A community of US expatriates is forming in Tijuana . They are one minute who moved to join their reported partners to keep their families together. Many are still working in the US so we are sending their children to school here so the have the content with lengthy border wait times. Because of their deported husbands there denied access to century a trusted program that allows quicker border crossings. Jean Guerrero has the story. She is used to waiting hours at the border crossing but for her three children it is torture. The family lives part-time in North Senegal County. When her husband was deported to Mexico 12 years ago they considered moving everyone to did Juana. The oldest son has autism. He does not speak Spanish. He has difficulty in learning. He will be able to make it out there. She says she -- he hates saying goodbye to his father every time. I miss him so much. It makes me so sad. She applied for the traveler program. The border agent told her she did not qualify because she was married to a deported man leaving her high risk. I got emotional and I started to cry. I said if it is the issue where you think I will cross him through SENTRI it will not happen. Cement shoes that she would not risk jail time because her children depend on her. They declined to comment. Immigration lawyer was the agency regularly tonight SENTRI . Eventually having US government punishing these families twice. Directly denied it because of concerns they will try to smuggle their husbands across the border. She says these are people who would most benefit from SENTRI . I know women that have developed anxiety problems. One woman is a Lisa Lopez that works for the health center and lives in Tijuana with her children in a Mexican father. She is a primary breadwinner in her family. She says about her recent five-hour wait at the border. Try to pass the time by flipping through radio station after radio station. I have breakdowns and I had an anxiety attack. District that off it took a few hours. It did linger. She said she is afraid of losing her job. She also applied for the SENTRI travel program. They told her they would never qualify package was married to deported man. I have no criminal record and I have nothing on my driving record. I have a great employment history. Humorously drove back to Tijuana. Which is here I feel good. The house feels different. I have my kids. He was deported month after marrying Bridget or go he since become a pastor. It was a challenge and at the same time I was sure it was a challenge to overcome. If I believe in God, I knew I would 60s. He says of the hardest part is not being able to play in active role in his children's lives. I've never had the happiness of taking my son to school. I missed it. She plans to reapply for SENTRI . That story from Jean Guerrero. Welcome. How did you find out about the situation concerning the denial of SENTRI passes to the wives of deported men? The immigration lawyer who I interviewed for the story contacted me about this and she had been monitoring Facebook groups that these women use. The woman I interviewed for the story they used Facebook groups and posted as well as many other woman have posted about being tonight SENTRI because of their deported husbands. Utah's about three women affected by this triggered you know how many people are in the same boat? Four I to have any official figures but South of the border sisters have more than four hundred members echoed not all of them are wives of deported Mexicans. The our US and Canadian women who moved to Mexico. Of both of them are wives. Tell us about the border patrol's rationale in denying the passes to the spouses of deported Mexican nationals? Is it because cars with SENTRI passes are not searched? Four exactly. People with SENTRI passes get to the border quickly because they are not searched. The regular borderlines but officials will ask many questions sometimes the question will ask upwards of a minute and a will often searching vehicles. The century -- Is the legality of this this kind of denial based on what your spouse did is that being challenged legally or is this really solely within the discretion of the US custom and for protection? Perfect there is no litigation that I'm aware of. It appears to be -- the denial typically occurs during the in person interview with official. If you look at the customs and border protection sort of guidelines as to why they would deny century -- San Ysidro 2 people. Some reasons are very specific like if you been convicted of any criminal offense or have criminal charges or if you're the subject of an investigation by any federal state or local law enforcement agency but there is also one bullet point in their that is kind of a. It says you could be denied SENTRI if you cannot satisfy the agency of your low-risk status or meet other program requirements. That appears to be the sort of point that's preventing this women. How much does having a SENTRI pass change your border wait time? Mac very significantly. Depending on the time of day SENTRI line might have no wait time at all or up to 20 or 30 minutes. The regular lines rarely take under an hour especially during rush hour. It is often stuck for hours. One women in your feature report makes this trip basically every day. Exactly. She is a primary breadwinner in her family as many of the US women I spoke to. She gets up at like 5 AM to get to work at 9:00. Is or any record of a wife of a deported spouse using a SENTRI pass to smuggle her husband back into the US? Four i don't know any specific cases but that doesn't mean it has not happen or been tried. There have been many reported attempts to SENTRI since it was started. I just don't know the details of whether or not they were wives of deported Mexicans. More than 200,000 people have SENTRI and to want to. So some people listening to this might say why don't the wives of these deported man just find jobs in Mexico. One of the women I spoke to to do that. She is in the web story and she works as a teacher in a English-language school in Tijuana and earns a closet of about $7000 a year, which is barely enough to make ends meet. She would apply for a job in San Diego but can't justify it. She feels it would mean too much time away from her kids in the morning and she would have to Rebecca earlier so that she could wake up much earlier. Of course if she had SENTRI that would be different. I've been speaking with Jean Guerrero. Thank you very much.

A community of US expatriates is forming in Tijuana . They are one minute who moved to join their reported partners to keep their families together. Many are still working in the US so we are sending their children to school here so the have the content with lengthy border wait times. Because of their deported husbands there denied access to century a trusted program that allows quicker border crossings. Jean Guerrero has the story. She is used to waiting hours at the border crossing but for her three children it is torture. The family lives part-time in North Senegal County. When her husband was deported to Mexico 12 years ago they considered moving everyone to did Juana. The oldest son has autism. He does not speak Spanish. He has difficulty in learning. He will be able to make it out there. She says she -- he hates saying goodbye to his father every time. I miss him so much. It makes me so sad. She applied for the traveler program. The border agent told her she did not qualify because she was married to a deported man leaving her high risk. I got emotional and I started to cry. I said if it is the issue where you think I will cross him through SENTRI it will not happen. Cement shoes that she would not risk jail time because her children depend on her. They declined to comment. Immigration lawyer was the agency regularly tonight SENTRI . Eventually having US government punishing these families twice. Directly denied it because of concerns they will try to smuggle their husbands across the border. She says these are people who would most benefit from SENTRI . I know women that have developed anxiety problems. One woman is a Lisa Lopez that works for the health center and lives in Tijuana with her children in a Mexican father. She is a primary breadwinner in her family. She says about her recent five-hour wait at the border. Try to pass the time by flipping through radio station after radio station. I have breakdowns and I had an anxiety attack. District that off it took a few hours. It did linger. She said she is afraid of losing her job. She also applied for the SENTRI travel program. They told her they would never qualify package was married to deported man. I have no criminal record and I have nothing on my driving record. I have a great employment history. Humorously drove back to Tijuana. Which is here I feel good. The house feels different. I have my kids. He was deported month after marrying Bridget or go he since become a pastor. It was a challenge and at the same time I was sure it was a challenge to overcome. If I believe in God, I knew I would 60s. He says of the hardest part is not being able to play in active role in his children's lives. I've never had the happiness of taking my son to school. I missed it. She plans to reapply for SENTRI . That story from Jean Guerrero. Welcome. How did you find out about the situation concerning the denial of SENTRI passes to the wives of deported men? The immigration lawyer who I interviewed for the story contacted me about this and she had been monitoring Facebook groups that these women use. The woman I interviewed for the story they used Facebook groups and posted as well as many other woman have posted about being tonight SENTRI because of their deported husbands. Utah's about three women affected by this triggered you know how many people are in the same boat? Four I to have any official figures but South of the border sisters have more than four hundred members echoed not all of them are wives of deported Mexicans. The our US and Canadian women who moved to Mexico. Of both of them are wives. Tell us about the border patrol's rationale in denying the passes to the spouses of deported Mexican nationals? Is it because cars with SENTRI passes are not searched? Four exactly. People with SENTRI passes get to the border quickly because they are not searched. The regular borderlines but officials will ask many questions sometimes the question will ask upwards of a minute and a will often searching vehicles. The century -- Is the legality of this this kind of denial based on what your spouse did is that being challenged legally or is this really solely within the discretion of the US custom and for protection? Perfect there is no litigation that I'm aware of. It appears to be -- the denial typically occurs during the in person interview with official. If you look at the customs and border protection sort of guidelines as to why they would deny century -- San Ysidro 2 people. Some reasons are very specific like if you been convicted of any criminal offense or have criminal charges or if you're the subject of an investigation by any federal state or local law enforcement agency but there is also one bullet point in their that is kind of a. It says you could be denied SENTRI if you cannot satisfy the agency of your low-risk status or meet other program requirements. That appears to be the sort of point that's preventing this women. How much does having a SENTRI pass change your border wait time? Mac very significantly. Depending on the time of day SENTRI line might have no wait time at all or up to 20 or 30 minutes. The regular lines rarely take under an hour especially during rush hour. It is often stuck for hours. One women in your feature report makes this trip basically every day. Exactly. She is a primary breadwinner in her family as many of the US women I spoke to. She gets up at like 5 AM to get to work at 9:00. Is or any record of a wife of a deported spouse using a SENTRI pass to smuggle her husband back into the US? Four i don't know any specific cases but that doesn't mean it has not happen or been tried. There have been many reported attempts to SENTRI since it was started. I just don't know the details of whether or not they were wives of deported Mexicans. More than 200,000 people have SENTRI and to want to. So some people listening to this might say why don't the wives of these deported man just find jobs in Mexico. One of the women I spoke to to do that. She is in the web story and she works as a teacher in a English-language school in Tijuana and earns a closet of about $7000 a year, which is barely enough to make ends meet. She would apply for a job in San Diego but can't justify it. She feels it would mean too much time away from her kids in the morning and she would have to Rebecca earlier so that she could wake up much earlier. Of course if she had SENTRI that would be different. I've been speaking with Jean Guerrero. Thank you very much.

A community of expatriates is forming in Tijuana: American women who moved south of the border to join their deported Mexican partners and keep their families together.

Many continue working in San Diego or sending their children to San Diego schools, and must contend with two- to four-hour wait times at the San Ysidro Port of Entry, the world's busiest land crossing.

These women report being denied access to SENTRI, or Secure Electronic Network for Travelers Rapid Inspection, a trusted U.S. Customs and Border Protection traveler program that allows expedited border crossings. They're told it's because they're married to deported men, making them possible human smugglers.

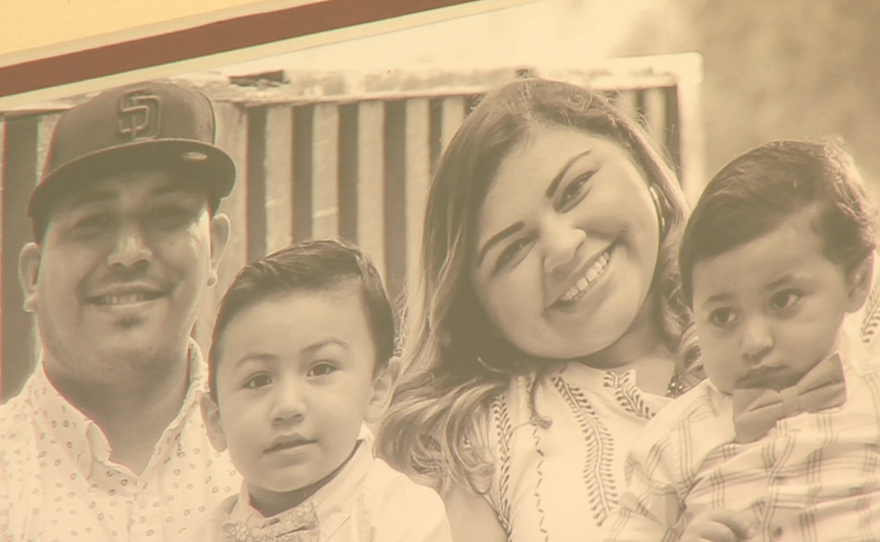

Bridget Bohorquez, 37, is one of those women. When her husband was deported from Chicago in 2004, she considered moving the whole family to Mexico. But her oldest of three children, Aaron, has autism. She felt she had to keep him in a U.S. school.

“He doesn’t speak Spanish,” Bohorquez said. “He has difficulty learning. He won’t be able to make it (in Mexico).”

Instead, the family decided to move near a port of entry and become cross-border residents. For most of the year, Bohorquez and her three children live in North County on weekdays and in Tijuana on weekends with her husband, Eduardo.

Crossing into the U.S. poses the same challenges every week. Nine-month-old Benjamin starts crying after a couple of hours. Bohorquez must pull over to breastfeed or change his diaper. Then the four-year-old girl, Hannah, sobs in boredom. Aaron, 14, stops playing his portable video games and tries to comfort the others.

Bohorquez applied for SENTRI in 2011, knowing that its vehicle and pedestrian lanes rarely exceed 30-minute wait times. During the interview, a U.S. Customs and Border Protection officer told Bohorquez she didn’t qualify because she was married to a deported man.

“I got emotional there, I did start to cry,” Bohorquez recalled. “I said, ‘Look, if it’s an issue where you think I’m going to cross him through SENTRI, that’s not going to happen. I know the risk, I’m not stupid. I have a child to think about.’”

U.S. Customs and Border Protection declined to comment on the eligibility of deportee spouses for SENTRI, but did say that one reason applicants may not qualify is if they “cannot satisfy (the agency) of their low-risk status.” The application process includes a comprehensive background check and an in-person interview.

"Punishing these families twice"

Immigration attorney Nicole Ramos said there is no policy barring spouses of deportees from SENTRI, but the agency regularly denies it to them in practice because of concerns they may try to smuggle their spouses across the border. “So essentially, you have the U.S. government punishing these families twice,” Ramos said.

Ramos said the wives of deported men are the people who could most benefit from SENTRI because of their cross-border lives. More than 90 percent of the people deported to Mexico are men, according to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement figures. Their wives are often the primary breadwinners in their families, paying for rent and their children’s food and education with their U.S. salaries.

The stress of what these women call “la línea,” Spanish for the line, takes a physical and emotional toll. “I know women that have developed back problems while sitting in line, women who have developed anxiety problems from sitting in line,” Ramos said.

SENTRI would allow them to cross the border in a fraction of the time since inspections at the customs booths in the dedicated lanes for trusted travelers are faster. More than 220,000 people were enrolled in SENTRI last year in the San Diego-Tijuana region, according to the Otay Mesa Chamber of Commerce.

"I had a breakdown"

Ilicia Lopez, 28, lives with her two sons and their Mexican father in Tijuana, working every weekday at the San Ysidro Health Center on the U.S. side of the border. She is her family’s primary breadwinner.

She gets up at 5 a.m. to get to work at 9 a.m., but is sometimes late. During the long standstills in the border crossing line, Lopez does her makeup. She flips through radio stations to distract herself from the stress of waiting. But she often fears losing her job due to tardiness. A recent border commute took nearly five hours.

“I had a breakdown. I had an anxiety attack,” Lopez said.

Lopez also applied for the SENTRI trusted traveler program. She said that during her interview, the border officer told her she would never qualify because she was married to a deported man at the time. She said he told her not to bother applying again.

“I have no criminal record. I have nothing on my driving record. A good employment history. Everything,” she said. “I have no understanding of why they would deny me.”

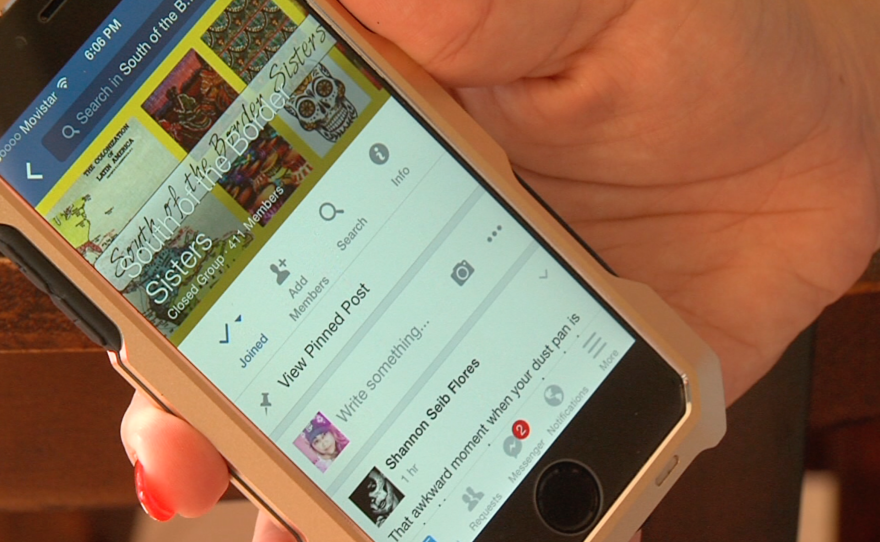

She and other women in her situation use Facebook groups like Cómo Está La Línea and South Of The Border Sisters to check wait times, vent about the line and bond about their shared experiences.

Lopez launched a petition calling the lengthy border wait times "inhumane," asking Customs and Border Protection to take additional measures to decrease them.

Labeled 'high risk' of human smuggling

Women like her are a small but growing sector of Mexico’s border population at a time when net migration from Mexico to the U.S. has sunk to near-historic lows. More people are moving from the U.S. to Mexico than vice versa. Between 2009 and 2014, about one million Mexicans and their families migrated from the U.S. to Mexico, while about 870,000 moved from Mexico to the U.S., according to the Pew Research Center.

The reversing flow has many causes, including an improving economy in Mexico. Deportations are another factor. Although U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement deportations plummeted to the lowest level in a decade last year at about 230,000, the Obama administration has deported about 2.5 million immigrants — more than any other president in U.S. history.

Their American spouses sometimes made the difficult decision to join them.

Testimonies indicate that these women are most often denied SENTRI during their in-person interviews with Customs and Border Protection officers. When Bohorquez and Lopez were told they were considered “high risk” for human smuggling, they asked if they could enroll without registering a vehicle, which is optional, so as to make use only of SENTRI’s pedestrian lanes — a more challenging place to smuggle their husbands. Both Bohorquez and Lopez were told no.

To cross back into the U.S., they use the Ready Lanes, reserved for travelers with radio frequency identification cards. But even those waits can last for hours during rush hour.

Rejecting 'la línea'

Another woman, Christina Lopez, applied for SENTRI in June. She said she was told she didn’t qualify because she had committed a crime by marrying a man who had once entered the U.S. illegally. Ramos, the immigration attorney, called the officer’s interpretation of law “erroneous.” Lopez said she has a clean record.

“Basically, (the officer) was like, 'The only thing standing between you and SENTRI is your husband,'” Lopez said.

She met her husband in Ohio. When his grandmother was dying in 2008, he traveled to Mexico to say goodbye to her. He tried to cross back into the U.S. through Arizona, and was picked up by Minutemen who handed him over to U.S. Border Patrol.

Lopez decided to move to Tijuana to be with him. The couple has two children. Lopez’s annual income — the equivalent of about $7,000 a year teaching at an English-language school in Tijuana — is just enough to sustain the family in Mexico. “I don’t look for a job in San Diego because I can’t justify the time it takes to cross every morning,” she said.

Working in San Diego would mean too much time away from her children, she said, because she would have to be absent in the mornings and go to bed hours earlier in preparation for “la línea.” If she had a SENTRI pass, Lopez would seek work in the U.S. She has a college degree in international relations and diplomacy.

