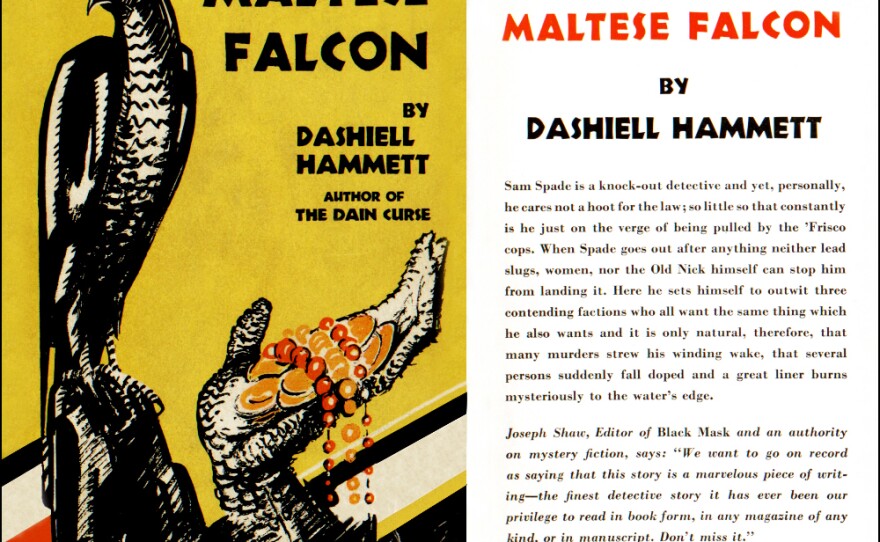

The Noir Book of the Month Club officially launched last month with Dashiell Hammett's "The Maltese Falcon." Guest blogger D.A. Kolodenko returns to discuss this month's "I Wake Up Screaming." Give the blog and the book a read before joining KPBS Cinema Junkie Beth Accomando for the film adaptation of "I Wake Up Screaming" on Feb. 25 as part of the Film Geeks SD new series Noir on the Boulevard.

Welcome back to our investigation of the books behind the films in the Noir on the Boulevard film series. On February 25, we’ll see “I Wake Up Screaming,” a rare, early A-list crime drama from 20th Century Fox, with stars Victor Mature and Betty Grable. The film was made and released in 1941—the same year as our January film, “The Maltese Falcon”—and based on pulp magazine stalwart Steve Fisher’s popular novel of the same name, released earlier that year. But before we dive into the most compellingly titled novel of the early noir cycle, let’s revisit the questions raised and left open in the last post about “The Maltese Falcon.”

“He went like that,” Spade said, “like a fist when you open your hand.” – from The Maltese Falcon

First: What’s with the Flitcraft story? Though Huston filmed the novel religiously, making almost no changes for the screen adaptation, Spade’s story about former client Flitcraft didn’t make it in. This is understandable because it comes out of the blue and, for all its weirdness, has a mundane lack of drama and no clear purpose in relation to the main events of the novel.

About a third of the way into the story, in chapter seven, detective Sam Spade sits with Brigid O’Shaughnessy at his apartment where they’re preparing to meet the shifty, black-bird hunter Joel Cairo. Spade uncharacteristically tells a brief story about a case he worked on years ago in Tacoma, Washington. Spade was hired by a woman whose friend may have spotted her husband, Flitcraft, in nearby Spokane—five years earlier, he had disappeared without a trace. Spade tracks down Flitcraft and gets an explanation for his disappearance. One day, he had just walked away from his life and all its trappings of American success—happy family, good job, a big house in the suburbs, and a sizable fortune—after a beam from a construction site had fallen to the sidewalk and just missed crushing him. Flitcraft had taken the randomness of his survival as evidence of the randomness of everything and decided to randomly start a new life; if the Universe is unordered, what difference is made by his sudden upheaval? But Flitcraft eventually starts over in nearby Spokane—and ends up with a new job, family, and life nearly identical to the one he’d abandoned.

It’s a mystery within a mystery, but not a whodunit; the mystery is, as novelist Jim Nelson puts it, “what the story means and why Spade is telling it to O’Shaugnessy.” Analyzing the Flitcraft case has been elevated to the level of a perennial philosophical enterprise in film studies: it’s been examined through the lens of everything from the existentialism of Sartre to the story of Job.

The beam’s near destruction of Flitcraft is evidence to him that the way one lives really doesn’t matter—what one chooses to do seemingly has no relationship to when and how one will die. But once the near-death incident has passed, Flitcraft ends up living the same sort of life he led before, suggesting that even if we try to escape fate, in spite of life’s seeming randomness, we may yet, to an extent, have a determined path or nature.

