The Compassionate Friends is often described as the type of organization that nobody really wants to belong to. But more than 1,200 people are expected to attend the group's annual convention over the July 4 weekend.

Though the name sounds innocuous, The Compassionate Friends is a lifeline for grieving parents and other relatives. It's a network of support groups for those whose children have died.

Losing a child is not like other losses of loved ones. Folded into the death of a child is the death of the future -- your child's future, that you have dreamed of and nurtured, and your own future, including the pride of parenthood, the possibilities of grandparenthood and the excruciating knowledge that all your child's potential has been destroyed.

Eventually, as life moves on, the pain can actually deepen for the bereaved parents. Friends and family expect them to be moving on, to be getting better, to be healing. But for many people, losing a child just doesn't work like that. The spirit of the child is still vital in the broken hearts of the parents. And the parents struggle constantly to stay connected to the child and to keep the child's memory alive in their strange, new, childless world.

At a Compassionate Friends meeting, parents are not only allowed to brag and tell stories about their dead children as if they were still alive -- they are encouraged to do so.

The organization "won't take away your pain. And it won't bring your child back," says Chuck Collins, a national board member of Compassionate Friends. "You know there is nothing that can do those two things. All it can really do is to help you learn ... how to live life, having suffered this terrible tragedy. And find a way to still have purpose in your life."

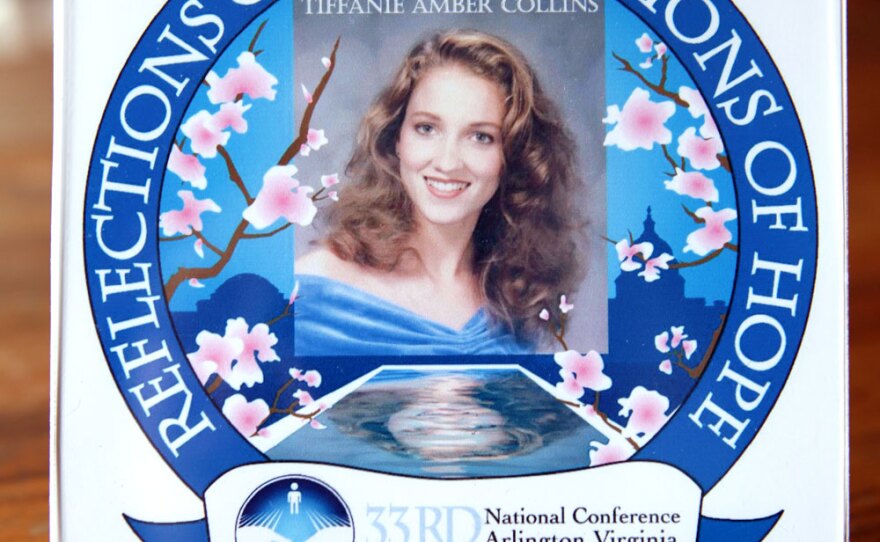

Chuck and his wife, Kathy, lost their oldest child, Tiffanie, in 1996, when she was a student at Clemson University. Shortly after Tiffanie's death, Chuck and Kathy became active in their local Northern Virginia chapter of Compassionate Friends. They became chapter leaders, then regional coordinators. This summer they will be running the national convention in Arlington, Va.

Taught To Suck It Up

Chuck Collins is friendly-eyed and bearded, and his voice is surprisingly soft for a man who was a Washington, D.C., cop for 25 years. After retiring from the police force, he became an attorney. He took off a year or so to write a book about losing Tiffanie, Holding Onto Love: Searching for Hope When a Child Dies. He published it himself. All proceeds go to The Compassionate Friends.

Chuck says he first heard about Compassionate Friends when Tiffanie died but didn't want to take part. "I knew Kathy really needed to go," Chuck recalls during an interview at the couple's home in Fairfax, Va. "But I had been a cop for 25 years and we weren't big on sharing our feelings and emotions. We were kind of taught to suck it up. You know, if we were in pain, or we had any kind of emotion, that we try not to show it. So for me it was difficult to consider going to what I thought was a 'support group.' "

About three weeks after Tiffanie's funeral, Chuck and Kathy decided to attend a Compassionate Friends gathering. "It was really tough," Chuck says. "We went to that first meeting and I even put the car in reverse and was going to back out of the parking lot. Some chapter leader that was there got me and tapped on the window and said, 'Are you here for the meeting?' So I was stuck. I had to go in."

He points to Kathy. "I was looking for something that could help her. But in the process it turned out to be something that could help me."

"It's too devastating to ever expect you to ever get over the loss of a child who you cherish and love," Chuck says. "Regardless of whether they are 3 days old. Or 48 years old. They are still your child and it goes against the natural order of life that they should die before their parents. This group helps you immensely."

'People Get Nervous When You Cry'

The Compassionate Friends was founded in 1969 in Coventry, England, by a young hospital chaplain, Simon Stephens. He brought together two couples who had recently lost children. The parents -- who felt alone and even ostracized in a society built for the living -- discovered a shared depth of grief, understanding and empathy. They spoke the same language of loss. They realized that in their meeting, they felt less alone.

Eventually, they invited other bereaved parents to gather with them to talk about the variegated sorrows of losing children. Today Compassionate Friends has more than 600 chapters in the United States and scores of others in Canada, Great Britain and other countries. There are no annual dues and local meetings are free. The group operates on donations.

The only rule for belonging is that you must have lost a child, a grandchild or a sibling.

