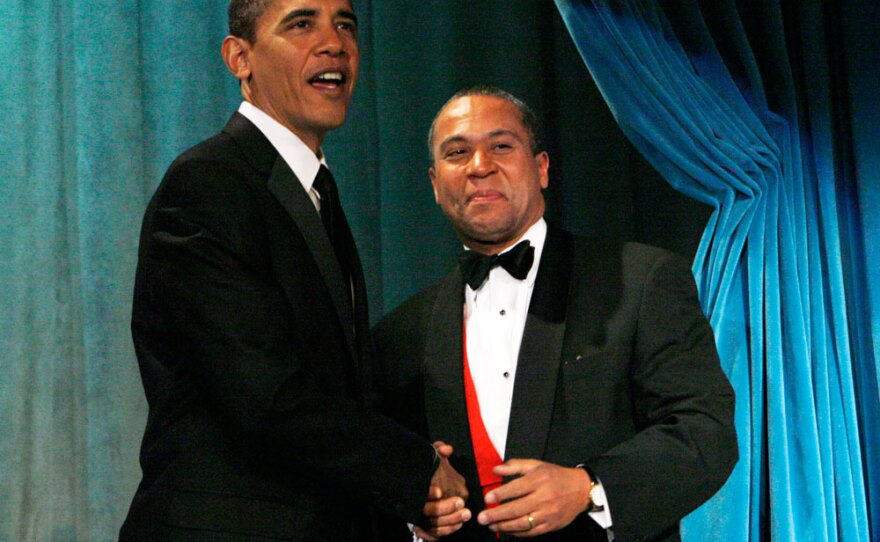

From President Obama to prominent mayors and legislators across the country, a new wave of "post-black leaders" has been gaining prominence, in part by avoiding the identity politics of their predecessors.

But that inclusive outlook has translated into a painful reality for many in the black community who feel that a historic opportunity to address urban issues is slipping away, a victim to the changing political landscape, shifting demographics and a dreadful economy.

It was against that backdrop that members of the restive Congressional Black Caucus met privately Thursday with the president, who invited them to the White House to talk about his finish-line push to get health care legislation passed.

The leaders emerged from the one-hour meeting pledging to work together on an agenda that includes health care, education and the economy. But the nation's first black president no doubt got a private message from caucus members who are increasingly frustrated by what they see as Obama's lack of focus on poverty and unemployment in the African-American community.

'No Such Thing As A Black President'

Obama wanted to come in as a new kind of politician, and, with the others, wanted to posture as de-racialized politicians. But they need to understand that it still matters.

The caucus' complaints — publicly aired before the meeting — underscore the shifting reality for traditional African-American leaders in a world where their most prominent political descendants are stepping away from identity politics.

It's not that America is suddenly post-racial, says Manning Marable, director of Columbia University's Institute for Research in African-American Studies.

"But there's just no such thing as a black president," says Marable, the author of many books on race and black leaders in America. "Obama's base is multiracial and multiclass and a reflection of the reality of America."

He characterizes new black leaders, from Obama to Massachusetts Democratic Gov. Deval Patrick, as "post-black" politicians who "rarely, if ever, privilege or emphasize race in political decision-making."

The transformation, he argues, has been necessary and inevitable.

'They Need To Understand That [Race] Still Matters'

Obama's election epitomized the rise of the new class of African-American leaders that included not only Patrick, but also high-profile mayors Cory Booker of Newark, N.J., and Adrian Fenty of Washington, D.C.

But as prominent movement leaders leave the stage because of age or, in the case of longtime New York Congressman Charlie Rangel, age and scandal, some African-Americans say they feel abandoned by the new wave.

"When I look at Patrick, Booker and Obama, they are not traditional black politicians — they're not from the black community and they don't have a natural base," says Leonard Moore, author of Carl B. Stokes and the Rise of Black Political Power.

"Obama wanted to come in as a new kind of politician, and, with the others, wanted to posture as de-racialized politicians," says Moore, an assistant vice president at the University of Texas at Austin. "But they need to understand that it still matters."

There is frustration that the president hasn't specifically articulated black issues, Moore says, particularly the pressing problems of the urban African-American community.

Unemployment among African-Americans has been hovering around 16 percent; the overall national rate reported earlier this month was 9.7 percent. A new jobs bill, black caucus members have complained, does little to address that stark reality.

So frustration is understandable, say activists like Kristen Clarke, a civil rights lawyer for the NAACP's Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

"Certainly, Obama's election reflects the transformative possibilities for black American leadership," Clarke says.

"But there remains a need for a very deep conversation about race — and it needs to happen at the executive branch, with civil rights group on the ground and in the communities," she says.

Marable argues that social advocacy is better pursued outside of electoral policy, with the end product sometimes translating into legislation.

Change Isn't Coming; It's Here, And It's Latino

The intense discussion about leadership in the black community comes at a time when the political influence story is also shifting.

The nation will embark on a new census in coming weeks, and numbers collected during the once-a-decade effort will be used to fashion congressional districts.

Census experts predict that more minority-dominated districts will emerge from the process, but they will largely be majority Latino, says Tim Storey, a redistricting expert and senior fellow at the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Two decades ago, following the implementation of the Voting Rights Act, there was a surge in African-American candidates and members of state legislatures, he says.

Those numbers appear to have hit a plateau. Last year, there were 628 blacks among the nation's 7,382 state legislators. Blacks make up 13 percent of the nation's population and 9 percent of its state legislators.

"Really, the census story is going to be more on the Hispanic side, rather than the African-American side," Storey says. Growth in the Hispanic community, expected to become the nation's majority in 30 years, is far outpacing black population growth.

Going forward, the only way to increase black political representation, Storey says, will be to get African-American candidates elected in more white or multirace districts. It will be all about building coalitions.

Data show that about one-third of all black state legislators serving over the past few years had been elected in majority-white districts.

Hard Truths

That's the future, experts say, and one that Obama and other new-wave black politicians recognize.

Only 10 to 15 percent of whites now say they won't vote for a candidate who is black, Marable says, a dramatic change from the days when African-American candidates were typically unable to muster more than 40 percent of the vote.

Race remains a fundamental factor affecting one's chances in life, he says, but it has had a rapidly declining effect on electoral politics.

"Symbolic representation that may have worked in the '60s and '70s doesn't work today," Marable says, calling outdated the old desire to simply have what was referred to as a "black face in a high place."

Next week marks the second anniversary of then-candidate Obama's historic speech on race in America, "A More Perfect Union."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))