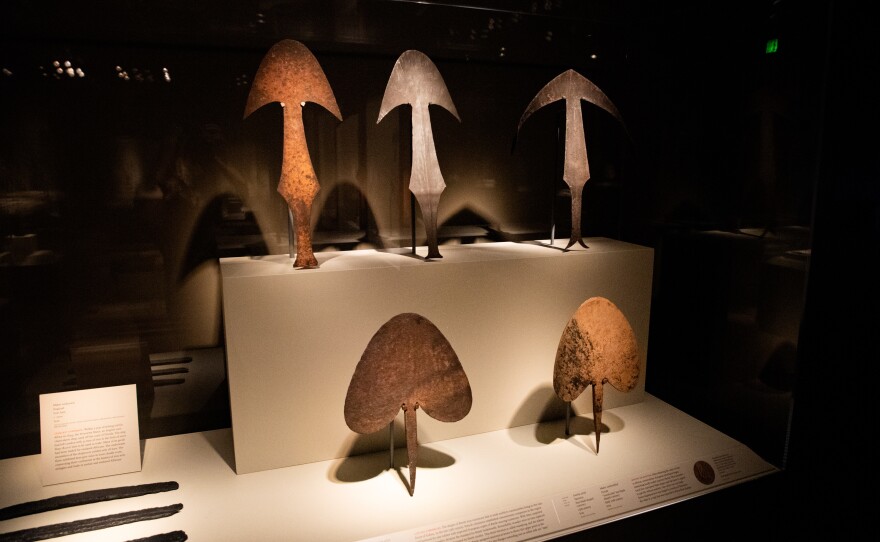

African blacksmiths have been crafting agricultural tools, musical instruments, weapons and symbols of power and prestige out of the raw material for ages. "Striking Iron: The Art of African Blacksmiths," a new exhibit at the National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C. showcases Africa's rich history of ironworking through 225 tools, weapons and adornments from over 100 ethnic groups across Africa.

The show illustrates the "individual virtuosity, diversity and complexity" of African blacksmiths, says Augustus Casely-Hayford, the museum's director. "Artists and makers learning from others, passing on skills and techniques."

"It's a glorious way to tell the story of the African continent," he adds.

The exhibition, which runs until October 20, features many works from the 19th and 20th century but contains some artifacts from the early days of African ironworking.

Africans began extracting iron ore from the continent's rich deposits roughly 2,500 years ago. Evidence from archaeological sites in what is now modern-day Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo and Zimbabwe show that blacksmithing was a widespread practice across sub-Saharan Africa.

To transform iron into something a blacksmith can work with, it must be refined, or smelted, by applying intense heat to remove impurities from the ore.

Across Africa, workers practiced "bloomery smelting": heating iron-containing minerals in a furnace until the iron particles separate — or "bloom" — from the rest of the minerals, leaving pure, malleable iron.

"Africans were practicing this method at the same time as Europeans," says Dewey, referring to the early centuries of the Common Era.

According to Tom Joyce, the lead curator of the exhibit who is himself a blacksmith, Africans actually preceded Europeans by 300 to 400 years in the development of bellowing technology that allowed more efficient smelting by preheating the iron with a mixture of hot and cool air.

African ironworks were of such high quality that traders from Europe and elsewhere sought them as exports as early as the 11th century, according to William Dewey, a co-curator and art historian at Penn State University.

But what truly sets African ironworks apart from other parts of the world are the forms that blacksmiths fashioned from these blooms.

Expertly crafted iron plows, sickles and hoes were essential for the development of agriculture across Africa. Blacksmiths tailored the design of these tools to meet the continent's varied climate, terrain, soil types and crops, yielding a wide diversity of forms. Such craftsmanship elevated blacksmiths to prominent roles in many African societies, according to Marla Berns, a co-curator of this exhibit. She is also the director of the Fowler Museum at UCLA, which debuted "Striking Iron" last year.

A blacksmith's artistry could also transform the tool into a ritual object, symbolizing productivity and fecundity, says Berns.

Some works were crafted with no practical purpose but solely for ritual use. Rain wands from Nigeria evokes the form of lightning or slithering snakes, both presages of rain to come, says Berns. She says "they were planted in the earth and were intended to draw the life force of the Earth up toward the heavens in order to bring down the rain."

African blacksmiths also built musical instruments that echoed the rhythmic soundscape of the forge. Large clapperless bells and smaller thumb pianos took a variety of forms, enabling an even wider variety of music.

According to Berns, these instruments weren't so much used for entertainment but for spiritual purposes. "They're potent, powerful objects, used to create sounds to call the spirits, the ancestors or to call people to action across large distances," she says.

Blacksmiths everywhere also make tools of violence. Across central and equatorial Africa, smiths forged throwing knives with the perfect proportions to be "hurled or swung with devastating accuracy," according to exhibit materials.

Many blacksmiths added bold flourishes to the weapons — distinctive curves or intricate engravings — to convey authority and prestige to their owner. Dewey says kings would often bear such symbolic weapons, sometimes purportedly forged by the king himself.

In many parts of Africa, ironworks of such clear craftsmanship were treated as currency. Expertly crafted blades or tools, too ornate and large for practical use, would serve as payment for a dowry or large purchases like horses, according to Joyce.

For example, the Nkuthshu and Ndengese peoples in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo until the mid-20th century traded oshele, large ornate currency tokens reminiscent of throwing knives.

As European powers expanded their exploitation on the African continent during the 15th century, they tried to undermine African iron production, making the locals reliant on the colonial economy. Local smelting was sometimes prohibited, and blacksmiths were often specifically targeted by slavers for their skills to transport them to other colonies, like the Americas.

European blacksmiths also mass-produced replicas of iron currency tokens during the colonial era to destabilize local markets. Kwele blacksmiths in present-day Gabon countered these forgeries by creating unique twists in their works that were harder to replicate.

Taken together, the exhibit highlights the diversity, ingenuity and sheer beauty of African blacksmithing, says Christine Mullen Kreamer, deputy director and chief curator of the National Museum of African Art. "I hope the exhibit challenges perceptions of Africa and African artists."

Jonathan Lambert is a freelance science writer based in Washington, D.C. Follow him on Twitter @evolambert

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))