One of the first things Charlie Praphatananda did when he got out of prison was vomit. After 22 years inside, hurtling down the freeway at 70 miles an hour was overwhelming, a feeling he’d have again and again in the coming days and weeks as he learned how to send text messages, use Facebook and reconnect with his family.

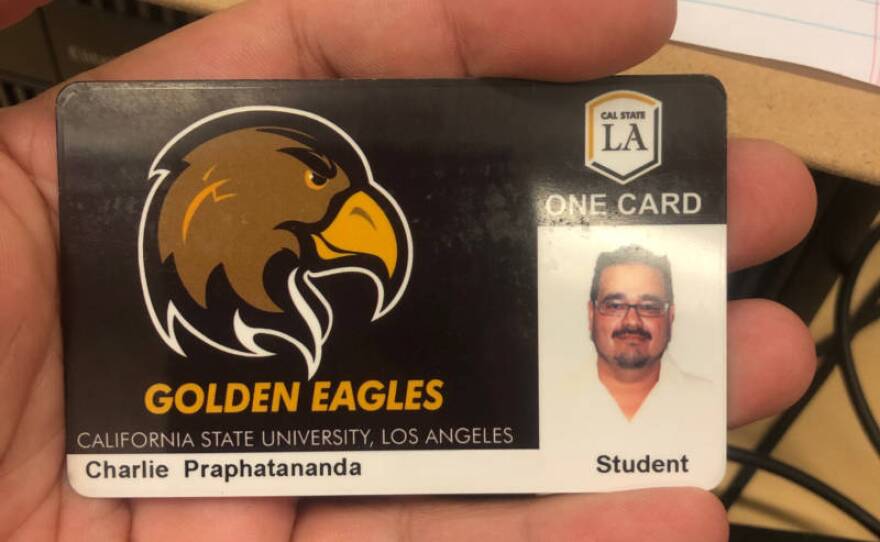

But the day he got out, he knew there was one place he could get his bearings: California State University, Los Angeles. After puking on the side of the road, he headed to campus, where he got his student ID. Though his hair was a mess in the photo, he was proud.

"They taught a bunch of traumatized people, that don't know how to communicate, how to communicate and transcend their trauma."

— Daniel Whitlow, 39, an inmate and student at the California State Prison in Lancaster

A year earlier, Praphatananda was serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole. He was also three years into a bachelor’s degree program — one of 42 men participating in an experiment that tests the limits of the public university mission to spread educational opportunity far and wide

Cal State LA’s Prison Graduation Initiative is the state’s only public bachelor’s degree program sending professors to teach behind bars. College programs like it were once far more common, and today advocates are hopeful the political winds have shifted enough to bring public dollars back to prison education.

Federal legislation that would make grant aid available has bipartisan support, and in California, a bill to open the state’s financial aid program to incarcerated students is headed to the governor’s desk.

For the time being, Cal State has made its program work, mostly on private grants. And while it has provided prisoners an undergraduate education, it’s also offered men like Praphatananda something no one expected: a path to freedom.

Transcending Trauma

Once a month, Taffany Lim makes the 70-mile drive from LA to the maximum security state prison in Lancaster, a concrete island in the high desert. Lim helped create the B.A. program here and runs it.

Since launching the first class four years ago she’s become something between a principal and a mom figure to the men in the program. They call her Miss Taffany and treat her with a sort of saintly reverence.

“They can't get over the fact that our tenure track faculty, our staff, would travel 90 minutes each way to be with them,” said Lim, senior director of Cal State LA’s Center for Engagement, Service and the Public Good.

Four nights a week, a Cal State professor teaches a three-hour class at the prison that builds toward a bachelor’s in communications. It wasn’t the guys’ first choice, but the business degree they lobbied for was off the table because they lacked the math coursework. Still, they’ve found meaning in the choice of major.

“It was a stroke of genius,” said Daniel Whitlow, 39, who has been in prison since he was 17. “They taught a bunch of traumatized people that don't know how to communicate how to communicate and transcend their trauma.”