Spade may be warning O’Shaugnessy that he knows she’s untrustworthy and will never change. More likely, Spade is hinting that as a detective, no matter whatever distractions might come in his path, he’s determined to solve his partner’s murder. Either way, Hammett knew the novel was philosophical and told his publisher so; it may even be the case that he dropped the Flintcraft story in there without having a deeply considered specific intention. Maybe he liked the puzzle of the beam dropping into Flitcraft’s life as a parallel for the puzzle of the black bird dropping into Spade’s. These random motivating macguffins are “The stuff that dreams are made of”—symbols of the danger of attachment but also the unknowability of fate—onto which each of us imposes meaning.

Is there room for love at the heart of film noir?

Reading Spade’s parable as a signal to O’Shaugnessy that nothing will truly divert him from his path also suggests an answer to the second question I posed in the last blog post: Did Spade love O’Shaugnessy? Almost everyone says yes. When he decides to send her up for killing Archer, she accuses him of having played with her all along, of having never loved her, to which he responds, “I think I do. What of it?” And after weighing that maybe she loves him and maybe he loves her against the potential prison or death that awaits him if he lets her go, he says he’ll get over being sorry as hell and that the rotten nights will pass. After all, when a detective’s partner dies, he has to do something about it.

This is what many take to be the romantic central conflict of the novel—Spade has feelings for O’Shaugnessy, whether it’s love or some level of attachment, and it pains him to trick her and hand her over for what is likely to be a long time in prison, though he knows he must.

But noir iconoclast William Ahearn sees it differently: he argues that everything Spade does is calculated and designed to solve Archer’s murder. Ahearn doesn’t buy that Spade ever loves O’Shaugnessy. After all, Hammett wrote that Spade was the idealized detective that all the detectives he knew at Pinkerton’s aspired to be: a tough, unsentimental strategist always one step ahead of everyone else. Consider the cruel way Spade tells her he hopes they don’t hang her by her pretty neck and that if she gets out in 20 years, she should look him up. So if he doesn’t love her, why tell her he might love her? Why this last bit of equivocation or duplicity before sending her to her fate? Is it a tiny modicum of mercy or just one more little taste of her own medicine?

Fisher and the Black Mask evolution

If there’s any question of whether the 1941 film version of “The Maltese Falcon” is a true noir—after all with only a couple exceptions, it has the stagey, simple direction of a 1930s filmed play, and little of the expressionism and oneiristic qualities that are typical of film noir—there’s no question that “I Wake Up Screaming” is a noir. If it were a film of the same caliber, it would certainly be acknowledged more often as an important early entry in the cycle. Likewise, if the novel held up as well as Hammet’s, Fisher’s unquestionable importance to the development of film noir would be more widely recognized.

If you’re reading the books along with me, you already know that Steve Fisher was not the master of description and plotting that Hammett was. Fisher was from the other school of crime writing: unlike Hammett, he didn’t approach the pulp crime genre with major literary ambitions. He was a committed workhorse driven primarily to make a living as a writer, and succeed at this he did, authoring over 500 stories for pulp and mainstream magazines, at least 13 novels, 53 screenplays, and 200 TV episodes, churning out a ton of work until the end of his life.

So quantity over quality, yes—but Fisher defended his work, said he put himself into, and was proud of, everything he wrote. Current publisher of Black Mask Magazine, Keith Alan Deutsch, argues that Fisher was “a master of dark, psychological thrills” whose talent was not only in being prolific but also in exploring the inner lives of his characters and in crafting moody, suspenseful scenarios, particularly in his work for the screen. Certainly the first-person confessional tone and emphases on the troubled interior lives of multiple characters in “I Wake Up Screaming” are a departure from the detached omniscience of Hammet’s narrator, who doesn’t seem to know what Spade is thinking any more than the reader does.

In fact, Fisher considered himself at the center of a “subculture revolution” in the Black Mask mystery universe that occurred in the late 1930s when Fanny Ellsworth took over for Joseph Shaw as editor of the magazine. Shaw had shaped the magazine’s hardboiled, objective style popularized by writers like Hammett; but Ellsworth leaned toward the more subjective, psychological crime stories by writers like Fisher and his better-known friend Cornell Woolrich (Fisher even named the perverse and obsessive detective Ed Cornell in “I Wake up Screaming” after Woolrich). Woolrich’s novels and stories, with their creepy, sinister, nightmarish mood and contrived and often fantastically implausible plots have been adapted into films noir more than any other writer’s (though Woolrich himself never wrote a screenplay), including Hitchcock’s “Rear Window,” and his own tragic life amplified his legend—so it’s understandable that his work has overshadowed Fisher’s in the noir universe.

