This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

Uber and Lyft drivers in California have been fighting for years for higher wages and better working conditions — in the streets, before state lawmakers, in court and at the ballot.

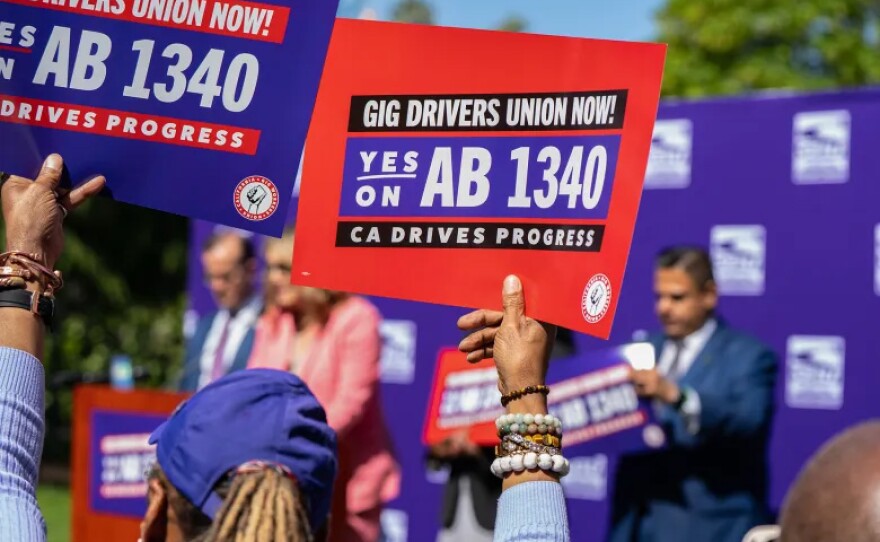

Now, a bill making its way through the state Legislature would allow ride-hailing drivers to unionize.

If Assembly Bill 1340 passes, California would become the second state to give ride-hailing drivers the right to collectively bargain. Massachusetts was the first to do so after voters there approved a ballot measure last year.

The ride-hailing companies oppose the California legislation, saying it goes against the “spirit” of Proposition 22, the ballot initiative they bankrolled that voters approved in 2020. It cemented gig workers’ status as independent contractors in the state. The law also limited state lawmakers’ ability to establish collective-bargaining rights for gig workers, but an appeals court struck down that provision.

Drivers and other gig workers gained some benefits when Prop. 22 passed, but their complaints continue, many of them tied to the fact that they are not considered employees. And since the law effectively leaves no state agency in charge of enforcement, many gig workers don’t know where to turn to claim unpaid wages or health care stipends, to contest getting kicked off the apps, or to get help with other problems.

Some drivers and advocates say being able to collectively bargain could address those issues. But the gig-work industry warns that would mean big changes to their business model, which would push ride prices higher and affect the availability of rides.

“We can benefit a lot from being unionized,” said Hector Lopez, who has driven for Lyft in the Bay Area for the past several years and is involved with the group Gig Workers Rising. “It might be the only way to get fair wages.”

A group that represents Uber and Lyft has said drivers in California earn an average of $37 per “active” hour, while research from the UC Berkeley Labor Center found that the average pay for drivers, including tips and taking their entire working shifts and expenses into account, was $9.09 per hour.

Another common driver frustration is limited communication when they need help. Drivers have to use the Uber or Lyft app to message back and forth with a company representative, or in some cases talk with them on the phone. But Lopez remembers being able to get help at a Lyft Hub, a physical location staffed with human beings he could talk to. Those hubs closed down a few years ago.

“We could have a union, which would have an office, where we could get help face to face,” Lopez said. “That’s something that’s really big that they took away from us.”

Not all drivers will be on board. There is “a healthy suspicion” around unionizing among California drivers who say they value their status as independent contractors, said Sergio Avedian, senior contributor for the Rideshare Guy, a YouTube channel popular with gig workers.

But he said many drivers also “often express frustration about a lack of representation and leverage, especially when it comes to deactivations, rate cuts and algorithmic transparency.”

What the bill would do

The proposal before the Legislature would give ride-hailing drivers the right to form and join a union with which the gig companies would be required to bargain in good faith.

It would also require ride-hailing companies to submit lists of drivers and other driver information to the state’s Public Employment Relations Board every three months starting in 2026.

The Protect App-Based Drivers & Services Coalition, an industry group that includes Uber, Lyft, DoorDash and Instacart, opposes the legislation, as do various chambers of commerce and business groups.