The program lives in the prison’s A Yard, a place the men describe as a haven from the brutality of standard prison life, where, as Whitlow puts it: “We are not taught anything other than to perpetuate everything that made us into who we were at that moment when we committed our crime.” All he knew was survival, he said, until he came here.

A Yard, the Progressive Programming Facility, is a place reserved for men who’ve earned access to some of the state prison system’s richest rehabilitative services through good conduct. Here, men serving long, often life, sentences put on theatre productions, play music, train service dogs and embrace self-improvement.

Even in this context, though, they say the B.A. program is a paradigm shift.

“When I got into college, that opened my mind to something completely different,” Whitlow said. “I've grown decades in the space of three or four years. I've learned everything about myself.”

‘Public Education Is Really Our Only Option’

In the heyday of correctional education in the U.S. in the 1970s, school was seen as crucial for successful rehabilitation, and college-level courses played an important role.

"If I had the chance right now to go home or have this education, I would choose this education."

— James Cain, an inmate and student at the California State Prison in Lancaster

“There was an understanding that postsecondary education is one of the few things that really gives people enough skill to make a decent living when they get out,” said retired professor Carolyn Eggleston, who co-founded the Center for the Study of Correctional Education at CSU San Bernardino.

But as the national political climate began to change, support eroded.

“We will soon have the best-educated prison population in the world — but we will have sacrificed the hopes and dreams of hundreds of thousands of our young men and women, who always have been good citizens,” Sen. Kay Hutchison of Texas told Congress in 1993.

By the following year, Hutchison’s amendment to the federal crime bill banned incarcerated students from accessing Pell Grant aid to help pay for school.

Without that source of funding, programs began to crumble. Within a decade, the number of prisoners in college classes dropped by half, according to a 2014 study by Rand Corp.

Today, about 4% of the nation’s accredited higher education institutions teach for-credit classes in prison, according to the University of Utah’s Research Collaborative on Higher Education in Prison. Most are community colleges.

California has become a national leader in prison education since 2014, when state lawmakers opened the door for community colleges to begin teaching inside. There are now in-person community college classes in all but one prison in the state, enrolling some 4,000 students.

The corrections community, lawmakers and others, including some victim’s rights advocates, have generally been supportive of expanding higher education in prison in recent years. Those raising concerns about bringing back Pell Grants often work in prison education themselves.

Erin Castro, who runs the University of Utah collaborative and oversees the school’s in-prison college program, points out that though many more programs existed before the ban on Pell, the quality was dubious in some cases.

She fully supports lifting the ban on Pell for prisoners, with a key caveat: “Incarcerated people are in a position where they cannot participate in this notion of college choice -- they don’t have it,” she said. “So when we open the floodgates and allow institutions to access Pell money, without any oversight, we’re asking for a disaster.”

Some advocates are hopeful federal aid could help more public schools reach incarcerated students.

“Given the size of our criminal justice population and the scale of mass incarceration … our public higher education system is really our only option,” said Stanford Criminal Justice Center executive director Debbie Mukamal, who co-directs a statewide initiative to expand college opportunities for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated students.

Cal State LA’s program is the first attempt to bring the state’s public four-year university system to bear on the issue.

‘The Other Fork in Life’

When Bidhan Roy first visited A Yard as a volunteer, the Cal State English professor heard from inmates who had amassed a collection of associate’s degrees and were hungry to continue their educations. As the number of students working towards associate arts degrees behind bars in California has grown, so has the demand for bachelor’s programs.

But Roy has also come to believe the degree holds special meaning for his incarcerated students because most of them went to prison at the age other young people went away to college.

“In a kind of symbolic way it represented the other fork in life. But also the fork for most of them, that was never an option,” he said.

For Praphatananda, education never felt like one. He said he was diagnosed with dyslexia and a learning disability in fourth grade. “School was just a constant reminder of my shortcomings and failures,” he said.