But “I Wake Up Screaming” was compelling enough to be filmed twice (the second time in 1953 as “Vicky,” an equally disturbing though less shadowy film) with both screenplays penned by longtime studio writer, Dwight Taylor, and the 1941 version has recently becoming more rightfully recognized as, if not the first film noir, the first film that is nearly universally considered a noir. And though the majority of Fisher’s stories and novels aren’t read today, his screenplays hold up: for the 1947 film version of Raymond Chandler’s “The Lady in The Lake” (he replaced Chandler, who was notoriously alcoholic and not thrilled with working in Hollywood); “Dead Reckoning” (1947) with Humphrey Bogart; “Song of the Thin Man” (1947), the last in the series based on Hammett’s characters; “The Lost Hours” (1952); “The City That Never Sleeps” (1953); “Hell’s Half Acre” (1954); “I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes” (1948) based on a story by his pal Woolrich; and a personal favorite of mine, “Roadblock,” the 1951 “B” noir with Charles McGraw and Joan Dixon, about a guy who goes bad for a girl who goes good for him, based on a story by Daniel Mainwaring, whose “Build My Gallows High” we’ll be reading in August.

A brief biography of Steve Fisher

Fisher didn’t start his writing career in Hollywood, but he did grow up in Los Angeles. He was born in Marine City, Michigan in 1912, but his mother was an actress, so it may be that her ambitions brought them to L.A. He was enrolled in a military school but dropped out to join the Navy. According to Deutsch, he likely served on a submarine. As a teenager, he sold his first story to a magazine and while in the Navy wrote for both US Navy and Our Navy magazines; he continued to write for Navy magazines in L.A after his discharge in 1932. His first non-Navy pulp stories appeared in erotic publications like “Spicy Mystery,” but Fisher relocated to New York and broke into the detective pulps, where his stories appeared in magazines like “Clues,” “Detective Fiction,” “Thrilling Detective,” “The Shadow,” “Phantom Detective,” “Black Mask,” “Crime Busters,” “Detective Romances,” “The Whisperer,” “Thrilling Adventures,” “Dare Devil Aces,” “Dime Sports Magazine,” and others.

In the late 1930s, his Navy-themed adventure and romance stories began appearing in higher-paying magazines like “Liberty” and “Cosmopolitan.” His literary agent in New York helped him place stories and publish novels, while his agent in Hollywood helped get his stories optioned for films. His first major film success, “I Wake Up Screaming” was purchased for $7,500 just after it had been serialized in “Photoplay-Movie Mirror,” and stands as his most important work in a prolific career that spanned five decades.

The novel and its place in noir history

Unlike the consistency between novel and film in “The Maltese Falcon,” screenwriter Dwight Taylor—co-founder and one-time president of the Writer’s Guild of America—made significant changes to the story for the film, toning down the sex and violence, of course, and even toning down the title to “Hot Spot,” though it was thankfully changed back to “I Wake Up Screaming” before its release upon the insistence of the cast. The most significant change was the setting: the story was moved from Los Angeles to New York because the head of 20th Century-Fox, Daryl Zanuck, had banned representations of Hollywood in the studio’s films (having risen up in the studio system during the scandals of the 20s and early 30s and through the new era of censorship under the Hays Code, it’s likely that Zanuck wanted to avoid contributing any fuel to the fire regarding Hollywood’s already tainted reputation).

This was unfortunate because the cynical details Fisher provides about how stars were constructed in the Hollywood studio system, and even the scenes set in commissaries, backlots, and Sunset Strip nightclubs have a realistic insider quality that place the book squarely in the tradition of the midcentury dystopian Los Angeles novel that includes Nathaniel West’s “Miss Lonelyhearts” and “Day of the Locusts,” Jon Fante’s “Ask The Dust,” Horace McCoy’s “They Shoot Horses Don’t They,” and Raymond Chandler’s “The Long Goodbye” and “The Little Sister.” And Taylor’s relocation of the story to New York didn’t replace the specificity of Hollywood expose with details about what it takes to make it in New York. But it did force onto the film the limitations of the Fox backlot and soundstage, which lends it a claustrophobic mise en scene that veteran director Bruce Humberstone and Fox cinematographer Edward Cronjager used to create the high-contrast, shadowy atmospherics that become the template for Hollywood noir over the following decade.

Ironically, the book’s trajectory is in the other direction: Fisher’s main character Pegasus is a successful New York playwright who has relocated to Hollywood to make it in the movies. Peg seems to be a stand-in for Fisher—not as cynical as Raymond Chandler, but a bit of a hardboiled realist; at the same time, he has some of the fresh enthusiasm of a Barton Fink, if not the idealism and naiveté. Immediately upon his arrival in Hollywood to start work on his first studio contract screenplay, Peg discovers an attractive secretary at the studio named Vicky, and uses the pat pretense of turning her into a star to put the make on her.

All it really takes is a couple zombies at Don The Beachcomber for Peg to spend the night at Vicky’s apartment, but he’s smitten and decides to follow through by enlisting some producers and an actor to help. Peg self-consciously describes her rise to stardom in a montage, one of the more interesting stylistic conceits in a novel full of hackneyed conventions, such as too-obvious self-incriminations (Vicky gives him the key to her apartment; he writes that if she loved the actor Robin Ray, he’d kill her), and cringeworthy anachronisms (downtown L.A. is where “blondes taxi-danced with gooks”; Vicky’s sister Jill gets a gig as a studio extra and her civil war dress makes her cleavage a “milky-white canyon”; etc.) Peg also has the hots for Vicky’s older sister, Jill, a less ambitious but contented nightclub singer; not long after Vicky is out of the picture, Peg makes out with Jill and then tells her he doesn’t love her. He’s less of a creep than the obsessive cop who tries to make his life a living hell, but one gets the impression that Fisher is unable to see that his protagonist’s limitations make him far from sympathetic, even if we do want him to escape the wrath of Ed Cornell—after all, Peg didn’t kill Vicky, he just exploited her.

You’ll find that the movie replicates the basic plot and character dynamics of the novel, and handles particularly well the innocent-man-on-the-lam section, which is where the novel picks up considerable speed. But there are a number of differences: Ed Cornell is much less sadistic a monster in the film, even if he’s played by the reliably scary Laird Cregar—the still relevant critique of cops who’ll stop at nothing to get their man notwithstanding. Vicky becomes a waitress instead of secretary and turns out to be a good singer out of the blue (it was Jill who was the struggling singer in the novel). Vicky’s meteoric and heady success takes her to Hollywood in the film—offscreen, of course. And Peg becomes Frankie Christopher, a publicist instead of a writer—watch carefully for a subtle tribute in the film to the character’s original name.

There’s a fun San Diego angle in the novel: When Peg’s group of picture-biz Pygmalions pushes Vicky on the public, they concoct a phony back story for her: her father is a San Diego Naval Officer; she was a swanky debutante raised on Coronado, where one of Peg’s producer friends discovered her at a party. Equally fun are the many descriptions of Los Angeles that are clearly of another time: “Couples lay in the grass in MacArthur Park, watching the cars stream over the Wilshire Bridge.”

A final note on the book: you may wonder why a book from 1941 namedrops Marlon Brando or a movie like “Beatnik in a Hot Rod.” Apparently the publisher saw an opportunity to update the novel in 1960 for a new generation and hired Fisher to revise it. Fisher has received some criticism for this and rightfully so; it’s a sloppy and unnecessary revision, where men still show up to nightclubs in top hats and derbies, but where Ginger Rogers in the original has been replaced with Jayne Mansfield. Fisher must’ve been paid peanuts. It’s difficult now to find the original—all reprints with the exception of the Black Mask reissue have been of the 1960 version. But it’s worth owning the original, which doesn’t feel like such a disjointed hodgepodge of eras.

Ultimately, “I Wake Up Screaming” stands as a defining moment in the shift from the objective to subjective in crime fiction. And in spite of its flaws, it’s a solid whodunit that keeps you guessing which of the characters is the killer—a lot of them have motives. The details of old Hollywood fascinate, and the cynicism toward the cruelty and sexism of the movie business and law enforcement feel as relevant as ever. But what makes this novel noir fare are Vicky’s corruption by fame; the multiple male characters’ obsession with her; Peg’s inexplicable admixture of lust and resentment toward Jill; and the corruption of the movie business and police force. In short, the psychological turmoil of the characters and the sense that urban modernity offers no solace or justice make “I Wake Up Screaming” an undeniable early blueprint of American film noir.

See you at the Digital Gym Cinema on Sunday, February 25 at 1 p.m. for “I Wake Up Screaming.” Next month: Graham Greene’s “This Gun For Hire” (1942). Get your copy and I’ll meet you here next month.

D.A. Kolodenko: Musician. Waiter. Warehouse worker. Print shop manager. College professor. Lecturer. Columnist. Journalist. Editor. Science writer. Advertising copywriter. These are some of the things I’ve been. Detective. Hitman. Embezzler. Boxer. Prison inmate. Fugitive who escapes by running into a tunnel or climbing up something. These are some of the things that the books and movies I like have taught me to avoid being.