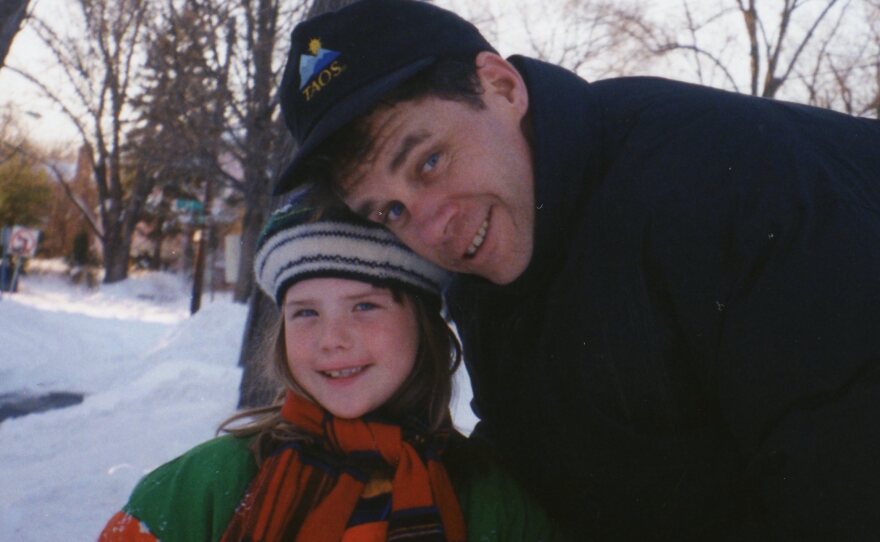

When New York Times media columnist David Carr died suddenly of previously undiagnosed lung cancer in 2015, he left behind a legacy as a journalist, a mentor and a father.

"He was so good at inspiring confidence in you," daughter Erin Lee Carr says. "He had an ability to spot talent in a way that I've seen sort of unrivaled — whether it be Ta-Nehisi Coates or Lena Dunham or his colleague A.O. Scott at the Times."

But David Carr's role as a mentor to his daughter was complicated by his addiction to alcohol and crack cocaine. His 2008 memoir, The Night of the Gun, describes how, earlier in his life, he put Erin and her twin sister Meagan into foster care before eventually getting sober.

In the memoir All That You Leave Behind, Erin, now a documentary filmmaker, writes about how her father's past affected her life, and how she dealt with her own addiction to alcohol. She sees her book as a continuation of her father's spirit.

"He talked about life being a grand caper and that we hope it doesn't end soon ... " she says. "The book is about extending the caper."

Interview Highlights

On how writing the book was more painful than cathartic

Making films is a collaborative experience and that's what I do for a living. And writing is this intensely solo activity. And so I was with him in a way. I was next to him, next to his words, I listened to almost every interview he ever did. I really wanted to educate myself in all things David Carr, not just the father which I experienced. But I found it to be so painful to, like, to get access to him in his words in these emails and yet not have him anymore.

On telling people about her father's history of addiction

I don't think he thought that I was going to tell anybody about it. He never said, "This is something to be ashamed of." But he sat my twin and [me] down and said, "This is your story, but you have to be really careful about who you tell it to." And he talked about that you can't trade it for intimacy or things like that. I was a little kid. But what I understood from the conversation was that I had a very different origin story than that of other kids I knew growing up, and how that made me different I wasn't sure. I just knew that he was sober now and he was able to take care of us.

On learning about her father's past, including the time when he left her and her twin sister alone in a car while he bought drugs

When I was in high school I knew that my dad was writing a book and I knew it was going to be about his former life as someone who was addicted to crack. He came upstairs and he had this big pile of pages and he was kind of handing it to me as if it were like a hot potato, like it was radioactive. He said, "This is the book. I need you to look at it. You have two weeks. If there's anything in there that makes you horribly uncomfortable, I will take it out. But I'm going to tell you, it's rough."

Maybe he had told me [that] story before, but to see it written in the book in that way was a completely different experience. I sort of choked on the emotion — like, I thought how close I came to not being there anymore. It really made me think about his story differently. It wouldn't be the last time he would put my life at risk because of drugs and alcohol. We said something in my family: That drugs explain everything, and excuse nothing. So we had to reconcile that he was still the person that left us alone.

On her own alcohol addiction, and her father encouraging her to get sober

I felt really unlovable. Being a part of the origin story of being these miracle babies that were able to grow up and be healthy and live their own lives, I thought it was not going to go well, like there was going to be a turn in the story. ... It wasn't until I was fired in 2013 when he sat me down and said, "You have two options in front of you: One is the path of alcoholism and insignificance, and two is you stop drinking and you see who you can become."

On relapsing after her father's death

The six months after he died I would have this push-pull of: Should I drink? should I not? ... On the six month anniversary of his death, it was one of those nights where I could not hold it back and I drank so much the next day I felt like killing myself. And I just had a moment of reckoning, saying, "This is not the life that my father would want me to live. And he's not here anymore, and I have to try to make him proud. And so why don't I just try to do a day without alcohol again? OK. I'm going to try a week without it. Now I'm going to try a month."

It's that sort of age-old adage of "a day at a time," but this time, I took it very seriously, because I was trying to work towards him, what he did. I couldn't get sober for him, but he was a part of my decision to get sober, and I've been sober since Aug. 23, 2015. And it is crazy what has happened since then, once I stopped putting substances in my body. I mean, I could not have written this book if I was drinking. There is no way. I would have blown through every edit deadline imaginable.

On finding her artistic voice and professional path in the years since her father's death

It's painful that so much of my life and in making films has taken place after he died, and at an exponential rate. My boyfriend at the time said, "You're always asking your dad for advice, like, do you ever just wait a beat and think about what you have to say before asking him?" And I thought that was really insulting. And I was like, "Well, if you had access to David Carr, how could you not use it?" ...

But just being able to call him and ask him a question — I mean, he was brilliant. ... When I no longer had that, yeah, the only voice I could really listen to at that moment was myself. And so I think that he had to leave and pass away in order for me not to rely so heavily on him. But ... I would completely rather [have] him be here and me have no work. I think that it is the most profound loss I will ever experience and nothing that has happened outweighs the pain of him being gone.

Roberta Shorrock and Mooj Zadie produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the Web.

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))