When Peter Carlson was in his first year of teaching, he decided to include comics in his classroom library.

“What I saw was transformational,” he said. “Students who were reluctant to even pick up a book that might be of interest to them would just dive in.”

Pretty soon, he said, students were bringing siblings and friends to the shelves.

“It's not just like, ‘Oh, they like comics,’” he said. “This is a community and culture of literacy that they're organically building.”

Carlson held a presentation Wednesday for other teachers looking to teach about, with and through comics. The San Diego Central Library is hosting a series of panels for teachers and librarians during Comic-Con weekend.

Susan Kirtley, a professor of English at Portland State University, led the presentation with Carlson.

“I think that often people will assume that it's so much easier to teach a comic, when in fact they're very complicated texts,” she said in an interview. “You need to think about what is the image doing, what is the text doing, what are they doing together and apart, and what's happening between the panels.”

Kirtley especially liked "X-Men" comics as a kid. But comics and graphic novels aren’t just superhero stories, she said.

“There are nonfiction comics about recovering from cancer. There are nonfiction comics about climate change,” she said. “There are also fantastic romances and action stories and science fiction. All age levels, every topic. There really is something for everyone.”

Robert Lanuza leads a Spanish language graphic novel book club at the Carmel Valley Branch Library. He uses comics to help kids — who are often learning Spanish as a third language — build their vocabularies.

“In case they can’t understand what’s going on in Spanish, the picture helps to visualize what’s going on and further cement their learning,” he said.

Plus, he said, the humor keeps kids engaged. His book club especially loves the “Dog Man” series, from “Captain Underpants” author Dav Pilkey.

“There's always some sort of joke, like a fart joke or a vomit joke,” Lanuza said. “The kids just bust up laughing.”

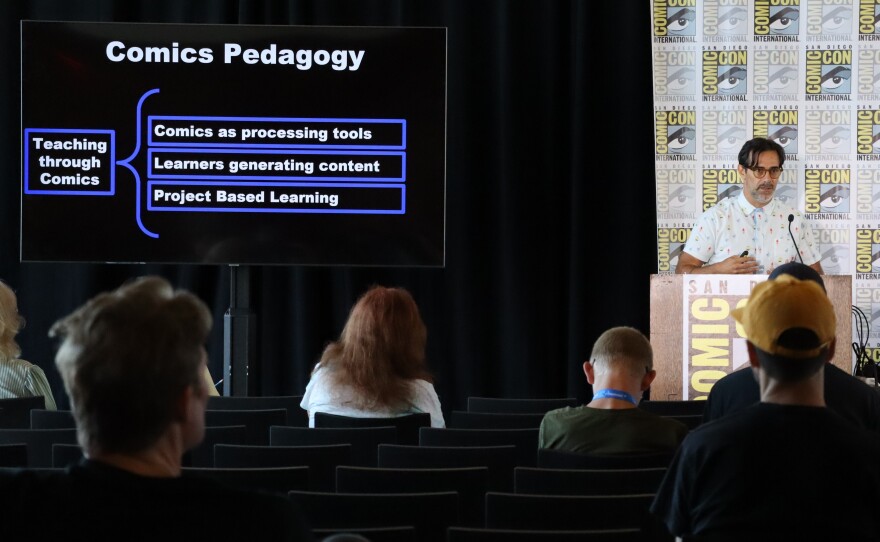

Along with reading comics, creating comics can push students to think in new ways, said artist Nick Sousanis. He runs the comic studies program at San Francisco State University and has led workshops for teachers.

“My art allows me to do things I couldn't do without it. It allows me to think in ways I couldn't think without it,” he said. “I see that for every single one of my students, not because they're great illustrators or whatever. It's because they're able to access something about how they think, which doesn't always fit into ‘left, right, left, right, left, right.’”

Teachers looking for comics to bring into their classrooms can visit comic book shops, look around and ask what kids are enjoying, Sousanis said.

Before adding comics to their curriculum, teachers should think about what they want their students to learn and feel, Carlson said. For example, he’s included Marjane Satrapi’s graphic memoir “Persepolis” in a unit about coming-of-age stories.

“Anything can be grade-level rigor depending upon the question sets that you've prepared and the tasks that you're putting in front of students,” he said.

Other panels at the San Diego Central Library will cover topics like teaching science fiction and navigating book bans.