Three former servants are suing a Kuwaiti diplomat, alleging that he treated them like slaves in his suburban home in Washington, D.C. The workers are poor women from India, and they say the diplomat worked them for more than 15 hours a day. They also claim his wife beat one of them repeatedly.

But even if the women can to prove their charges, they will have a difficult time winning their case: The Kuwaitis deny the accusations and say they have diplomatic immunity.

'They Would Beat Me'

The servants say they were rarely allowed to go outside. Neighbors say they didn't even know the women lived on their quiet street in suburban Washington for the first month after the women arrived.

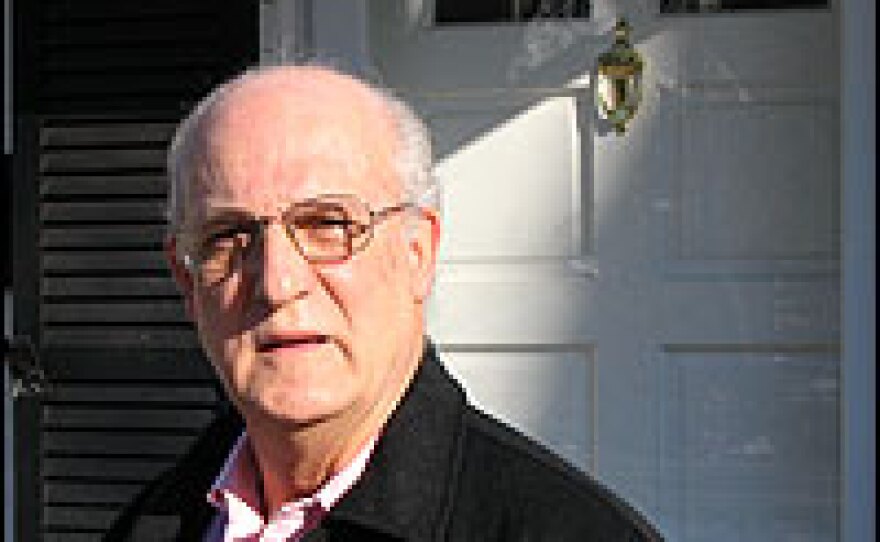

"I was washing my car here in my driveway, and one of them was pacing up and down the street, right in front of my driveway, looking at me with the fear of God in her face," says Hector Rodriguez, a neighbor who first spotted one of the women in the summer of 2005.

He crossed the street and asked the woman if she was in danger.

"And then she proceeded to explain the situation that she and her friends were in — that they were basically treated as slaves," he says.

Last month, the woman, Jaoquina Quadros, and her two co-workers sued their former employer, Major Waleed Al-Saleh, a Kuwaiti military attache. They say the diplomat brought them from Kuwait under false pretenses.

According to the suit, Al-Saleh seized their passports and told them not to look out of the windows or open the door to the house. The suit also alleges that Al-Saleh knocked one of the women, Kumari Sabbithi, unconscious.

"The day used to start around 6:30 or 7:00 a.m. and used to go to 11:30, 12 in the night," says Sabbithi. "My work included feeding the babies — three babies — in the morning, then again, helping cooking for the family, cleaning the kitchen, cleaning each and every room."

For all her work, Sabbithi says she earned $242 a month, which is less than 60 cents an hour. When she made mistakes, Sabbithi says that the diplomat's wife struck her in the head — once with a wooden box and another time with a package of frozen chicken.

"They would beat me with hands. They would push me against the wall," she says. "They would hold my head and drag me."

'Seeing Workers as Not Quite Human'

Al-Saleh declined an interview. But in statement, he called the accusations "absolutely untrue."

Sabbithi's story is not unique. Foreign diplomats have been accused of abusing domestic workers in the United States for years. Staff at Andolan — a South Asian workers' support group in New York — say they know of 25 similar complaints this decade. And back in 1996, the U.S. secretary of state complained to foreign embassies in Washington, D.C., about the confinement, overworking and underpaying of servants.

This particular case also provides a glimpse into a much larger problem in places such as the Persian Gulf and Malaysia.

In 2005, the State Department released a report that said foreign servants were treated so badly in Kuwait that 800 fled their employers and were living in shelters at any one time.

"The embassies of Indonesia and Sri Lanka in many countries have set up shelters on site, because every day, they receive dozens of complaints from women who haven't received their wages, who have been beaten by their employers, who have lost 20 or 30 pounds because they're not being given enough food," says Nisha Varia of Human Rights Watch. She has interviewed hundreds of such workers.

"So when I visit the Indonesian embassy in Riyadh, for example, there's 150 women in the embassy, because they have just fled abusive conditions," she says. "The treatment of these women is very much tied into gender discrimination, racial discrimination. All of these attitudes really play into employers seeing workers as not quite human."

Fleeing for Her Life

After several months working for the diplomat, Sabbithi was depressed and considering suicide. In October 2005, she confronted the Kuwaitis and complained that they owed her a month's salary.

Sabbithi says the diplomat's wife called her ungrateful and listed all of the good things the couple had provided for her.

"Madam says, 'I give you food. I give you soap. I give you everything, everything.' I said, 'Madam, give me my money,'" says Sabbithi.

She also recalls that the wife was so furious, she threatened to cut off her tongue.

Sabbithi says the diplomat later pushed her to the floor. The lawsuit alleges that she hit her head on a kitchen table and blacked out. When she came to, her co-workers urged her to flee for her life. Sabbithi feared she would never be able to return to India to see her husband and two young daughters.

She gathered a few belongings, including a Bible, and slipped out the front door while the family relaxed in the basement.

She started walking. But Sabbithi didn't know where to find Hector Rodriguez, the neighbor her co-worker had met a few months earlier.

"After passing three houses, I stood there in the cold and prayed: 'What should I do? Should I go forward, anyway, or should I go back to the house?'" Sabbithi says. "Then I decided, 'No, I'm not going back.'"

She came to a house with a light on, which turned out to be the home of Rodriguez.

Rodriguez recalls the moment: "I hear a nasty knock. My wife and I, we were stunned. Someone was trying to knock the door down. She only had a couple of plastic shopping bags. She was dressed in a summer maid's dress. Don't forget, it was very cold that night."

When he opened the door, Sabbithi barged in and introduced herself. Rodriguez called the police, who confronted the Kuwaitis. But the husband said they had diplomatic immunity.

Rodriguez understands the limits of the law, but he has trouble stomaching it.

"How is it possible that — in the country where freedom is relished — that these atrocities are allowed to happen under the umbrella of diplomatic immunity?" he asks.

Several months after Sabbithi left the house, her co-workers fled as well. Sabbithi knows she's unlikely to win her lawsuit, even with the help of her lawyer, who works for the American Civil Liberties Union. But she says she's just hoping for some measure of justice.

Currently, she works as a babysitter and says her new boss treats her well.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))