Let me just say up front what a pleasure it is to watch a well-crafted film in which not a word or a gesture is wasted. The Coens' No Country for Old Men (opening November 16 throughout San Diego) is such a film. You feel that every word has been chosen with care and everything from the type of boots a man wears to the cut of his hair has been chosen for a distinct reason.

In a little more than two decades of filmmaking the Coen Brothers have tackled film noir, antic slapstick, Warner Brothers style gangster film, romantic comedy, crime caper, remake, and a few things that don't fit neatly into any category. They seem to want to try every genre, and the amazing thing is that they've proven adept at all of them. For their latest film, No Country for Old Men they return to the crime milieu of Blood Simple and Fargo, but this time adapting a novel by Cormac McCarthy about a man who finds and takes a stash of illicit money, and the unstoppable thug tracking him down.

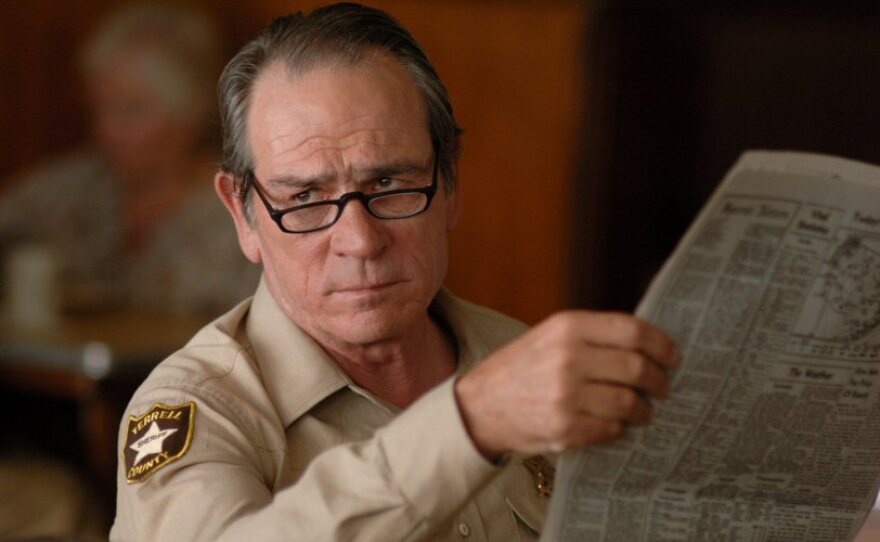

A few steps behind these two men is Tommy Lee Jones' matter-of-fact Sheriff Bell. He's like a male counterpart Fargo's Marge. Instead of her Minnesotan cheeriness, Jones serves up a patriarchal Texas practicality mixed in with a bit of old man crankiness about the way things have changed. But both Bell and Marge are essentially good, decent people not quite able to comprehend the evil they encounter in their work.

Bell begins the film with a voiceover, which presents some ideas for the audience to mull over as they watch the violent drama that's about to unfold. Bell reveals that like his father and grandfather before him, he's been a lawman since he was a young man. He tells us about a killer he recently apprehended who showed no remorse and who claimed he would do it again even if it meant he'd go to hell. Bell doesn't get this, and he confesses that he really doesn't want to meet up with something he doesn't understand. This prompts him to ask us as well as himself a question about whether this new world of killers and senseless violence is a world that he or we even want to be a part of. Consider Bell's open like a prologue (Bell will also provide the epilogue) that lays the groundwork for the themes about to be explored.

Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin delivering a lean, impressive performance that I didn't think he had in him) is a Vietnam vet. While out hunting one day, he comes across some human carnage. An apparent gunfight amongst drug dealers and their dogs presents Moss with the opportunity to walk away with two million dollars in illicit funds. When his wife (Kelly MacDonald) asks where the money's from, he simply says it's from the getting place, and instructs her to lie low while he deals with a few things. One of those things is Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem with an incongruous mop-top haircut that makes his brutality all the more disturbing). Chigurh has been hired to find the money and now he's hot on Moss' trail. Like the Terminator or the Ever-Ready Bunny, Chigurh will not stop. He comes after Moss with a ruthless determination that's truly frightening. The hunter becomes the hunted in a tense cat-and-mouse game that pits the clever and resourceful Moss against the merciless and instinctive killing machine that is Chigurh. This is a violent movie but you'll get no rush from the action here; in this film, violence is meant to disturb viewers.

When all the killing's done and the final body count tallied, Bell returns for the epilogue. He tells us about two dreams he's had about his father. His tone reflects a weariness as he ponders good and evil, choice and chance, change and a longing for the past. He wants a simpler, better time that possibly never existed. His thoughtfulness lends an unexpected sadness to the final frames of the film and gives the film more emotional weight than the Coens' usually generate. My only real complaint about the film is that it serves up a series of multiple endings. Not as bad as the LOTR: Return of the King, but just a tad too many fades to black where you think it's come to an end but then it doesn't. But I'd like to see the film again just to reconsider how those final scenes may play out a second time. A Coen film always seems to improve with multiple viewings, and No Country for Old Men might play out differently a second time around.