This year's convention -- registration fee for adults is $85 -- will feature more than 100 workshops, mostly for parents. There will be seminars for couples who have lost all of their children. And forums for bereft grandparents and siblings. There will be a candlelighting service and a memorial walk.

When people go to the conference, Chuck Collins says, "they can say what they want." They don't have to pretend that they haven't lost a child, he says, which is what most people have to pretend in their daily lives.

People who have lost children tend to "shut that side of their life down," he says, "because it may make them cry. And people get nervous when you cry."

For someone like Lynn Rhoads of Vienna, Va., who lost her only child, her son, Brent, in a 1994 highway crash, attending the national convention a year later proved to be a defining moment. "I had difficulty coping with the loss. I had no coping skills for that kind of loss and could not figure out what to do," she says.

A friend persuaded Rhoads to attend the national convention. "I wasn’t so sure about going," she says. But "I decided to go to the conference for just a while on the first day and that would be the end of it because I didn't think that was the forum for me and it wouldn't be all that helpful. My idea of staying a little while turned into going every day and staying until the very end each day."

At the conference, Rhoads says, "the workshops were helpful and provided answers to questions I had or information to think about. I met people in different stages of grieving and people who had made the journey through their grief and survived. From this, I got the strength and courage I needed to continue my journey."

She adds: "I also came to understand that what I was going through was normal for the situation I was in."

But The Compassionate Friends is not for everybody. Ellen O'Brien, for instance, is not a joiner. She lost one of her two sons, Griffen, in 2006. He was a student at Drexel University. He died of sudden cardiac arrest.

"I do find comfort in knowing others who share a similar grief," Ellen says. "There is a sad basic knowledge of our frame of reference. However, I have never been much of a formal group person."

Ellen scoped out The Compassionate Friends on their Web site but never did contact the group or attend a meeting. "What works best for me is reaching out individually," she says, "and keeping in touch in a less formalized structure."

Tiffanie's Display Case

In the foyer of Chuck and Kathy Collins' home stands a tall glass-and-wood display case. The shelves are packed with memorabilia from Tiffanie's brief but full life -- photos, trophies, a dance-team jacket she wore on a trip to Paris, a safety patrol badge. Here and there, artistic representations of angels and butterflies.

Visitors react to the display case in various ways, Chuck says. "Some people are very interested and will ask questions about it. Some people will look at it for what it is and say they are sorry. And some people will look at it and never say a word."

He says, "You get a mixture of reactions. But we always feel good because regardless, she's being remembered."

Chuck and Kathy both wear angel pins on their collars to honor Tiffanie. Chuck touches his pin with two fingers. "I kind of lie in wait for some poor unsuspecting person," he says. "I would be surrounded in court by lawyers. They would glance over at it. And it's got a little green stone, which was her birthstone, so they'd think it had something to do with Knights of Columbus or the Emerald Society. They'd say, 'What is that?' By the time I got done with them, they'd be grabbing for their briefcase, looking for an escape route."

He would take the opportunity, any opportunity, to pull out pictures of Tiffanie and tell stories about her. "I really started wearing mine because I was worried people were forgetting her. And I didn't want people to forget her."

There is no good way for a child to die. Tiffanie Collins had just come home from her sophomore year in college. She had been suffering with a sore throat for a few days. She was admitted to the hospital on a Saturday morning. She died at 6 p.m. Monday of bacterial meningitis.

"It's one of those diseases you can pick up at a college dorm if you haven't had the vaccine and back in those days no one told us about vaccines. It was a terrible experience," Chuck says. "A gut-wrenching ordeal."

A Lot Of Unanswered Questions

For Chuck and Kathy, the world fell apart.

Kathy recalls that in the first few weeks following the tragedy, she was swept up in funeral plans and surrounded by grieving family members and friends. There were many tears, many hugs. People would talk about Tiffanie a lot, Kathy says, "which was good. But, you know, as time goes on, people go on with their lives. You're left to still go on grieving. Some people still were around. But you have to learn to move on without them and deal with it yourselves."

Bereaved parents also have many unanswered questions. Some are cosmic, such as "Why did this happen to my child?" And "Why did this happen to me?"

But they also have many practical questions about how to go on living. "They're the kind of questions that may seem mundane and very trivial to somebody who's not in this kind of pain," Chuck says. "But if you're suffering that kind of devastation and anguish, questions like: 'Should I keep the door to my child's room open or closed?' can be huge."

They kept the door to Tiffanie's room closed.

"We always signed a greeting card with everybody's name on it. And now all of a sudden my daughter was gone. And I wanted to know: What do I do now?" Chuck says. Eventually, after hearing people at The Compassionate Friends talking about several different options, Chuck and Kathy chose to sign their greeting cards "The Collins Family."

And there is the inevitable awkwardness of how to answer the everyday question: Do you have any children? "When you're not expecting that question," Chuck says, "and you've suffered that kind of loss, it can knock you over."

So, Kathy is asked, how do you reply to that question? "We usually answer we have three children and one's in heaven. Or three children: David, Christopher and Tiffanie is in heaven. And then you either get someone who makes an about-face and walks the other way. Or sometimes someone will say, 'Well what happened to her?' "

Kathy and Chuck then seize the opportunity they long for, and eagerly talk about Tiffanie.

Editor's note: NPR national correspondent Linton Weeks and his wife, Jan, lost their only two children, their sons, Stone and Holt, in a highway crash in July 2009. In memoriam, they created The Stone and Holt Weeks Foundation.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))