Part two of a two-part series. Read part one here.

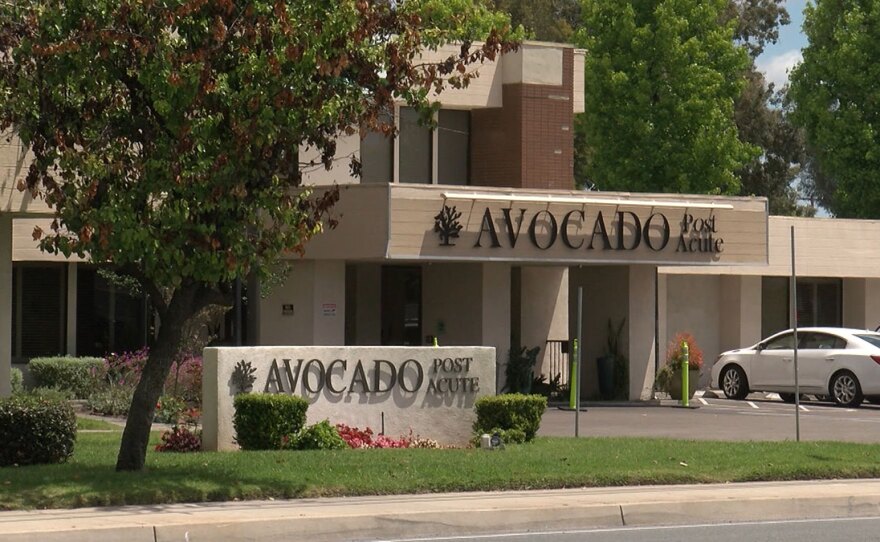

When paramedics tried to revive 66-year-old Irma Easton in her room at Avocado Post Acute nursing home on June 8, they found several powdered doughnuts blocking her airway.

A nurse at the El Cajon facility had given Easton a pack of the doughnuts from a vending machine, then left her alone to eat them. But Easton was a diabetic with a history of choking and she needed her food mechanically softened before she could eat it.

Despite the paramedics’ efforts, Easton choked to death on those doughnuts.

“She didn't have to die this way,” said Easton’s daughter Beatriz Berrios. “There are trained medical staff there. What are they doing?”

There are trained medical staff at the for-profit skilled nursing home. But not nearly enough highly trained nurses, according to a KPBS review of Avocado’s financial reports.

The review, done with the help of lawyer Ernie Tosh — who is a nationally recognized expert on senior care facilities’ finances — shows Avocado has failed in recent years to provide the level of registered nursing (RN) care expected by regulators.

For example, records from the first quarter of 2018, the most recent that are publicly available, show that based on levels of care Avocado is reimbursed for by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the facility short-changed its residents 184 hours of cumulative registered nursing care per day.

The 2018 discrepancy was part of a pattern.

Avocado shorted its residents more than 170 hours in registered nursing care per day in both 2016 and 2017, according to the independent analysis by Tosh.

Avocado’s lawyer Jon Cohn argued in a written statement to KPBS that the facility’s staffing ratios of registered nurses are in line with California and national averages.

But he did not address why the facility had not met expected staffing levels of registered nurses published by CMS for the years 2016 through the first quarter of 2018.

Registered nurses are considered the heart of nursing homes. They do patient assessment, detect infections and create care plans.

“If you don't have (registered nurses), your health care system breaks down in a nursing home,” Tosh said. “You will kill people.”

Unmet needs

Along with the lower-than-expected registered nurse staffing levels, Avocado’s complaint history shows the facility consistently falls short in its responsibility to care for residents.

From 2017 through Oct. 5 of this year, 462 complaints were filed against the nursing home, according to the California Department of Public Health (CDPH). Fifty-six of those complaints were filed this year alone, more than four times the statewide average.

Over the years, inspectors have cited Avocado for lax infection control, abuse of residents by other residents and staff, poor supervision, falsifying records and failing to keep the facility free of hazards.

Cohn, Avocado’s lawyer, said many of the complaints are self-reported and that the facility can be expected to have a relatively high number of complaints because it is much larger than most nursing homes.

“The 256-bed facility nearly triples the state average bed capacity,” Cohn wrote. “Given the large size of Avocado, it logically follows that it will have more incidents to report.”

But some experts said Avocado has a high number of complaints even when factoring for size. They add that the federal government pays Avocado to staff properly to treat complex patients.

“The facilities are supposed to meet the needs of their residents regardless of size and to have enough staff to do that,” said Charlene Harrington, nursing professor emeritus at UC San Francisco.

And so far this year, among nursing homes in San Diego County, Avocado has had the second highest number of residents who tested positive for COVID-19, according to the CDPH.

Cohn said in a written statement that after aggressive COVID-19 testing, employee screening, contact tracing, segregating sick residents and banning visitors, Avocado has nearly stamped out the virus.

“It’s important to note that because of the changes and protocols we’ve instituted, we have been COVID-free except for newly admitted COVID-positive patients who have been treated and released from hospitals,” Cohn wrote.

RELATED: San Diego Nursing Homes With Most Coronavirus Cases Have Long Complaint Records

But experts said Avocado’s voluminous complaint and coronavirus history still suggest residents’ needs are largely unmet.

“The core issue is that there’s inadequate staffing in this facility,” said Brian Lee, executive director of the Texas-based nonprofit Families for Better Care. “The residents end up suffering.”

Tosh said the chronic understaffing of registered nurses in for-profit nursing homes is a nationwide problem.