No Country for Old Men takes its title from the opening line of Yeats' Sailing to Byzantium. There's a certain irony to the choice. The poem describes the pain and frustration of aging, and the art (that is the imagination and spirituality) required to remain vital despite death's approach. Yeats' solution is to leave the country of the young and travel to Byzantium. But as Bell considers his old age, there really isn't any place for him to go and that gives the film a profound sadness and sense of loss. (The reference to Yeats might also prompt viewers to consider the artistry that the Coens put to use as they go on their own metaphorical journey.)

In Fargo, it was all about scale and perspective. Marge sums up the crime as being about a little bit of money. In No Country for Old Men, it seems to be about something bigger and darker, about a coming way of life that lacks soul. And that's an interesting point to make because the Coens' style of filmmaking has sometimes been criticized as being too cold and aloof. But No Country represents a more mature sense of theme, and while the Coens could never be accused of being warm and fuzzy they certainly create vivid characters that engross and compel us.

Bell's informal prologue and epilogue are unexpected bookends to what is essentially a bloody thriller with terse, Elmore Leonard-like characters. If Bell represents a decent and moral past, then Chigurh symbolizes what lies ahead. He's a soulless being unable and unwilling to feel for his victims or to take responsibility for his actions. When contemplating his next victim, he often flips a coin and asks the person to call it. It's a way of leaving their fate in their hands not his; a way of not taking responsibility for his actions. When someone suggests that he doesn't have to do what he's doing, that he can choose to stop killing, Chigurh replies that's what they all say. But it seems we have come to a point when no one in our society -- individuals, the government, politicians -- wants to take responsibility. Maybe they are not looking to a coin toss to explain away their behavior, but if they use polls, legal loopholes or national security as pat justifications for why they have no choice in the action they take, is that showing any more sense of personal responsibility than Chigurh?

If Chigurh's personality is reduced to animalistic basics of survival, then Moss is someone whose more moral instincts are muddied by the temptation of money. Money, something that Moss has never had, makes him abandon some of his moral values in order to take risky action. But his humanity (his love for his wife, his desire to help one of the injured drug dealers) makes him ultimately sympathetic but it also proves to be his undoing. Chigurh is never hinders or slowed down by such humanity.

McCarthy's novel has been praised for sharp dialogue and I don't know how much of the Coens' script is lifted directly from his text. But however the Coens have arrived at their dialogue, it zings with efficient artistry. Take a simple scene where a hired gun enters the executive office of the man who's just hired him. He takes a seat and is reprimanded for doing so. His response to the executive is succinct: "You strike me as a man who wouldn't want to waste a chair." That scene could have been a total throwaway, nothing more than plot exposition. But that brilliant but absolutely simple line says so much about the situation and the two men. The Coens, more so than any other contemporary filmmakers that I can think of, have an old school sense of character. There is a richness of character detail -- in both the dialogue and the type of actors that they cast -- that makes even the smallest character memorable. That's the kind of richness we used to find in old John Ford or Howard Hawks or John Huston films. In No Country for Old Men, the Coens take care in casting even a bit part of a woman at the trailer park where Moss lives. She is a large Texas woman who's strictly to the point. When she concludes that she has given Chigurh all the information she has, we get the feeling that even he understands that no amount of pressure, threats or torture would change her answers. She is the immovable object to his irresistible force.

As with all their films, No Country for Old Men is impeccably crafted: from Roger Deakins' clear-eyed images of both the interior and exterior landscapes of the Tex-Mex region to Jess Gonchor's drab, Walmart influenced production design to the careful blend of work from sound designer Craig Berkey and composer Carter Burwell, everything has a sense of crisp precision. I'd compliment editor Roderick Jaynes as well but he appears to be a sly alter ego for the Coens themselves. As writers, editors and directors, they are able to instill their vision on every frame of the film. Their attention to detail is evident early on in a scene where Chigurh kills a deputy. He strangles the man as they lie on the ground, with the deputy frantically struggling for his life. We hear the annoying squeaking of his shoes scraping on the linoleum tiles, and leaving a death trail of scuff marks across the floor. There is something both darkly funny and deeply tragic in the way those scuffmarks represent the deputy's passing. The film returns the Coens to the type of violence they did so well in Blood Simple --it's abrupt, often shocking and tends to be at close range.

No Country for Old Men (rated R for strong graphic violence and some language) is one of the best films this year, and the best film from the Coens since Fargo a decade ago. Go out and see this and you'll have something to be thankful for this holiday. (But note, it's not for those easily offended by violence.)

Companion viewing: Blood Simple, Fargo, A Simple Plan, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada