Clapping solemnly, dignitaries in Norway celebrated this year's Nobel Peace Prize winner, imprisoned Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo -- with an empty chair -- as Beijing blocked broadcasts of the ceremony in China.

Friday's presentation marked the first time in 74 years that the award was not handed over. Liu wasn't able to collect the prestigious $1.4 million award in Oslo because he is being held in a Chinese prison.

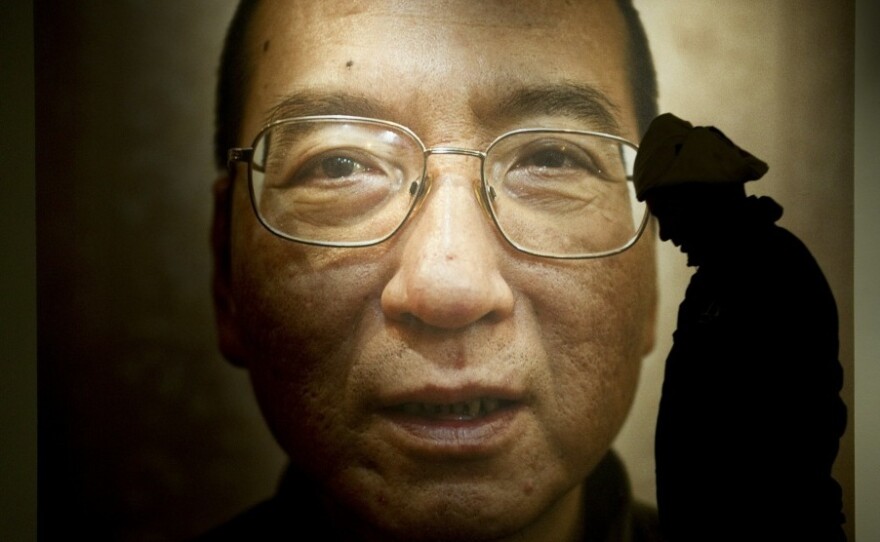

The 54-year-old writer and democracy activist (his name is pronounced LEE-o SHAo-boh) is serving an 11-year prison sentence on subversion charges for urging sweeping changes to Beijing's one-party communist political system. His wife is under house arrest.

The award to Liu infuriated Beijing, which sees it as an attack on China's political and legal system. Both CNN and BBC TV went black at 8 p.m. local time, exactly when the ceremony was taking place.

Some 1,000 guests, including ambassadors, royalty and other VIPs took their seats in Oslo's modernist City Hall for the two-hour ceremony, among them U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and U.S. Ambassador Barry White. About 100 Chinese dissidents in exile and some activists from Hong Kong were also attending.

Chinese dissident Wan Yanhai, the only one on a list of 140 activists in China invited by Liu's wife to attend the ceremony, said the jubilation felt by many at Liu's honor will be tinged with sadness.

"I believe many people will cry, because everything he has done did not do any harm to the country and the people in the world. He just fulfilled his responsibility," Wan told The Associated Press. "But he suffered a lot of pain for his speeches, journals and advocacy of rights."

Training A Lens On China

But there's nothing like a Nobel Peace Prize to focus the world's attention on human-rights abuses The award represents an ongoing public relations headache for China over its human-rights record, while potentially turning Liu into a symbol with likely resonance well beyond this week's events.

The Nobel citation calls Liu the "foremost symbol" of the human-rights struggle in China. By giving him the prize -- Liu was named the winner in October -- the Norwegian Nobel Committee made its own words come true, focusing international attention on his case and potentially elevating him to a status akin to 1991 Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi of Myanmar.

Suu Kyi's release from house arrest last month leaves Liu as the sole Nobel Peace Prize winner currently serving time in prison. He becomes the first winner not to be allowed to collect his award since Nazi Germany precluded pacifist Carl von Ossietzky from going in 1935.