"When She's Here, I Feel Good"

Bohorquez, the cross-border resident of Tijuana and North County, said she tries to stay optimistic about her situation. “We wanted to be a family, and if this is how our family can be together, then we’re going to make the best of it,” she said.

During the summer months, it’s easier. Bohorquez and her children stay in Tijuana with her husband, making occasional trips to the U.S. for health care and other needs. On a recent Monday, after a visit to North County for a doctor’s appointment, Bohorquez pulled into the driveway of her house in Tijuana, honking the horn of her Honda sports utility vehicle.

“Papi!” her 5-year-old daughter cried.

“Oh, he can’t hear you,” Bohorquez laughed.

Eduardo Bohorquez emerged from the house and opened the back door of the car to greet his giggling children. He kissed them all and carried the girl inside. In the house, they absorbed themselves in domestic routine. Aaron surfed the internet on his laptop, and Hannah scrolled through her iPad. Eduardo fed the baby, Benjamin, while Bridget made copies for a class she was teaching at a nearby church.

“When she’s here, I feel good. I feel a family. The house feels different. I have my kids,” Eduardo said.

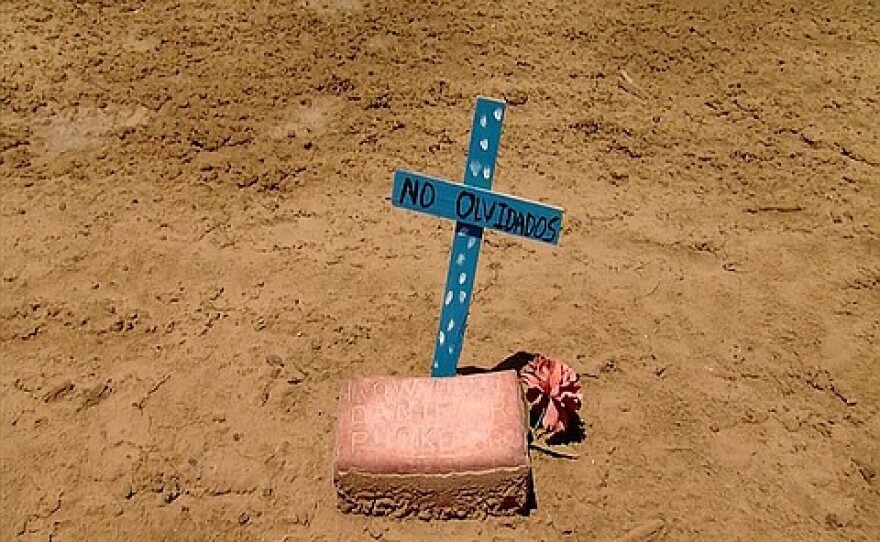

Months after their wedding, Eduardo was deported for a drug offense he had committed decades before as a young man. He had since become a pastor. The couple met at a church camp in Chicago.

“It was a challenge, and at the same time, I was sure it was a challenge I had to overcome. If I really believed in God, I was going to be able to succeed. Otherwise, my faith was not a real faith,” Eduardo said.

He continued preaching in cities throughout Mexico, and now gives sermons and classes at Asamblea Apostólica De La Fe En Cristo Jesus, a ministry in a low-income neighborhood of Tijuana.

The couple thinks if it weren’t for their faith, they wouldn’t have been able to make their cross-border lives work. When they feel despair, they turn to the Bible for wisdom.

“If God wasn’t the center of our lives, things would just collapse,” Bridget said.

“(Our faith) has sustained us, not just economically, but it has sustained our marriage and our children,” Eduardo agreed.

For him, the hardest part of their cross-border existence is not being able to play an active role in his children’s lives in the U.S.

“I’ve never had the happiness of taking my son to school,” Eduardo said. “All of that, I missed it. His friends don’t know me.”

Bridget plans to re-apply for SENTRI for herself and her children, despite the high cost — $122.25 per person — in case the next border agent sympathizes. Then, at least, the family could visit Eduardo more often.