As China's influence steadily expands around the globe, the country faces the public relations challenge of ensuring that the rest of the world sees it in a favorable light. China hopes to accomplish this goal through the use of "soft power" by exporting its culture.

One facet of China's effort to win support centers on the ancient philosopher Confucius, who has become something of a Chinese brand. The country has opened hundreds of schools worldwide bearing his name to teach Chinese culture and language.

Essence of National Culture

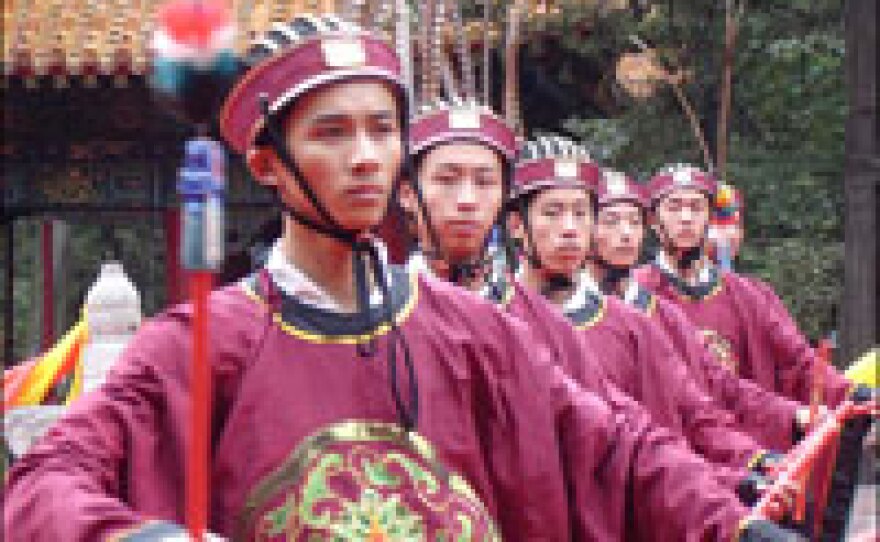

Every year, Chinese officials and family members gather in front of the grand halls and ancient cypress trees of Confucius' home to celebrate his birth, now 2,558 years ago. Attendants in embroidered robes perform ritual prostrations, and students recite Confucian texts.

During the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, Confucian statues and books were smashed and burned. Today, however, Confucius is once again a source of national pride.

"Even if Chinese people haven't entirely understood Confucianism, it has been a part of their entire system of thought for thousands of years," Kong Deyong, a 77th-generation descendant of the philosopher, says as he drives to the ceremony. "That's why we say it's the essence of our national culture."

Confucianism was at the heart of what made China the soft-power powerhouse of Asia for centuries. China was mostly unable to physically conquer its neighbors — Japan, Korea and Vietnam. But these nations willingly adopted Confucian culture, as well as Chinese forms of government, art and literature.

Now, China is using the philosopher's name on the more than 200 "Confucius Institutes" it has opened since 2002 in about 60 countries.

Soft Power

In 2006, President Hu Jintao visited a Confucius Institute in Nairobi, Kenya, and sang along with its first graduating class.

Afterward, one of the Kenyan students asked Hu, "Did we sing well?"

"Yes, you did," Hu replied. "That folk song is from my hometown. You sang it well and with Chinese flavor."

The girl told him she wished to come to China to study and work, and Hu said she would be welcome.

The exchange was shown on Chinese state television, making the message clear: Foreigners are respectful of China and its culture.

But China is careful to point out that the Confucius Institutes aren't pushing any ideological agenda.

"Confucius Institutes do not teach Confucianism. They don't promote any particular values," says Zhao Guocheng, an Education Ministry official in charge of the institutes. "They're just an introduction to Chinese culture, and they're established at the invitation of foreign people who want to understand China."

In a major speech last year, however, Hu pointed to soft power as a national goal for the first time. "We must enhance culture as part of the soft power of our country to better guarantee the people's basic cultural rights and interests," he said.

Exporting Values

The ultimate soft-power competition is sports, and China is betting that hosting the Beijing Olympics this summer will be an unprecedented opportunity to wow the world.

From athletes and police to volunteers and taxi drivers, the capital's residents are practicing putting their best foot forward.

In Beijing's suburbs, a school for airline attendants is training the young women who will present medals at the Olympics. Dressed in matching red uniforms, they balance English textbooks on their heads for good posture and clench chopsticks between their teeth to get their smiles just right.

One trainee, Cao Xiuting, sees the whole thing as a great opportunity.

"It will give me an opportunity to improve myself and my sense of service. And as a Chinese, I'd like to use my smile to show our foreign friends that we are a nation of etiquette," she says.

Of course, China has had success exporting some parts of its culture without any effort on Beijing's part — like Kung Fu movies, basketball star Yao Ming or mushu pork.

But Ge Jianxiong, a historian at Shanghai's Fudan University, points out that exporting values is harder than exporting, say, mushu pork, because there isn't really that much difference among nations' values.

"Some here say, 'Since ancient times, the Chinese people have been industrious, brave and caring towards the old and the young.' I ask them, 'What nation on earth is not brave, industrious and caring towards the old and young?'" he says.

In official propaganda, China's leaders espouse a harmonious society, at home and abroad.

Critics call this an awkward and unconvincing shibboleth. China's leadership developed the "harmonious society" idea, they say, to paper over the simmering unrest in Chinese society caused by autocratic government, corruption and a yawning gap between rich and poor.

"What kind of ideas and values will China promote to get the world's support?" asks Ding Xueliang, a researcher with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. "China is poor in this respect. It's not that Chinese are stupid or lack the potential. It's that its government propaganda system is incapable of producing concepts that are attractive to societies with freedom of expression."

A 'Beijing Consensus'?

Opinion polls suggest that China's public image has recently taken a bruising, particularly in the West. A February poll by Gallup showed that 55 percent of Americans have an unfavorable opinion of China, compared with 42 percent who have a favorable one. Last year, the two groups were roughly even.

The situation is different in Asia, where Gallup found a median of 46 percent of respondents approved of China's leadership, compared with 34 percent approval of U.S. leadership.

Some people also say that China's rapid economic growth is a model worth emulating, but Ding disagrees.

"All you have to do is to look at the cost. It's extremely high," he says. "The reason there are all these social protests and all this pollution is because economic growth is the sole objective, while the costs have been ignored."

Some pundits talk of a "Beijing consensus" — a combination of economic reform, pragmatic diplomacy and undemocratic government — to be emulated by other countries. But Beijing itself hasn't backed this idea.

Wu Jianmin, president of China's Foreign Affairs University, says the formula makes him uncomfortable.

"We're still trying to find our own way. To speak of a Beijing consensus or a Washington consensus is too simplistic. There may be some good aspects to Beijing's way, but they may only be suited to China's situation," he says.

A Confucian rule says, "Don't do unto others what you wouldn't wish upon yourself." Confucius' message on soft power was clear: Lead by moral authority, not force. Keep your own house in order, and others will follow your example.

Whether China's leaders have learned these lessons remains to be seen.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))