China clearly does not want to be lumped in with such oppressive regimes as Myanmar and Nazi Germany. Yet its handling of Liu's award demonstrates some awkwardness for the country as it continues to grow into its role as a major world power, says Stewart M. Patrick, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

"For those fighting for change in China, the award becomes a symbol of the fact that although China has brought huge economic gains to its population -- probably the greatest poverty alleviation in world history -- it still has a long way to go when it comes to exercising fundamental human rights," Patrick says.

The country detained hundreds of other dissidents and warned other countries of potential repercussions if they sent representatives to the ceremony in Norway. China also blocked access to the websites of the BBC, Norway's NRK and other news organizations ahead of the ceremony.

Liu In Context

Before being selected for the Nobel Peace Prize, Liu was not especially well-known.

Liu took part in a hunger strike during the 1989 pro-democracy protests in Beijing's Tiananmen Square. Liu has dedicated his award to his fellow protesters.

Two years ago, Liu helped write "Charter 08," a document calling for freedom of speech and the press. "We must abolish the special privilege of one party to monopolize power and must guarantee principles of free and fair competition among political parties," the document states.

Liu was sentenced to prison for 11 years last December on subversion charges.

The award has brought him greater fame -- within China, as well as on the international scene.

"The Chinese people are going to be interested about what got Mr. Liu locked up -- his writings and particularly Charter 08," says Phelim Kine, an Asia researcher for Human Rights Watch. "Over time, against the government's wishes, Mr. Liu, within China, will have an increasingly high profile."

Kine predicts that Liu's writings "are going to go viral." That remains to be seen. China has kept close control of political discourse on the Internet, through its so-called Great Firewall.

"The Chinese have reacted very harshly to this award," notes Bonnie Glaser, an expert on Chinese foreign and security policy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. "What they care about primarily is the implications domestically. They don't want to hear the Chinese people commenting favorably in the blogosphere or on Twitter about Liu Xiaobo."

Another Dalai Lama?

Glaser is skeptical that Liu will be able to achieve enough lasting prominence and importance within China to be a threat to its regime. But it's clear that the Nobel -- and China's response -- have brought Liu and the Chinese dissident movement to greater prominence on the international stage.

At one time, the Nobel Peace Prize was generally granted to people who helped put an end to specific wars. In recent decades, its reach has been broader, honoring individuals and organizations in such areas as human rights and even the environment.

The question looking ahead is whether Liu's status as a Nobel laureate will continue to grant him a continuing platform as a powerful symbol, as had been the case for earlier dissidents such as Lech Walesa of Poland and Andrei Sakharov of the old Soviet Union.

Over the years, China has sought -- without great success -- to isolate the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet, who was awarded the prize in 1989.

Foreign leaders visiting China will now frequently, if not inevitably, be asked questions about Liu by their own traveling press corps.

"China really craves soft power -- respect for what the country stands for," says Kine, the Human Rights Watch researcher. "For the Chinese government, this is and will continue to be a running sore."

Attempting Coercive Diplomacy

But the prominent role of cash-flush China in the global economy has, so far, made it seemingly immune to the pressures of international public opinion.

"The possibility exists that Liu could become somebody that is seen by various interest groups around the world for advancing human rights in China," says Glaser, the CSIS scholar.

"But I think the Chinese government will work very hard to prevent that from happening," she continues. "There is already considerable pressure being put on companies, not just from Norway, who are actively supporting the award to Liu Xiaobo."

China continues to call Liu a criminal, and its Foreign Ministry spokesman said any country who sent representatives to the ceremony in Oslo were "clowns."

Beijing put pressure on foreign diplomats to avoid the ceremony. China and some 18 other countries -- including Russia, Iran, Venezuela and Cuba -- declined to attend.

At least 45 of 65 embassies in Oslo accepted invitations.

"My sense is that the Chinese are coming off as extraordinarily heavy-handed and that their effort at trying to extract promises from countries that they actually won't send participants to Oslo is really counterproductive in terms of their global image," says Patrick, who served a six-month stint as a researcher with the Nobel Peace Committee in 1993.

"It illustrates so starkly that the Chinese government is, frankly, afraid of their own people," he says, "as opposed to being a responsible global power that can stand a little internal criticism of its policies."

Material from The Associated Press was used in this report.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))