The facilities at times cover up shortages of registered nurses by overstaffing lower-level positions, including licensed vocational nurses (LVNs) and certified nursing assistants, he said. Though this practice runs afoul of federal and state laws banning LVNs from doing RN work, it can translate into big savings for the facilities.

By understaffing registered nursing care, Tosh calculated that Avocado has saved $1 million or more annually from 2016 through 2018.

Yet, financial disclosures show that Avocado earns enough money from taxpayer-funded federal reimbursements to cover its nursing shortfall and still make an annual profit that is well above nursing home industry averages, Tosh said.

Avocado has brought in more than $3 million dollars in profits in both 2017 and 2018, which Tosh said is triple the earnings of a typical for-profit nursing home.

“Clearly, when you're making three to three-and-a-half million dollars in profit, you could staff properly,” Tosh said. “This is not a facility that can stand up and say, `We didn't have the money to do it.’”

The documents reviewed by KPBS were certified as accurate by Avocado management with the understanding that inaccurate reporting could result in civil and/or criminal penalties.

While Avocado filed records with the CDPH showing it understaffed registered nurses, the facility actually told federal regulators it overstaffed nursing care.

By federal law, nursing homes must annually report how much care patients receive. The unit of measurement they use is the number of hours per patient, per day.

In 2017 and the first quarter of 2018, Avocado told CMS regulators that each of its residents received 5.2 hours of total nursing care per day. That’s 18% over the agency’s “expected” level of care.

“5.2 screams that whoever filled out that form either made a monumental mistake in calculating their numbers or that was outright fraud,” Tosh said. “Nobody has five or higher in actual staff. And when you look at their deficiencies it makes no sense.”

Tosh’s calculations show significantly lower staffing. In 2017, Avocado residents received at most 3.5 hours of nursing care a day. In 2018, number topped out at 4.5 hours of nursing care per day.

Avocado’s lawyer said one reason for the discrepancy is that the 5.2 figure is based on a “snapshot that covers about a month of data” for those years.

But a KPBS review of the records from that timeframe found no instances of Avocado staffing its nurses at a level of 5.2 hours per patient per day.

Crying poverty

Understaffing at nursing homes was a key issue during a hearing held by State legislators in June. They were seeking answers on why nearly half of the state’s COVID-19 fatalities were made up of elderly people living in senior care facilities.

Even though a Kaiser Health News analysis of federal records showed that nursing homes across the country couldn’t follow basic infection control rules before the pandemic hit, a California industry lobbyist told lawmakers they are not to blame for spiraling coronavirus cases at the facilities.

“Support this industry,” said Craig Cornett, president of California Health Facilities, a trade group for nursing homes via a Zoom call. “Support this profession with financial resources. We are almost 100% government paid. The Medi-Cal rates for nursing homes have historically been very inadequate.”

But those who study the skilled nursing facility business say it has been lucrative for investors. The SeniorCare Investor, which gives Wall Street investors “market intelligence,” put nursing homes at a near-peak value in the first quarter of this year.

“Occupancy was improving across the seniors housing sectors, development had slowed to near sustainable levels in many markets, and a faith that demographics could make nearly any community successful in the coming decade caused per-unit/bed prices to soar,” the report said.

There has been a long-standing disconnect between what nursing home lobbyists, owners and investors tell the government and actual industry profitability, advocates said.

“They wouldn't be in the business," said Mike Dark, staff attorney for California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform. “They wouldn't be living in Beverly Hills and they wouldn't have six cars in their driveway.”

Dark said the industry has monopolized legislators’ ears because the other side — people, who live in nursing homes — are too feeble to demand better.

“A lot of people in nursing homes have dementia,” Dark said. “And so there's just not a lot of political ground to be gained for politicians, local or statewide, by appealing to a nursing home audience.”

Search for solutions

Filing lawsuits against nursing homes to spur reform hasn’t resulted in much industry-wide change.

“It doesn’t put a dent in their profits,” said Tosh, who has filed hundreds of cases against nursing homes. “It’s just the cost of doing business to them.”

Experts said the only way to improve care is to strengthen oversight by state and federal regulators through strict staffing rules and follow-up enforcement.

Tosh is also pushing for federal audits of nursing homes’ finances coupled with greater transparency.

“What that would mean is you would have to bring forward your financial documents for all of your related parties and file them so that we can then see how your related parties are siphoning the money,” Tosh said.

In a written statement, a CMS spokesperson said the agency “may review individual Medicare claims submitted by skilled nursing facilities.”

But it “does not conduct financial accounting `audits’ on nursing homes on an ad hoc basis,’” the spokesperson wrote.

CMS also cited its 2018 transition to what it calls “more accurate measure of facility staffing,” which it posts publicly as a tool for families to access as a way to assess a nursing home.

The measure includes the average number of staff at each nursing home, compared to state and national figures as well as the number of residents and beds.

“These actions have helped improve registered nurse staffing as noted by a decrease in nursing homes without registered nurse staffing for four or seven days in a quarter and an increase in facilities submitting staffing data,” the spokesperson wrote.

But lawyer Tony Chicotel, who works for the California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform, said CMS’ new reporting criteria is worse than before. Now, the agency only publishes what a nursing home’s staffing is, not what it should be.

Passing those numbers off as helpful to families is “offensive,” Chicotel said.

Meanwhile, the CDPH's investigation into Irma Easton’s choking death has not been made public.

But Easton’s daughter Beatriz Berrios said a state investigator told her that Avocado was not at fault. She doesn’t understand how the state could reach that conclusion.

“They let her die there,” Berrios said “They didn't help her in the moment that she needed most. She died in the most painful, horrible way that I can imagine.”