The Yellow River snakes through northern China for more than 3,000 miles and is known as the country's mother river. Thousands of years ago, Chinese civilization grew up along its banks.

But it's also known by another name: China's sorrow. Over the centuries, its floodwaters have claimed millions of Chinese lives.

Now, though, the problem has reversed. For three years in the 1990s, the Yellow River — which 140 million people depend on for water — actually dried up before it reached the sea, due to overuse. And pollution on the river has reached horrific levels.

At the River's Source

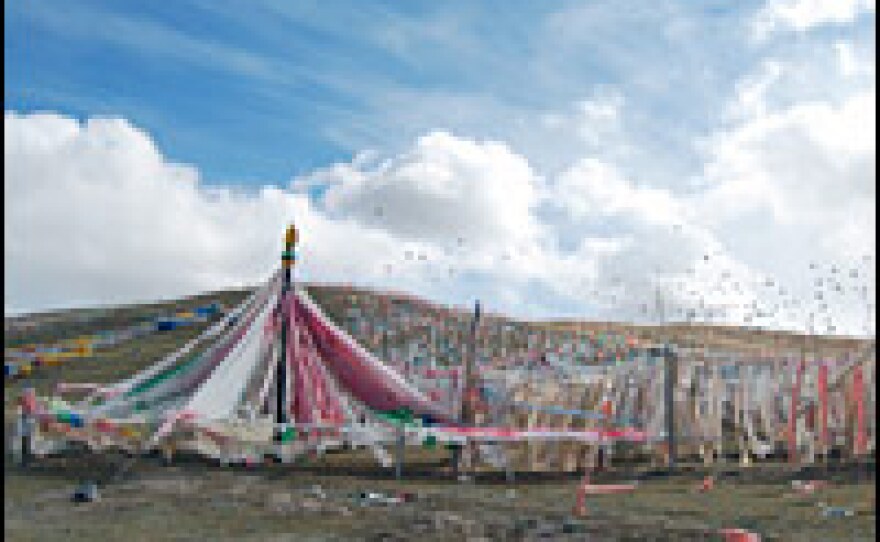

The river begins its journey across the country high on the Tibetan plateau in western China's Qinghai Province. Amid silence and pristine beauty, the river flows out of two crystal clear lakes 15,000 feet above sea level, surrounded by snowcapped mountains and grasslands. The blue sky and mountain snow are dazzling, as is the wildlife here: deer, wolves, foxes and eagles.

The water — bright and clear — defies the name of the river it is becoming as it begins to flow out of the lakes.

But a closer look at the flat grasslands between the lakes and the mountains reveals dark hollows that scar the landscape. There used to be some 4,000 small, shallow lakes in the area. Now, three-quarters of them are dry.

River's Troubles Grow

In fact, the whole ecosystem at the river's source is in trouble, and scientists are worried. They say there hasn't been enough rain, and so the soil is increasingly dry and barren.

Rising temperatures associated with climate change are melting the glaciers and also thawing the permafrost, so water is being absorbed into the soil and not reaching the river, scientists say.

And Tibetan nomads who have roamed these parts for centuries have overgrazed the grasslands with their animals, according to the scientists, leading to severe soil erosion that also diminishes the flow of water to the river.

End of Nomadic Way of Life

Focusing on this last issue, the government has started to force the Tibetans to give up herding and their nomadic way of life — and to settle in one place.

A two-hour drive from the Yellow River's source are a few small, one-road towns that are reminiscent of the old American West. Music blares from the speakers of motorbikes driven by young Tibetans, who have traded in their steeds for mechanical horsepower.

Here, the government has built new housing blocks for nomadic families who have sold their animals.

Danma, 72, and his family are recent arrivals. He and his wife were both born in yurts. Neither one speaks Chinese — only Tibetan. The family received both a house and a stipend from the government in return for giving up herding.

Frail and slightly deaf in both ears, Danma says he is sad about the move, but he understands the reasons.

"It's very simple," he says. "The grasslands have changed. There is no grass, no water. So all we can do is sell our animals, which makes our hearts very heavy. It's all because the natural conditions have changed."

Tibetans' Future Uncertain

The family boils salty milk tea on the stove and listens to Tibetan music. In one room of the house, they have set up a Buddhist shrine with photos of the Dalai Lama prominently displayed.

Danma's son Pema Oser and his nephew Dorje Osel are both monks, and both men are studies in the contradictions brought on by the new way of life. They wear robes, but they also carry cell phones, which ring often.

Dorje Osel notes that the traditional ways are being eroded, just like the land itself.

"I have no idea what future the holds," he says. "We have no water and no grass. In 20 years' time, there won't be many animals left, and there won't be many nomads either."

The government says the settling of the Tibetan nomads is a necessary step in saving the river. Locals don't deny it, but there is also a feeling high on the plateau that this move to save the river is destroying an ancient way of life.

This story was produced for broadcast by NPR's Andrea Hsu.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))