Demond Mullins spent a year in Iraq with the National Guard. When he came back, he felt alienated and angry at what he had seen and done in the war. Now Mullins has found a degree of peace in higher learning.

"Academia ... that's where I'm at," the City University of New York grad student says. "Right now, school, books — Weber, Marx, Durkheim — that's my medication."

That's his medication now. But if it's true that there are seven stages of grief, it's fair to say that Mullins is going through several stages of adjusting to his new life.

His military transport plane brought him back in the fall of 2005. When he arrived at New Jerseys' Fort Dix, there were no bands waiting to welcome him home, Mullins says.

What waited instead was a pair of white-painted school buses. Those buses would carry the surviving members of his National Guard unit back toward civilian life.

Mullins, who grew up in Brooklyn, spent a year as a clothing model. He was ambitious enough to join the National Guard to pay for college.

That was the life Iraq interrupted.

Ignoring the Awkward Questions

And when he tried to resume it, Mullins' old friends kept asking questions, like "What was it like when you shot someone?"

"I don't know," he says. "My experiences are not pornography for my friends or for anyone else. I use the word pornography because I feel like it is just the ... exploitation of my personal experiences for someone else's entertainment."

Mullins says he either ignored the question "or I would just say, 'You know, I don't want to talk about things like that' or just say, 'I didn't shoot anybody or whatever.'"

'Stressed Out and on the Edge'

He says he's not sure if he did shoot and kill anybody, though he knows exactly what he did at close range.

"I dehumanized people," Mullins says. "I don't even know how many raids I did while I was there. But during raids you're throwing them up against the wall, you're tying their hands behind their back, you're dragging them out of the bed. You're dehumanizing them in front of their wives and their kids and, you know, the women are crying and the children are crying and you're just like, whatever. Put a bag over their head or blindfold, drag them into the Humvee.

"Certain exhibitions of violence on my part that were probably unnecessary — were definitely unnecessary. But I was really stressed out and on edge at the time and I conducted myself ... like that."

When he returned from Iraq, Mullins says he felt angry at himself. He broke up with his girlfriend. He spent days in his apartment.

"Staring at the wall. Not eating. I lost about 15 to 20 pounds," he says. "My friends still look at me and like, 'What happened to you?'"

Mullins says he was depressed to the point of being suicidal. Two of his friends have died since their return from Iraq, including one who shot himself in the face, Mullins says.

"To me, that would be the only way that I was capable of doing it because it was fast and it was a tool that I was very familiar with," he says.

Mullins got counseling from the Department of Veterans Affairs. He didn't like it and didn't want to take medication.

He managed to resume college, get a degree and move on to graduate school.

Speaking Out Against the War

Along the way, Mullins focused his anger. He spoke out against the war at marches and rallies.

He appeared in an anti-war documentary called The Ground Truth.

"When I first started anti-war activism, it was because I felt guilty," Mullins says. "Because I'd meet people, especially a lot of civilians on the street, and they say, 'Oh, thank you for your service. Thank you for protecting America.' Like, what are you talking about? I wasn't protecting America. I was protecting myself and my buddy, you know?"

After Mullins participated in the film, he felt less of a need to speak out.

And by this semester at graduate school, most of his fellow students and at least one of his professors had no idea of his background.

"I had no idea he was a veteran," says sociology professor John Torpey. "It's just not something you would have ever known. He seemed a little sheepish about people knowing it."

Learning and Understanding

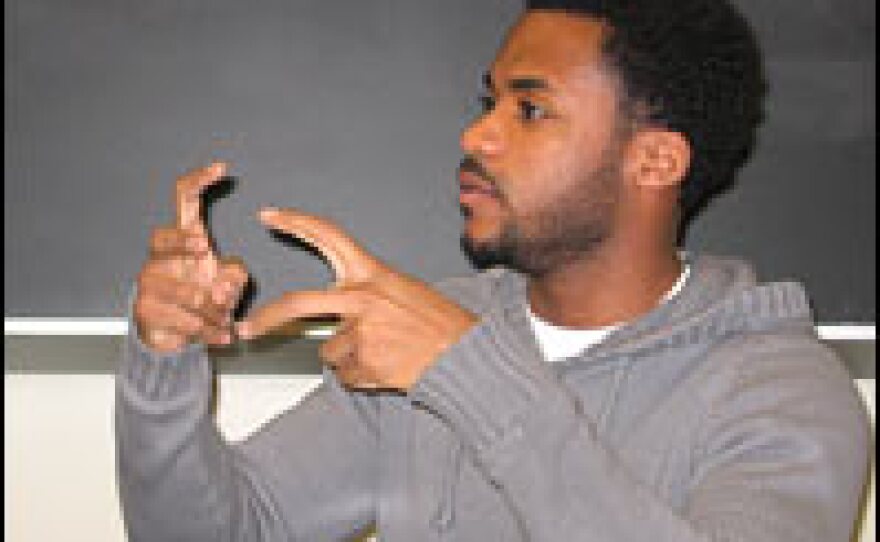

Mullins, who knows so much about war from personal experience, comes to class and speaks about social and political theories of war. Recently, he was leading a class discussion — learning by teaching.

Mullins says he can apply the principles he's learning to the situations he experienced in Iraq.

"I can understand the chaos that is society, the chaos that is life through a theory," he says. "In some way, I look at my experiences in Iraq and I can understand them through theory."

Mullins says he has gone through degrees of change since the documentary was filmed.

"When I came back from Iraq, I was just like, anti-war, anti-establishment and anti-myself," he says. "But it's time for me to move more in the direction of where my interests are going."

Is he feeling less alienated?

"I'm feeling more like I'm understanding this country, this society. And I don't want to scream against it. Right now, I'd just like to study it."

There was a time when Mullins was screaming against his own life. For now, at least, he seems to be studying that, too.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))