The professed mastermind of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, is expected to arrive in New York for trial by the end of the year. But it won't be his first trip to America. He has been here before, as a college student in the early 1980s.

Mohammed's first real taste of America came at a small two-year Baptist school called Chowan College in 1983. Nestled among the cotton fields of Murfreesboro, N.C., Mohammed arrived hoping his time at Chowan would become a springboard to an American education.

Back in the 1980s, all Chowan students — and that would have included Khalid Sheikh Mohammed — were obliged to study Christianity extensively. That meant prayers, singing and biblical instruction in addition to regular classes. It was an odd requirement for the son of an imam who had been a member of an Islamic group, Muslim Brotherhood, since he was 16.

Dr. Garth Faile was Mohammed's freshman chemistry teacher. He's a soft-spoken man from Alabama who has been teaching at Chowan for nearly 40 years. Faile, wearing a tie that shows the elements in the periodic table, pulls out an old blue grade book and finds his former student.

"Let's see, there he is right there," he says, pointing to a name in the first column. "Mohammad, Khalid. It is spelled differently there."

'Like Anyone Else'

Back in the 1980s there were lots of Middle Eastern students attending Chowan. The dean of admissions was behind that, Faile said. He apparently shipped school brochures out to U.S. embassies all over the Middle East to recruit foreign students. And it worked. "See how many names begin with an A as you go down the group there," Faile says, reading the class roster. It began with Ahmed, Abu, Abdullah and continued to names like Smith.

Of the 54 students in Khalid Sheikh Mohammed's class, 29 were from the Middle East.

Chowan didn't require prospective students to take an English proficiency exam, which made it attractive. It meant that foreign students arrived, took a lot of math and chemistry and tried to improve their English. Once they accomplished that, they would move on to other schools.

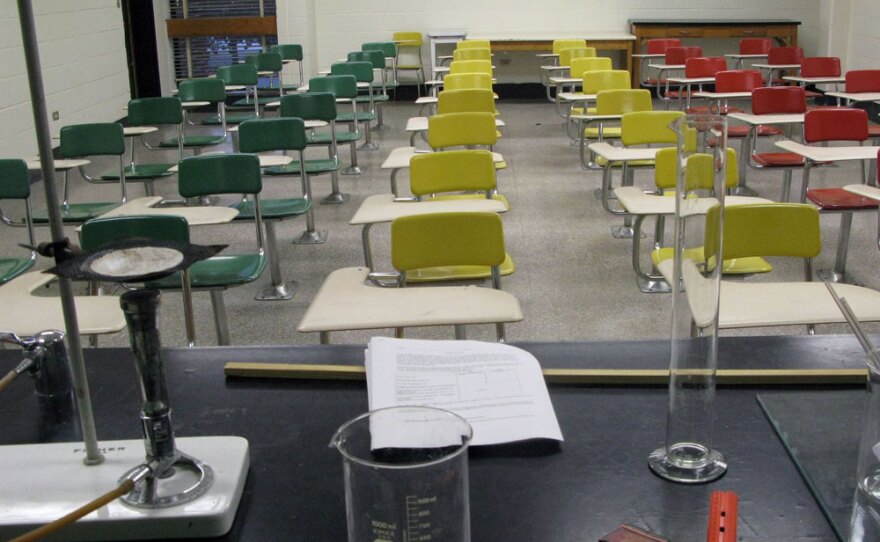

Faile has taught chemistry in the same classroom for almost 40 years. It is stark and white but for the eight rows of desks all bolted to the floor. The professor walks about halfway down the first row and puts his hand on the chair. "He sat about here," he said, of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. Aside from remembering where he sat, Faile says there was nothing that stood out about Mohammed — though he did earn one of one highest grades in the class.

"What he had in mind then, as opposed to now, I don't know," Faile says. "There was no reason for him to become a radical or to kill people. We treated him and the Middle Eastern students like anyone else."

Which, of course, touches on one of the great mysteries about Khalid Sheikh Mohammed: How could someone who seemed so ordinary become the man who allegedly planned the Sept. 11 attacks?

A&T Days

After just a semester at Chowan, Mohammed thought his English was good enough to move on. So he transferred to North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro. It's Rev. Jesse Jackson's alma mater. And it's where Mohammed began studying mechanical engineering.

When he wasn't in class, Mohammed appeared to spend his college years in a kind of self-imposed isolation — about five miles off campus on a residential, tree-lined street. He and the other Middle Eastern students rented several apartments and turned one into a mosque, according to Sammy Zitawi, a friend of Mohammed's at the time.

"They will just go there and get together and do the prayer and between prayers, if you have a homework problem, they help each other in studying and all this," said Zitawi, who was also Mohammed's mechanical engineering lab partner. "They stayed with friends they could blend with."

Friends they could "blend with" consisted of devout Muslims who avoided the kinds of things you come to expect in college.

"They wouldn't listen to music, they wouldn't play music," says Zitawi. "He wouldn't take a picture back then because they thought it was against religion."

While the young men around Mohammed lived in a world apart, it wasn't an austere existence. Every Friday and Saturday night Mohammed and the other Middle Eastern students used to get together for dinner. There would be prayers, homework and then little skits or a play. The men called it "The Friday Tonight Show."

Zitawi, who is a now a small businessman in Greensboro, says his friend, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, was one of the stars. "This guy was funny, he could make you laugh," he said. "He could make fun out of anything."

Zitawi said the disheveled, balding Khalid Sheikh Mohammed who was photographed right after his capture in Pakistan looked nothing like what he remembered. The Khalid Sheikh Mohammed he knew was a small man, just 5-foot-4 and maybe 135 pounds. "He had a cute face with a beard. He had a long hair back then. That's why I didn't know him when he had less hair and no beard. They were talking Khalid Mohammed, I knew him as Khalid Sheikh."

Negative Experiences In America?

As much as he tried, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed couldn't wall himself off from America completely. In the summer of 1984, he was involved in a car accident. He had been driving with an expired license and was taken to the local jail in Greensboro.

The ceilings in the jail where Mohammed was held are low. The bars on the cells have been painted so often, they look thick. The inmates wear orange and red jumpsuits and leg irons.

Zitawi said his friends at A&T were hauled off to jail all the time. "There are so many reasons for them to take you downtown," he says. "For any reason they take you downtown."

Back then, Zitawi says the Middle Eastern students at A&T had the unfortunate tendency to view traffic laws as strictly optional. In fact, he says even he spent some time in jail — for speeding. "I felt like an animal being there," Zitawi says. "They lock you behind cages. I was so scared. Never again. It will never happen again. It gave me a good lesson."

Zitawi learned a lesson, but what did Khalid Sheikh Mohammed draw from his time in America? The conventional wisdom has long been that the best way to get people overseas to like the U.S. is to have them experience it for themselves. And yet, a recently released CIA report claims "Khalid Sheikh Mohammed's limited and negative experiences in the United States — including a short stay in jail — almost certainly helped propel him on his path to become a terrorist."

But the truth is, it seems that Mohammed never really experienced America. He kept himself apart and then found what he wanted to find. And it appeared Mohammed couldn't get out of America fast enough. He finished his engineering degree in two-and-a-half years.

Then he went Afghanistan — where he joined the mujahedeen.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))