In a letter to lawmakers in July, the group said the bill’s requirement that companies submit driver information to the state — which would give a potential union a way to directly reach a dispersed group of workers — is “a dangerous violation of driver privacy” and could result in unwanted texts, phone calls and even visits to drivers.

Different drivers groups are expected to vie to be the sole bargaining union of ride-hailing drivers statewide. But provided a group can get 10% of active drivers to approve it as a representative, it would be able to access driver lists, according to analyses of the bill by legislative committees. Each group would be prohibited from sharing that list with third parties.

Nicole Moore, president of Los Angeles-based Rideshare Drivers United, supports the bill’s disclosure requirements. “Right now the state has no idea how badly we’re being paid,” she said. “We could tell you, but that’s anecdotal. We need data.”

Uber spokesperson Zahid Arab said the bill would mean increased costs because of administrative and compliance burdens, and the fact that the company would have to negotiate with a union over pay and benefits. The industry group said if drivers get the right to unionize, it could lead to higher costs for rides.

A Lyft spokesperson would not comment on the legislation.

The bill, co-authored by Assemblymembers Buffy Wicks of Oakland and Marc Berman of Palo Alto, both Democrats, is set for a hearing before the Senate Appropriations Committee on Aug. 18.

What’s happening in Massachusetts

In Massachusetts, Uber and Lyft drivers won the right to unionize months ago and are now working to make a union a reality.

Chiem Klot, who has been driving for Uber for a decade, is trying to organize Boston-area drivers. He says his pay “gets worse and worse every year.” He said he used to be able to make $300 or $400 a day, and is now driving for 12 hours a day and making about $200 a day.

“There are over 80,000 (ride-hail) drivers in Massachusetts,” Klot said. “They all work so hard to make very little money. A lot of them still don’t know they’re allowed to unionize. Some of them are also scared to — that Uber might retaliate.”

The Massachusetts App Drivers Union is a joint effort of Service Employees International Union 32BJ and the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers.

Gabe Morgan, executive vice president of SEIU 32BJ, said through a spokesperson that thousands of drivers in Massachusetts have already signed unionization cards, and that besides fair compensation, drivers deserve transparency.

Will sectoral bargaining work?

Sectoral bargaining, or negotiating as a group within a certain occupation, has worked in certain places and industries, such as in Los Angeles, where hospitality workers have won wage standards and benefits, said Katie Wells, a tech and labor expert who co-wrote “Disrupting D.C.: The Rise of Uber and the Fall of the City.” But Wells said she’s concerned that in the ride-hailing industry, sectoral bargaining may not lead to real change.

That’s because the big players in the gig economy have fought to keep change “superficial,” Wells said. She pointed to Prop. 22, which among other things promised California gig workers health care stipends. But a union-backed survey showed few gig workers actually qualify for or use the stipends, which are not extended to those who get public health benefits. The survey also found that 29% of gig workers surveyed were on Medi-Cal, California’s health insurance program for low-income people and those with disabilities. The companies have not released exact numbers about how many workers receive the stipends.

Sectoral bargaining “could work, but it has to be done well,” said Laura Padin of the National Employment Law Project, a research and advocacy group for low-wage workers. She said drivers “are subject to a lot of control of the companies” and should be covered under the National Labor Relations Act, but they are not because they’re not considered employees. “In this political environment, it may be the best we can hope for,” Padin said.

Federal lawmakers have been trying for years to improve gig workers’ working conditions. The most recent proposal was introduced last week by Sens. Brian Schatz of Hawaii and Chris Murphy of Connecticut, both Democrats. It would require gig companies to disclose more detailed information about wages and fares to drivers and consumers; cap companies’ cut of each ride’s fare at 25%, meaning 75% would go to drivers; and more. Other proposed federal legislation that would help strengthen workers’ right to organize has languished for years. So other governments are trying to step in. At the state level, besides California, Minnesota and Illinois are also considering bills to give drivers collective-bargaining power.

But even if drivers are able to band together and unionize, they would still likely have to deal with more obstacles, experts say.

“When drivers are able to organize and win labor standards through public policy directly, Uber tries to fight it,” said Mariah Montgomery, national campaigns director for PowerSwitch Action, a network of advocacy groups. She mentioned what has happened in New York City, where drivers won minimum pay rates that began in 2019.

Last year, Bloomberg reported that Uber and Lyft were using a loophole in the law and systematically locking drivers out — preventing them from finding work on the apps — during certain periods. Last month, the city’s taxi commission established new rules ordering the companies to give drivers 72 hours notice before locking them out.

This article was originally published by CalMatters.