So when he got kicked out during his junior year of high school, Praphatananda didn’t care. He spent his late teenage years getting in trouble. At 20, he took part in a robbery that ended in a murder and a life sentence without parole.

After Praphatananda had exhausted his appeals, he had to face down his sentence. “You come to this crossroads where you realize that when they say life without, they mean literally you're not ever going to get out of prison,” he said, “and you have to make that choice of what you're going to do with your life.”

As he saw it, he had two options: drown himself in drugs until he ran out of money, or try to make the best of it. He opted to earn his GED, then A.A. and was one of Cal State LA’s first students behind bars.

Most of Praphatananda’s classmates in the program have similar histories, and were convicted of equally serious crimes. The sheer number of life sentences on A Yard might have discouraged a less determined advocate, but Roy is guided by a belief that education is a universal right, and foreclosing on human potential isn’t his thing.

"In a kind of symbolic way it represented the other fork in life. But also the fork, for most of them, that was never an option."

— Bidhan Roy, a Cal State LA English professor teaching inmates at the California State Prison in Lancaster

In contrast with the victims’ rights advocates of the ’90s who opposed investing in such programs, the executive director of the National Center for Victims of Crime shares that view.

“I’d rather have people who are rehabilitated and can contribute to society than people who are just rotting in a prison cell,” said Mai Fernandez. While she is quick to note she doesn’t speak for all victims, Fernandez added: “There are a lot of offenders who have severe trauma backgrounds. We need to look at them also as victims.”

‘Almost Always a Backlash’

Whether Cal State LA’s program can be scaled isn’t clear. It’s a massive logistical and financial undertaking that costs the school about $12,000 a year per student, according to administrators.

The program is part of a national pilot that allows some prisoners to once again access Pell Grants, and as more and more students begin to use those funds, administrators may be able to rely less on private money. But program coordinator Lim said basic hurdles — like finding Social Security numbers — can stand in the way of getting the funding, not to mention basic restrictions on aid that leave many inmates ineligible.

Still, a recent report from the Vera Institute of Justice estimates some 463,000 people in prisons nationwide would be eligible for Pell Grants if the ban were lifted. In California, they estimate, reduced recidivism associated with Pell access would save close to $70 million a year in incarceration costs.

Recidivism rates in California are stubbornly high: about half of people coming out of California prisons end up getting convicted of another crime — a rate that hasn’t changed in 10 years, the state auditor found, despite increased investment in rehabilitation.

"Incarcerated people are in a position where they cannot participate in this notion of college choice — they don’t have it. So when we open the floodgates and allow institutions to access Pell money, without any oversight, we’re asking for a disaster."

— Erin Castro, who oversees the in-prison college program at the University of Utah

But school is a powerful tool against those odds. A major study by the RAND Corporation found taking classes in prison cuts the chances of getting locked up again by 43%.

Eggleston, who spent over four decades studying prison education, has watched the ebb and flow of investment over the years and is heartened by what she sees today — but worries it won’t last.

“There's almost always a backlash,” she said. “We lose post-secondary first because of the idea that it's too much to give those people.”

From Prison Education to Freedom

For Cal State’s incarcerated students, the college experience has been transformational — one that allowed them to believe, often for the first time in their lives, that they held some value.

“It's been the most amazing experience of my entire life, as either a free man or as an incarcerated human being,” said James Cain, who has been in prison for 13 years. “If I had the chance right now to go home or have this education, I would choose this education.”

For the men of A Yard, education has become a kind of freedom. But it’s also led to liberation of the literal sort.

Since the program began, five students have had their life sentences commuted. Three are finishing their degrees on campus.

Charlie Praphatananda is the latest. At 43, Praphatananda has lived more of his life in prison than outside. It took him decades of good conduct and dedicated self-improvement to merit commutation, but the support of Cal State LA went a long way toward proving he should get a second chance.

“When I was in and I had life without, I had given up on trying to ever get out,” he said. “To go from that perspective to, ‘I'm out here now — I get to go to college, I get to spend time with my family, I get to work’ — that is a blessing.”